Songs on the Death of Children

KINDERTOTENLIEDER: MAHLER, BEREAVEMENT, AND CONSOLATION

Michael Ignatieff

Posted by kind permission of Michael Ignatieff, writer, historian, professor and politician.

From Michael Ignatieff, On Consolation: Finding Solace in Dark Times (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 2021) pp. 167-181

I. INTRODUCTION

In 1804, in Vienna, a twenty-three-year-old pianist named Dorothea von Ertmann lost her only child, a three-year-old boy, after a short illness. By her own account, she fell into a deep depression. People visited her and tried to comfort her, to no avail. She was a young woman from a wellborn family who had arrived with her husband and infant child in Vienna two years before and, thanks to her playing in private salons, had made the acquaintance of Ludwig van Beethoven. When he heard of her grief, Beethoven visited her at home, sat down at the piano, and said, according to Felix Mendelssohn’s later account, that they would now talk to each other in the language of music. Beethoven improvised for an hour, during which Dorothea began to weep for the first time. When he finished, he stood up, pressed Dorothea’s hand, and without saying another word departed. Dorothea recorded her own feelings in a letter shortly afterward: Who could describe this music! I believed I was hearing angelic choirs, celebrating the entrance of my poor child into the world of light.

Ludwig van Beethoven | Getty/Unsplash | Dorothea von Ertmann

Sacred music—chorales, hymns, oratorios, masses—have consoled grieving men and women for millennia. Here, a purely secular occasion—a man improvising on a piano—assumed the role once performed by religious music and ritual. Two musicians trusted to the language of music, rather than sacred words or scripture, to conjure that world of light into being. When retold by Mendelssohn and romantic composers in the nineteenth century, this became a story about music’s new purpose in a secular world. The musicians who came after Beethoven had to measure up to the ambitions that he had given to music in a world turning away from the promise of heaven.

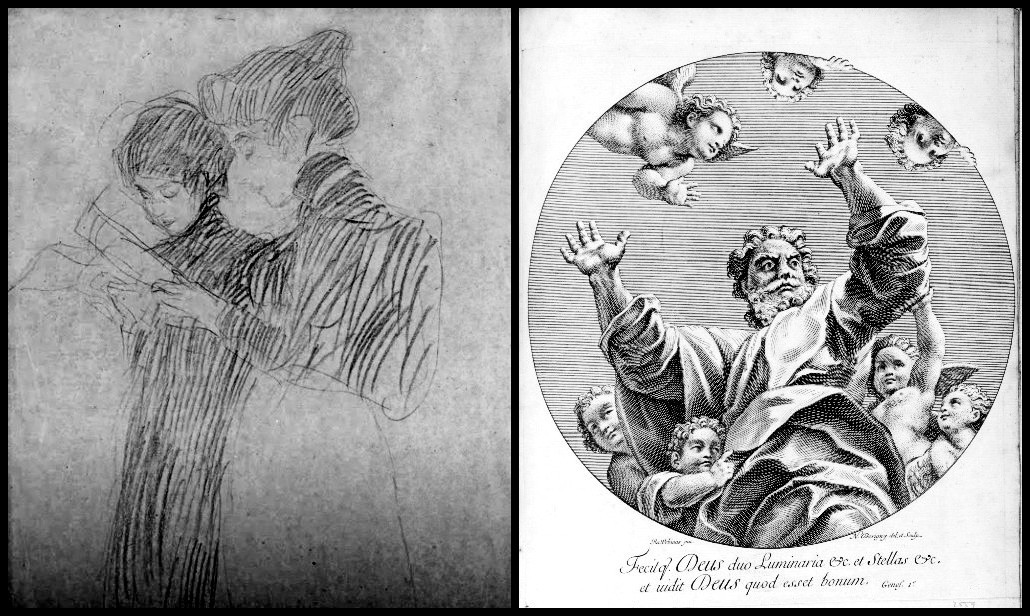

Gustav Klimt, Study for ‘Schubert at the Piano’, 1898 | Raphael, God Creating Heaven, 1695

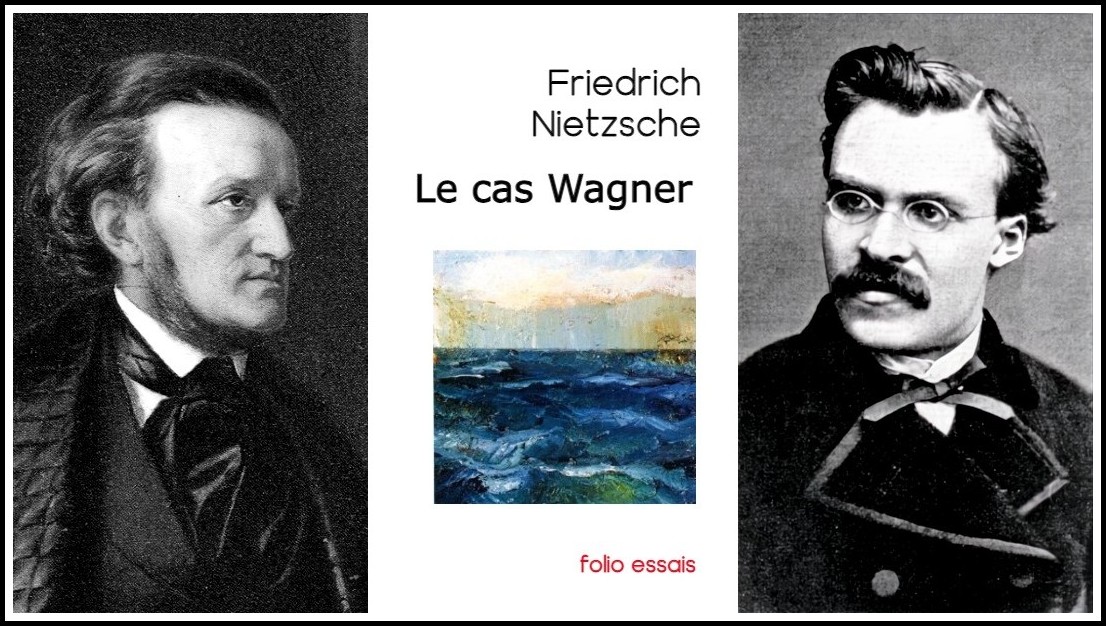

This transformation of music had been underway for some time. Handel’s Messiah—which opens with the soaring lines of his setting of the words of the prophet Isaiah—’Comfort ye, my people’—took the Christian message of consolation and performed it, not in a church, but in a Dublin auditorium in 1744 as a benefit concert for retired musicians and singers. Mozart’s Requiem, written in 1791 but left unfinished at his death, was first performed after he died at a benefit concert for his wife. After Beethoven, Verdi and Brahms composed requiems but used them to give utterance to secular griefs and had them performed in concert halls. In the case of Brahms’s Requiem, the cause for grief was the death of his mother; in Verdi’s Requiem, it was the death of his friend the writer Alessandro Manzoni. Dvořák, a devout Catholic, stayed closer to the sacred. His Stabat Mater of 1876 mourned the deaths of two of his children. In Wagner’s Parsifal, the composer disregarded traditional religious forms altogether and transformed the Christian story of suffering and redemption into a modern spectacle, performed not in a religious setting but at the Bayreuth Festival Hall. Parsifal disgusted Wagner’s former acolyte and admirer Friedrich Nietzsche, who insisted, furiously, that by setting the Christian language of consolation to music, Wagner had capitulated to Christianity’s ‘slave morality’ and its resentment-filled resignation in the face of human suffering. The only consolation entitled to respect, Nietzsche once said, was to believe that no consolation was possible.

Richard Wagner | The Case of Wagner | Friedrich Nietzsche

II. GUSTAV MAHLER

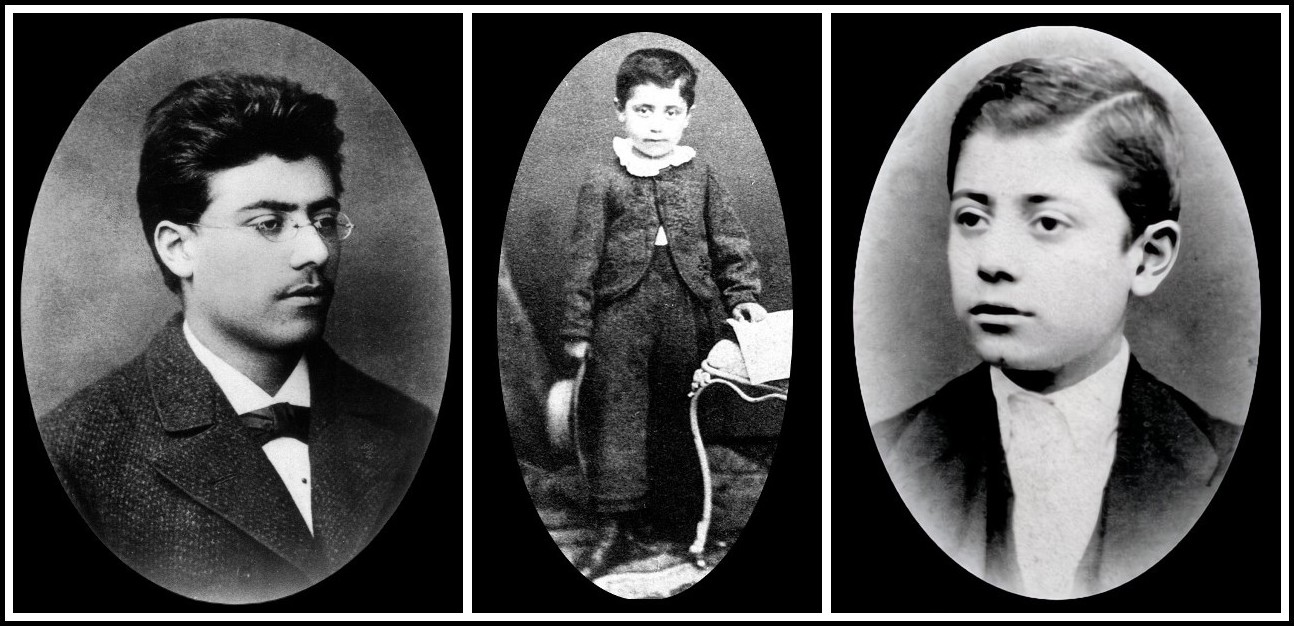

The figure who inherited and then transformed this debate about the relation between music and consolation was the son of a Jewish innkeeper in Iglau, a small town in Moravia in the Czech lands. At fifteen he had escaped from an unhappy family life—his father was an irascible tyrant, his mother lame, constantly pregnant, and victimized by her husband—to make his future as a music student in Vienna. Arriving in the capital city of the empire, he poured into music all the ambitions of an outsider: a provincial, a Jew, and a poor boy from an oppressive family. To these yearnings to escape, Gustav Mahler added the mighty ambitions for music that his generation inherited from his forebears.

Gustav Mahler at 18 (1878), 5-6 (1865) and 10 (1870-71) years of age

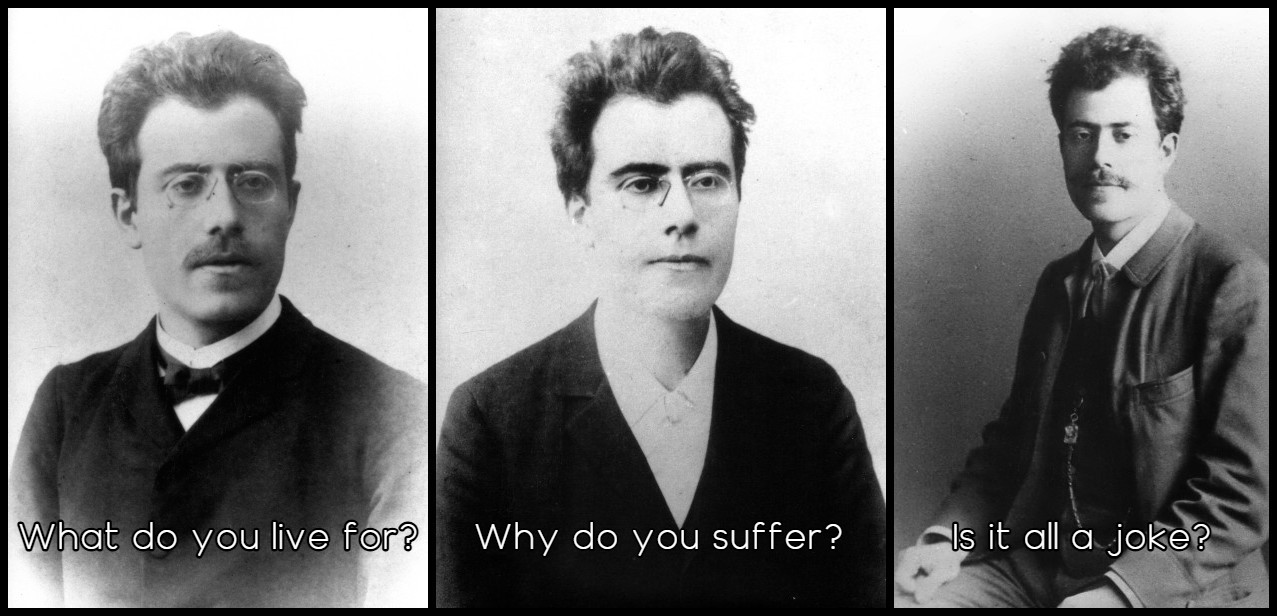

Mahler shared Wagner’s conviction that music should attempt nothing less than to provide meaning for men and women living after the death of the gods. They both sought to develop a musical form that would provide an experience of the transcendental and sublime. ‘Music must always contain a yearning,’ Mahler told an admiring female friend, ‘a yearning for what is beyond the things of this world.’ Mahler, like Wagner, dared to demand of his music that it provide answers to questions as old as Job’s. In one of his letters, he wrote: What do you live for? Why do you suffer? Is it all one vast terrifying joke? We have to answer these questions if we are to go on living.

Gustav Mahler: Budapest 1890 | Budapest 1888 | Prague 1885

He combined this yearning for metaphysical consolation with an uncanny realism, a capacity to compose music that brought to life sharp, disjointed fragments of memory from the world of his unhappy childhood. In his First Symphony, Vienna audiences of the time were baffled to hear the lilting, swaying sound of a children’s song—’Frère Jacques’—shattered by the careering horns of a village band. Later audiences have heard these moments as enactment of scenes from his childhood, when the coffin that held one of his brothers was carried past the open doorway of his father’s tavern and raucous noise blared heartlessly from within. Eight brothers and sisters died in infancy, and when Ernst, the youngest, who had revered Gustav, took ill in the spring of 1875, Gustav was at his bedside distracting him by inventing tall tales. After Ernst died, Gustav left Iglau. He returned only to recite kaddish beside the grave of his father.

Marie Mahler (mother) | Otto Mahler (brother-suicide) | Bernard Mahler (father)

He kept in his memory a primal scene from age five or six, when he had rushed out of the family tavern to get away from his father’s shouts and his mother’s tears, only to run into a village organ-grinder in the street outside, playing the old Viennese song ‘Ach du lieber Augustin.’ He described this scene to Sigmund Freud in August 1910, while they paced up and down the canals of Leiden. He had come to ask Freud for advice about the crisis in his marriage. Remembering this childhood scene, he told Freud, made him understand how, when he composed, he could not help interrupting passages of elevated sorrow with sudden notes of discordant and raucous levity. It was as if he could not keep the organ-grinders or village bands of his childhood from bursting into the concert hall. This was why, he told Freud, Viennese audiences had never liked his music. Later audiences heard this feature as precisely what was new: Mahler’s fusion of deeply personal and autobiographical impulses with grand, transformative, essentially religious ambitions.

Ken Russell, Mahler, 1974 | Gary Rich as Young Gustav

Witness to a primal scene: ‘During his presence in the Grünfeld household the boy was witness to a rape scene, which filled him with a horror that was to remain with him for decades. La Grange, however, says that Mahler merely witnessed sexual intercourse, which, misunderstanding the woman’s reactions, he mistook for rape.’ Egon Gartenberg, Mahler: The Man and His Music (New York: Schirmer Books, 1978) p. 7

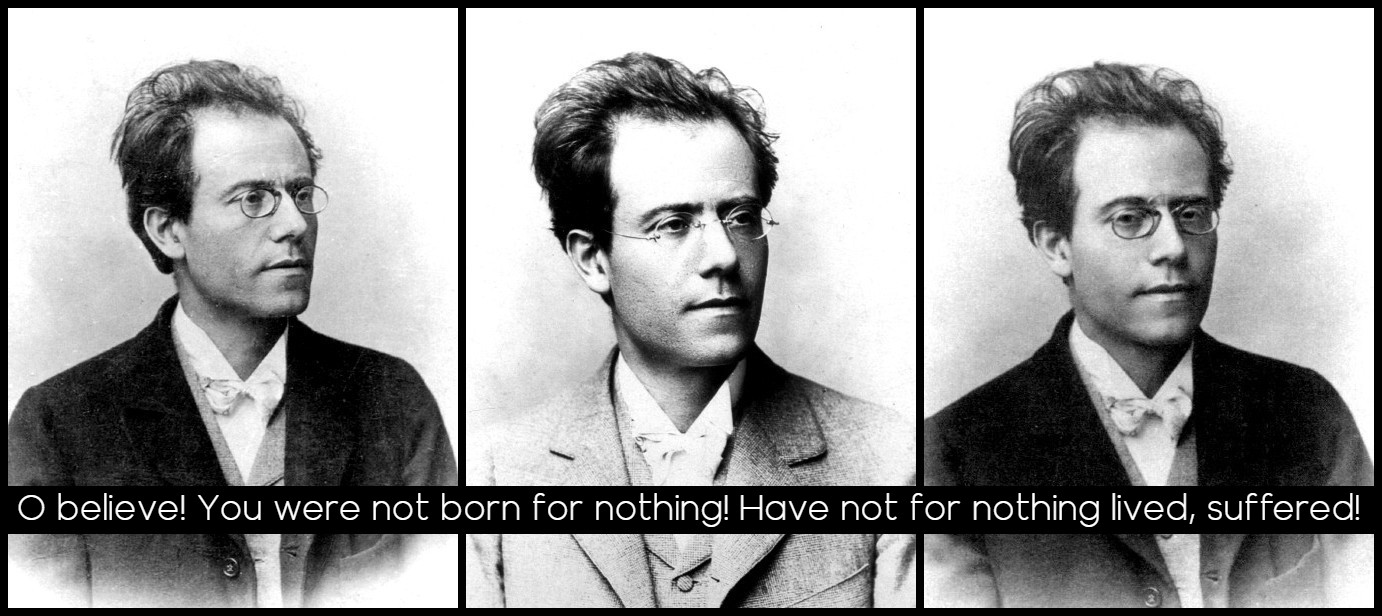

His Second Symphony, for example, written in the late 1890s, re-created Mahler’s own recurrent experience of psychic despair and recovery. The music is on a vast scale, but its impact is intimate and personal. Mahler achieved this effect by combining words and music in a symphonic form that placed dramatic orchestral effects at the service of the solitary intensity of the human voice. Mahler wrote lyrics of his own for the mezzo-soprano to express his recurrent struggles to believe in himself and his vocation: O glaube / Du wardst nicht umsonst geboren! / Hast nicht umsonst gelebt, gelitten! / O believe! / You were not born for nothing! / Have not for nothing lived, suffered!

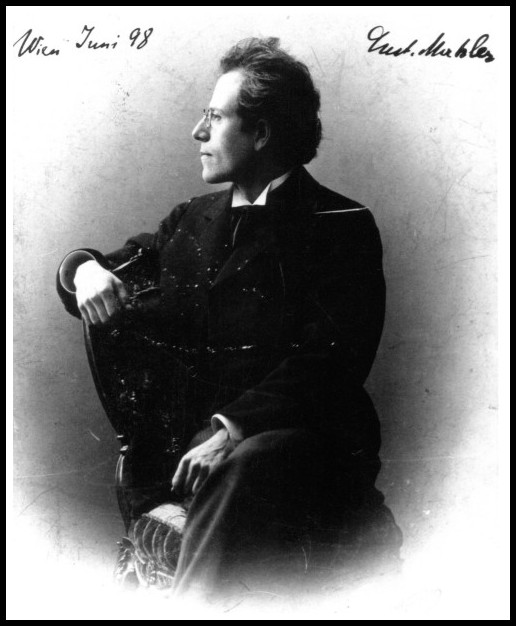

Gustav Mahler, Vienna, 1898

In seeking to express the innermost struggles of the psyche, Mahler’s music committed itself to transform the ancient liturgical ambitions of music—exultation, reverence, and consolation—for a listening public who now lived these experiences as private dramas of their interior lives. Mahler’s music may have retained essentially religious ambitions, but his view of actual religious doctrine, especially the Christian vision of paradise, was ironic and mocking. He was a Jew, after all, who was not allowed to ignore his Jewishness either, since Jews had long been barred from key posts in Viennese cultural life. In order to secure his post as director of the Vienna opera, he had converted to Catholicism, but it had been an instrumental move to further a career, never a conversion of the heart, and his sense of apartness and exclusion as a Jew never disappeared.

Mahler, Director of the Vienna Opera, 1898

His most extended treatment of the Christian paradise was in his Fourth Symphony, composed in an ecstatic burst of creativity by a Carinthian lake in the summer of 1901. In the last movement, he set to music ‘The Heavenly Life,’ one of the poems he had found in the collection of traditional folk verse, Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Boy’s Marvelous Horn), compiled in 1809 by Clemens Brentano and Achim von Arnim—two members of Goethe’s circle in Weimar. ‘The Heavenly Life’ is a vision of paradise straight out of Brueghel, seen from the wide-eyed and innocent perspective of a peasant boy, an alternatively cheerful and casually brutal story of saints in heaven carving up little lambs for the saved souls to eat: John lets the lambkin out / And Herod the Butcher lies in wait for it. / We lead a patient and innocent dear little lamb to its death. / Saint Luke slaughters the oxen without any thought or concern. / Wine doesn’t cost a penny in the heavenly cells; / The angels bake the bread. Mahler wrote comic and tender music to convey the sheer incongruity of these peasant visions of plenty, side by side with saints engaged in blithe animal slaughter. His music ends by conveying, in the summer afternoon stillness that falls toward the end, a clear-eyed view that this peasant paradise is an imagined artifact of another time, beyond the reach of the present.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Peasant Wedding, 1568 | Von Hans Schliessmann, Mahler Conducting, 1901

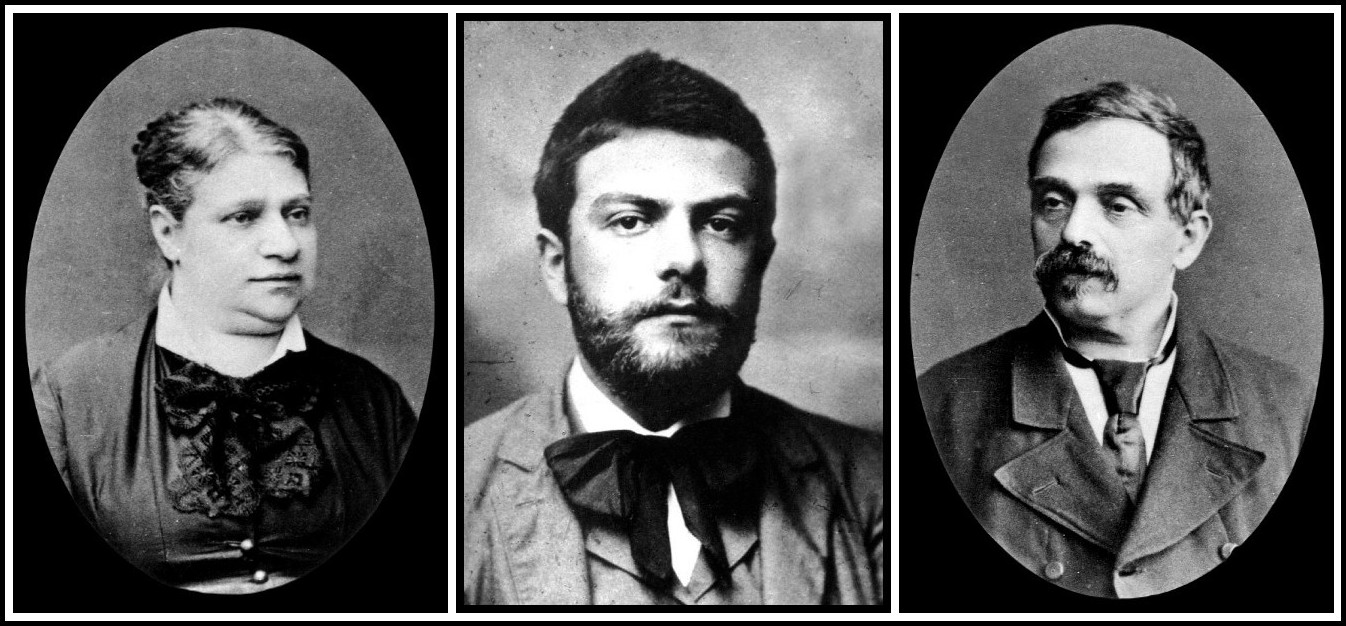

If the paradise imagined by Arnim and Brentano’s peasant boy was now beyond reach, and the only paradise humans could aspire to was here on earth, for a brief moment on a summer afternoon, how were the men and women of his time—the audience he composed for—to come to terms with death and loss, the blows for which a belief in paradise had long served as consolation? Religious music and art had given the mater dolorosa (the grieving mother) a privileged place in its rhetoric of comfort. The grieving father or brother was less frequently depicted, and here was a subject close to Mahler’s heart. Between 1901 and 1904, he composed five songs for male voice and orchestra, based on poems that a distraught young German professor, Friedrich Rückert, had written seventy years before, on the death of two of his children from scarlet fever. Alma, Mahler’s fiancée by then, thought he was tempting fate to choose such a subject, but this was a terrain, after all, that he knew only too well.

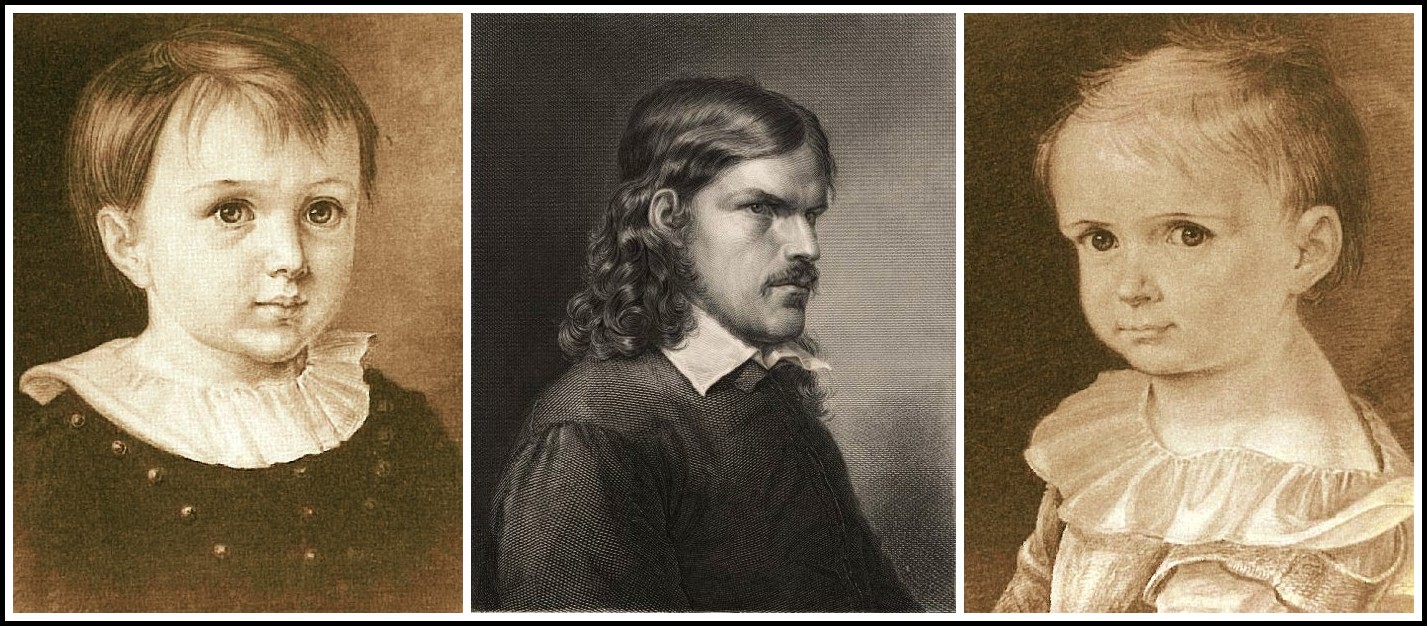

ERNST RÜCKERT | FRIEDRICH RÜCKERT | LUISE RÜCKERT

The paintings of the children are by Rückert’s friend Carl Barth. The engraving of Rückert is by Samuel Amsler & Albrecht Fürchtegott Schultheiß.

‘In the winter of 1833-34, the Rückert children were stricken with scarlet fever: August, Karl and Leo got off lightly, and luckily their big brother Heinrich was away with his grandparents. But two-and-a-half-year-old Luise died on New Year’s Eve, and on January 16, five-year-old Ernst followed her. The mother, who had already lost a child two years earlier, collapsed. But the father did what he had done all his life and would continue to do until the end of his life: he wrote poems, more than five hundred, in six months of intense grief.’ Tilman Spreckelsen, F.A.Z., 14 April 2016

In channeling this fraught material into musical form, Mahler was able to deploy his mastery of the German lieder tradition, using musical shading to give plain words an emotional charge that they might not have been able to convey on their own. This is especially the case with the Rückert poems, which were, as poems, barely mediated expressions of the poet’s grief. Mahler selected just five from several hundred, and then arranged them in a narrative sequence conveying what he imagined a father would feel as he went from disbelief, to wild grief, to regret, and finally to acceptance. The fourth song begins with disbelief: I often think, they have only just gone out / And now they will be coming back home / The day is fine, don’t be dismayed / They have just gone for a long walk.

By the last song, in which Mahler gives musical form to wild emotion, the mourning father is tormented by a guilt he knows cannot bring the children back: In this weather, in this storm / I should never have let the children out / I was anxious they might / Die the next day / Now anxiety is pointless / In this weather, in this storm… The last song begins in wild agitation but ends in serenity. Mahler manages to convey through the last bars, which float away into silence, a state of emotional acceptance in which a parent could believe that the children were at peace so that they could leave grief behind: They rest as if in their / Mother’s house / Frightened by no storm / Sheltered by the hand of God / They rest, they rest / As if in their Mother’s house. Neither in Rückert’s poems nor in Mahler’s reworking of them is there any suggestion that the children are safe in a Christian heaven. There is only music: a gently ebbing melody that, as someone once said, feels like the touch of your mother’s hand on your head.

The philosopher Martha Nussbaum hears the music of the last Kindertotenlied very differently. It conveys, she writes, ‘the sleep not of comfort but of nothingness.’ The music conveys the ‘knowledge of the impossibility of any loving, any reparative effort.’ Mahler means to say, she maintains, ‘that the world of the heart is dead.’ She seems not to hear the warmth and gentleness of the final bars. The music does evoke the stillness of death, it is true, but for art to be convincingly consoling it must convey the reality of what it seeks to console for. The music, having conveyed the full intensity of disbelief, guilt, and grief in the four preceding songs earns its right to console in the final bars of the last song. The necessary condition of any truly consoling work is that it knows of what it speaks, and because it does, the music earns a listener’s assent to its transformation of the idea of death into a vision of peace and sleep. Mahler certainly knew of what his music spoke. He was unabashed about the autobiographical impulses at work, telling a friend ‘only when I experience, do I compose, only when I compose, do I experience.’ In the Kindertotenlieder, his memories of those coffins passing the door of the tavern in Iglau brought the pain of his own experience to the music. So vivid were these memories that he doubted that his songs would console anyone, confessing ruefully to a friend that he had no idea who could actually bear to hear them. All he knew was that he had put into music the truth of those memories of sorrow.

Richard Horn, Die endlose Straße, 1976

The songs turned out to be an artistic breakthrough, for he managed to create a spare symphonic song form, combining the power of words and the power of an orchestra in a compellingly personal way that proved deeply popular. Artistic success could have been enough for him, but it is also possible that the work itself allowed the composer to make peace with painful memories. This peace, unfortunately, was to be short-lived. When he wrote the first of the Kindertotenlieder, he was an unmarried man of forty-one; when he wrote the last one in 1904, he had been married to Alma for three years and was the father of a daughter he adored, Marie, named in memory of his mother.

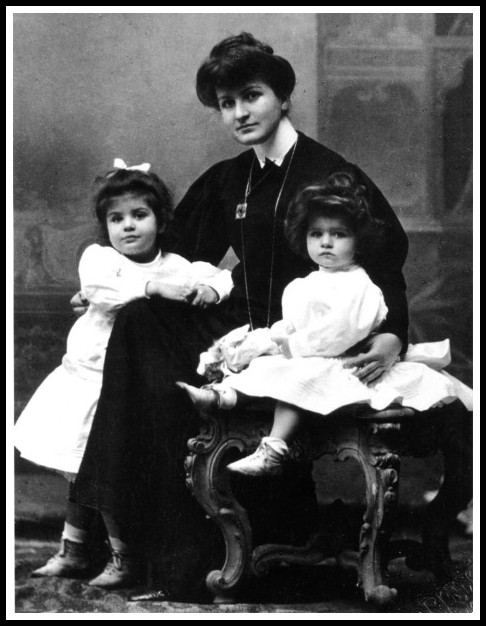

Alma Mahler with daughters Maria (‘Putzi’, left) and Anna (‘Gucki’)

Three years later, in 1907, he left the Vienna Opera, exhausted by professional battles as chief administrator of the house and worn out by his own unremitting perfectionism as a conductor, only to suffer a blow that was to change his life forever. In midsummer, his daughter came down with the same scarlet fever that had claimed Rückert’s children. Little Marie’s struggle for life was ghastly and protracted. Mahler paced outside her room until the sound of her death rattle drove him away. Alma had to assist at the tracheotomy performed to help the child breathe, and when this had no effect, she ran along the shore of the lake where they were staying, crying out her grief. The child’s death was a blow from which neither they nor their marriage ever recovered. Mahler confessed to Guido Adler, his oldest friend from his days in Iglau and now a professor of musicology in Vienna, that once he had lost his daughter, ‘I could not have written these songs anymore.’ Music had enabled him to work through the loss of his brothers and sisters a quarter century before and it helped him to console others, but even music fell silent once the loss was his. In the death of a child music met its match.

Edvard Munch, Anxiety, 1894

In the aftermath of Marie’s death, the work of composing, conducting orchestras, and shaping a repertoire offered him a respite from grief, but her loss changed his music. There was happiness in what he was to write afterward, but always with an undertow of sorrowful awareness that joy was fleeting and brutally revocable. Mahler never referred again to the death of his daughter, but sorrow continued to seek expression in his work, in the brooding Andante of his Sixth Symphony composed in 1907 and in the Abschied, the final movement of Das Lied von der Erde, composed in 1908. Mahler set a Chinese poem of regret and farewell to music for this final song. Its verses included these lines: All desire now turns to dreaming / Weary mortals make for home / To recapture in sleep / Forgotten happiness and youth / Birds huddle silently on their branches / The world falls asleep.

Lin Liang, Starlings in Autumn Branches, c. 1450 | Chen Hong-shu, Self-Portrait with Butterfly, c. 1640

As in the final song of the Kindertotenlieder, Mahler composed an ethereal, floating musical line to convey the haunting melancholy of these final verses: Where am I going? / I go into the mountains, I seek peace for my lonely heart. / I am making for home, my resting place! / I shall never roam abroad again— / My heart is still and awaits its hour! / Everywhere the dear earth / Blossoms in spring and grows green again! / Everywhere and forever the distance shines bright and blue! / Forever… forever… In the final bars of the Abschied, as the singer whispers ‘forever, forever,’ the music lifts the listener out of the world of pain and regret into a shimmering world of sound very slowly fading into silence. As in Kindertotenlieder, as in the final bars of his Ninth Symphony, Mahler brings the listener and the music to the very edge of silence, as if to mark the place where music’s consoling work has to end, and the listener must go on to find meaning on his or her own.

Ma Yuan, Dialogue with the Wind, c. 1220 | Qi Bai-Shi, Morning Glory, c. 1950

III. CONSOLATION TODAY

ONE

Today consolation has largely passed out of the modern vocabulary; music has other work to do beside consolation, and new vernaculars of understanding have taken the place of the religious. Loss and sorrow can now be understood as illnesses from which we can recover. This development, which began in Vienna in Mahler’s time, has been called the triumph of the therapeutic. When Mahler sought Freud’s counsel in Leiden in August 1910, it was a meeting of two masters of the language of emotion. One had given form to the ascendant language of the talking cure, with its claims to science, its hostility to religious consolation, and its belief that grief, neurosis, anxiety, and sorrow could be cured by bringing emotion to utterance. The other was a master of the language inherited from Beethoven and Wagner, now in a desperate state of mind, tormented by his wife’s infidelity, unable to finish his Tenth Symphony, driven to scrawling on his score, ‘My God why hast thou deserted me?’ words of desolation as old as the Psalms.

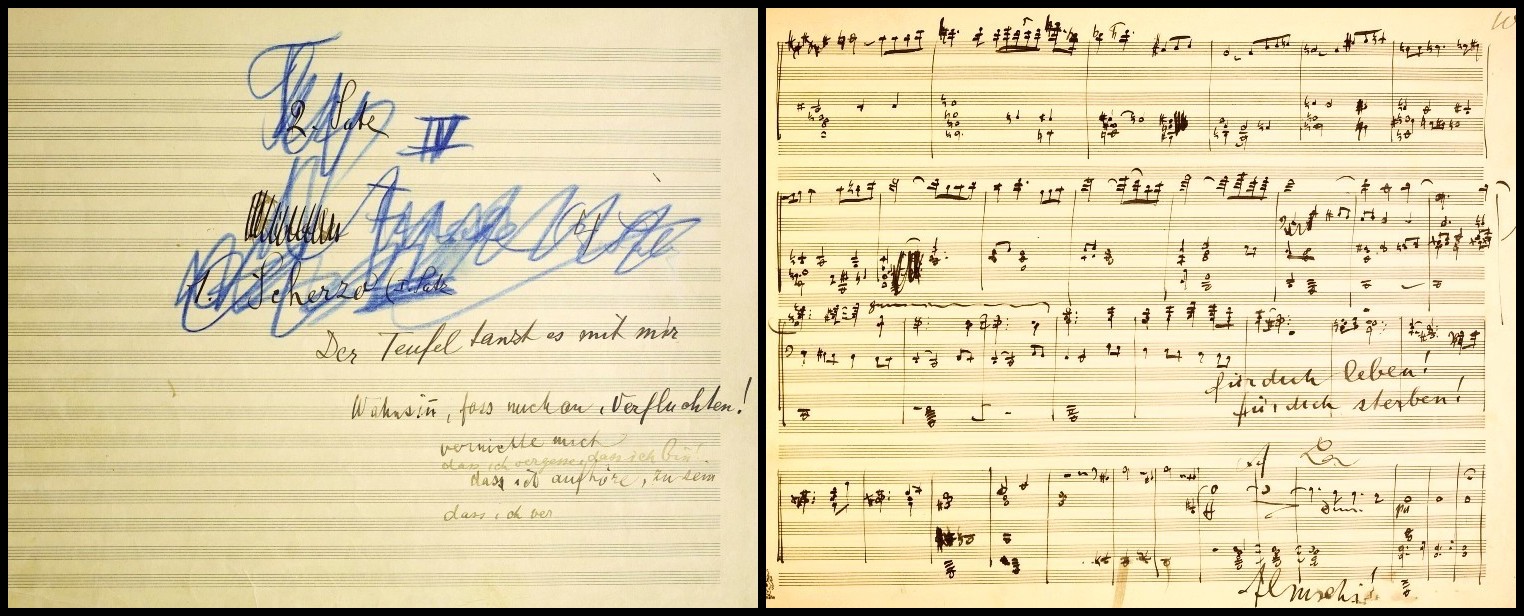

TWO PAGES FROM MAHLER’S MANUSCRIPT OF THE TENTH SYMPHONY

‘The devil is dancing with me. Madness, touch me, you accursed one! Destroy me so that I forget that I am! So that I cease to be, so that I perish.’ | ‘Live for you! Die for you! Almschi!’

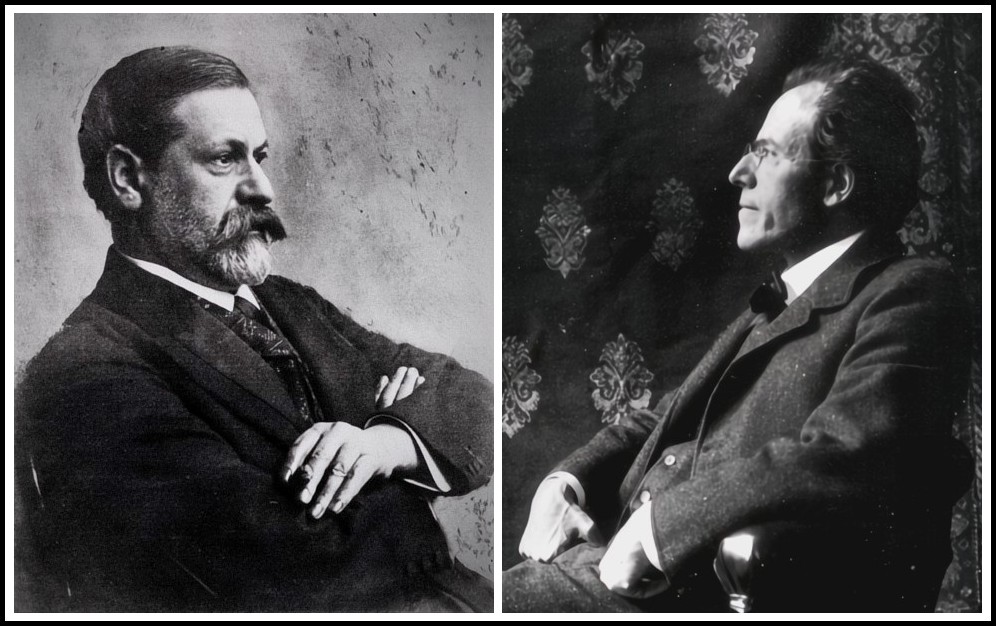

They met for lunch and then walked up and down the canals for four hours: two Jews from Moravia, one in need of reassurance and comfort from the new science of the mind, the other seeking to capitalize on a celebrity encounter that he hoped would add to the prestige of a discipline still struggling at the edges of medical respectability. It was a caricature of an analysis, of course, since Mahler did not spend any sessions on the couch. Perhaps he feared a cure would leach away the tensions that drove his art. In any event, there was no time: Mahler’s heart condition had been diagnosed, and he believed he was a dying man. He was certainly a desperate one. Freud reassured him that Alma would not leave him, since her father fixation was the equal of his mother fixation. Mahler returned to work, comforted and reassured, and Freud came away impressed by Mahler’s astonishingly quick grasp of the basic language of psychoanalysis and his acceptance of its insistence on returning to the primal scenes at Iglau.

Sigmund Freud, 1906 | Gustav Mahler, 1909

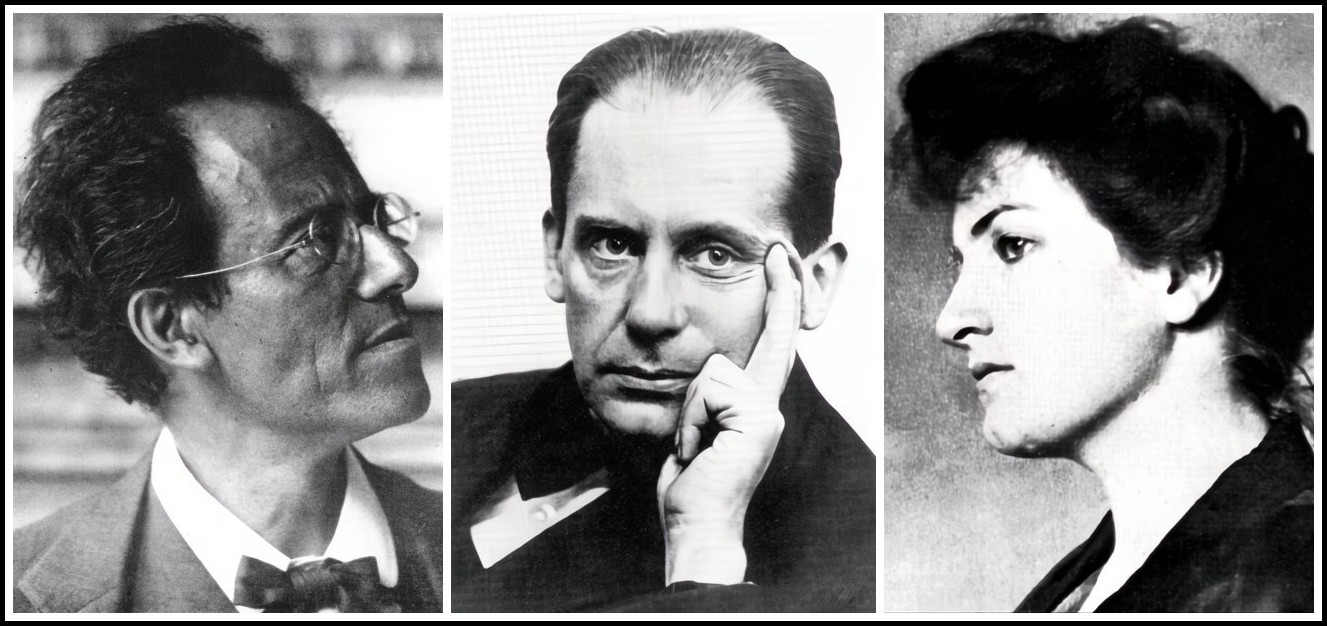

Mahler reconciled himself to his wife’s infidelities and plunged again into conducting, this time in New York, but he never completed the Tenth Symphony. His heart condition deteriorated, and in 1911 he returned to Vienna to die. He chose to be buried in the Grinzing cemetery, next to his daughter Marie. Days after his death, Freud presented the Mahler estate with a bill for his services. A callous or vulgar gesture, one might think, but it was Freud’s way of insisting that the meeting at Leiden had been a medical consultation and should be acknowledged as such, through payment of a fee. Freud admitted much later that he had not managed to dig more than a tunnel beneath the edifice of Mahler’s neurosis. The edifice—made of sorrow and memory and hope—had been the place from which the music had come. Freud’s tunnel never got close to the heart of it, nor to the sources of that immense consolation that Mahler’s work has provided ever since to those who, in listening to him, suddenly think, here is someone who understands what I feel, someone who understands this loneliness, desperation, or sorrow, this exaltation that may soon turn to silence.

Gustav Mahler | Walter Gropius, Alma’s lover | Alma Mahler

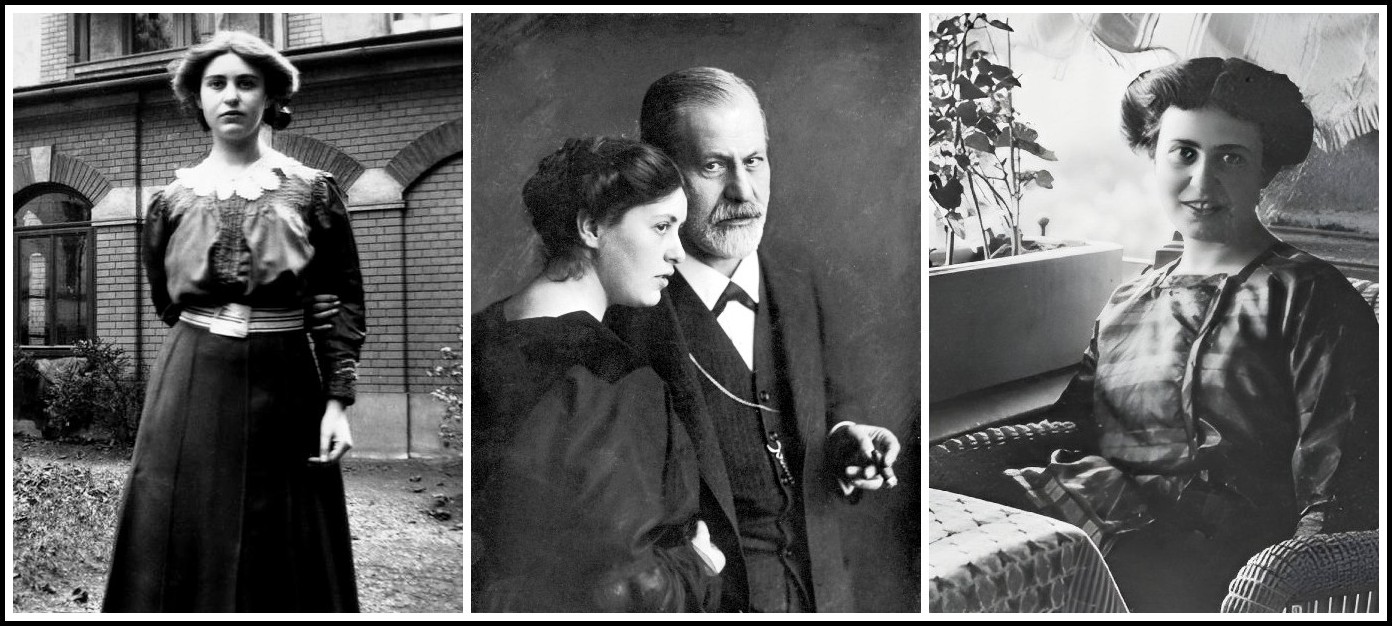

The new science of psychoanalysis promised to replace the false consolations of religion with self-knowledge achieved through therapy, yet even the inventor of the new faith had to confess its limitations. When Freud’s own daughter died in the postwar influenza epidemic in 1920, he admitted sadly to a friend that her loss left him defenseless and alone. The language of psychoanalysis helped him to understand the blow but not to bear it: Since I am the deepest of unbelievers, I have no one to accuse and know that there is no place where one can lodge an accusation… but way deep down I sense the feeling of a deep narcissistic injury I shall not get over.

Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) and his daughter Sophie (1893-1920)

TWO

The deaths that haunted Dorothea von Ertmann, Friedrich Rückert, Gustav and Alma Mahler, and Sigmund Freud are now infrequent. Thirty years after Mahler’s death, sulfa drugs and penicillin began to be used in hospitals, and the scarlet fevers that had carried off their children and blighted their lives became mere infections that prompt care could cure. Yet children still die, and their deaths can appear still more senseless and cruel when modern medicine proves to be of no avail. In the absence of consolation, only faith in medical miracles remains, and the search for them often ends in cruel disappointment. As for Freud’s talking cure, it once advanced with all the prestige of a science and the organizational energy of a cult. Now no longer the therapy of choice, it has been displaced by a host of competing therapeutic regimens that have come on the market to medicate misery.

De-Medicalizing Misery I: Psychiatry, Psychology & the Human Condition | De-Medicalizing Misery II: Society, Politics & the Mental Health Industry

If anything, music’s importance as consolation has only grown in an age that medicates grief and treats sorrow as an illness. In moments of grief and despair, there is something unsayable about the experience that only music seems to express. Musicologists have spoken of the ‘floating intentionality’ of music, this sense that music is about something but resists pinning down what precisely that something might be. Music calls on listeners to complete its implicit meaning, and when we do so, we have a feeling of understanding our own emotions that is central to the experience of consolation. Music can have these tidal effects only when we are ready for them. In the first extremity of distress, we might not turn to music at all. A person in pain may have no time for beauty, for sound, for anything. The time when music can help might come years later, when you are sitting in a concert, listening to a musician play a passage, and you are swept away. Memories return, not now unbearable, but still so strong that you sit in the darkened hall, concealing tears from the people on either side, feeling gratitude that this music releases you so that the work of consolation can begin. This delayed effect, sometimes of years, of decades, teaches us that consolation may be the work of a lifetime.

Mark Rothko, Light Earth and Blue, 1954

THREE

In this work, in which grief or regret slowly gives way to consolation, the dead play their part. They keep vigil by our sides. It is as if they would console us, if they only could. A musician I know lost his own daughter in a single instant in a tragic accident many years ago. She was the eight-year-old he took to concerts, who sat with him and tapped her feet, her face rapt in attention. She was the one who seemed to have inherited whatever gift he had, and so they were especially close. When I asked him how he had dealt with her death, he said he kept working. There was nothing else to do. What did he think now, decades after her death? ‘I thought she had been spared suffering. Her life had been complete. It was full. She lived it. She was spared the rest.’

Mark Rothko, No. 207, 1961

Instead of lamenting a life cut short, he had learned, after many years, to think of his eight-year-old’s time on earth as a life fully lived and moreover, one spared some of the griefs that he himself had suffered. A working life in music had helped him to begin to live again. When I asked what music had consoled him, he found it hard to single out one piece because there were so many, but he settled on the final trio in Richard Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier, the soaring melancholy with which the Marschallin accepts her own aging, the death of love, and the triumph of her young rival. My musician friend did not mention the Kindertotenlieder. Perhaps it was too close for comfort. But then he added an afterthought. He had never forgotten his daughter, not for an instant, and he counted that as a victory. Every night, even now, he said, when he is about to perform, when he stands in the wings offstage, waiting to go on, she is there with him, a presence, a spirit, just there, visible to no one but him, a child watching silently as he moves forward onto the lighted stage.

Mark Rothko, Seagram Mural Sketch, 1958

John Singer Sargent, The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, 1882 (detail)

MICHAEL IGNATIEFF: THREE BOOKS

CLICK ON AN IMAGE TO GO TO THE BOOKS PAGE ON THE AUTHOR’S WEBSITE

As a writer and historian, Michael Ignatieff has been publishing work since the mid-1970’s. He has written fiction and non-fiction, screenplays, reviews and essays – altogether translated into 20 languages. His 20 books keep returning to a few recurrent themes: human rights and the fate of moral universalism in a world of clashing and competing values; liberalism as a political theory, as a practice and as a way of life; and our struggle to maintain democratic freedoms. His most recent work—especially On Consolation—has taken him in a new direction: to thinking about the history of our attempts to console ourselves for the timeless ordeals of life– death, loss and tragedy—and how we manage, despite everything, to live in hope.

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2024 | All rights reserved

Comments