Resummoning Something That Was Once Present

KINDERTOTENLIEDER: GUSTAV MAHLER AND ‘CALLING BACK A VOICE’

Julian Johnson

Posted by kind permission of Julian Johnson, Regius Professor of Music, Royal Holloway, University of London

From Julian Johnson, Mahler’s Voices: Expression and Irony in the Songs and Symphonies (Oxford University Press, 2009) pp. 71-82

NOTE: CLICKING ON ‘EXAMPLE…’ IN THE BODY OF THE TEXT WILL BRING UP A PDF FILE OF THE MUSIC UNDER DISCUSSION.

Gustav Mahler’s Glasses

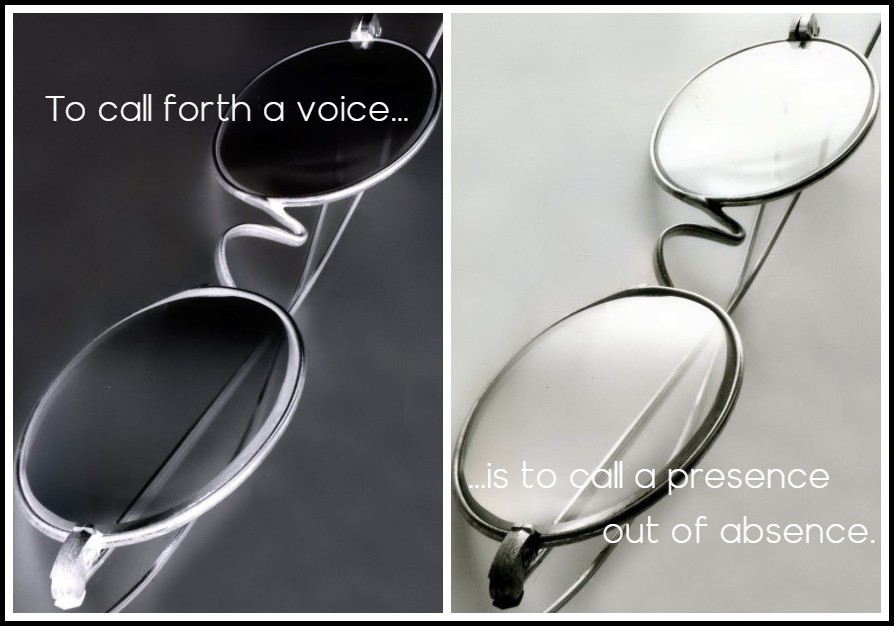

To call forth a voice, to invoke or summon a voice, is to call a presence out of absence. The voice realizes a presence through the physicality of sound, a presence that is at once perceptible and sensuous yet intangible and incorporeal. It emanates from the body of the vocalist and yet, as sound, remains ungraspable.

Degas, Two Studies for ‘Music Hall Singers’, 1880

In this way, invocation has always been central to religious practice. The deity is called into presence through the voice, while yet remaining ineffable, at once immanent and transcendent. The power ascribed to a later secular and instrumental music owes something to these shamanic origins.

Gregorian Chant: Wiener Hofburgkapelle | Benedictine Abbey Clervaux | Benedictine Abbey Gerleve

But if the power of music is bound up with its origin as a kind of invoking, equally important is its capacity for revoking, calling back, resummoning something that was once present. Revoking includes the idea of canceling or annulling: the passage of time is temporarily annulled by a music that makes the past ‘come alive’ again, as space is canceled out by the illusion that what is physically absent is made present in sound.

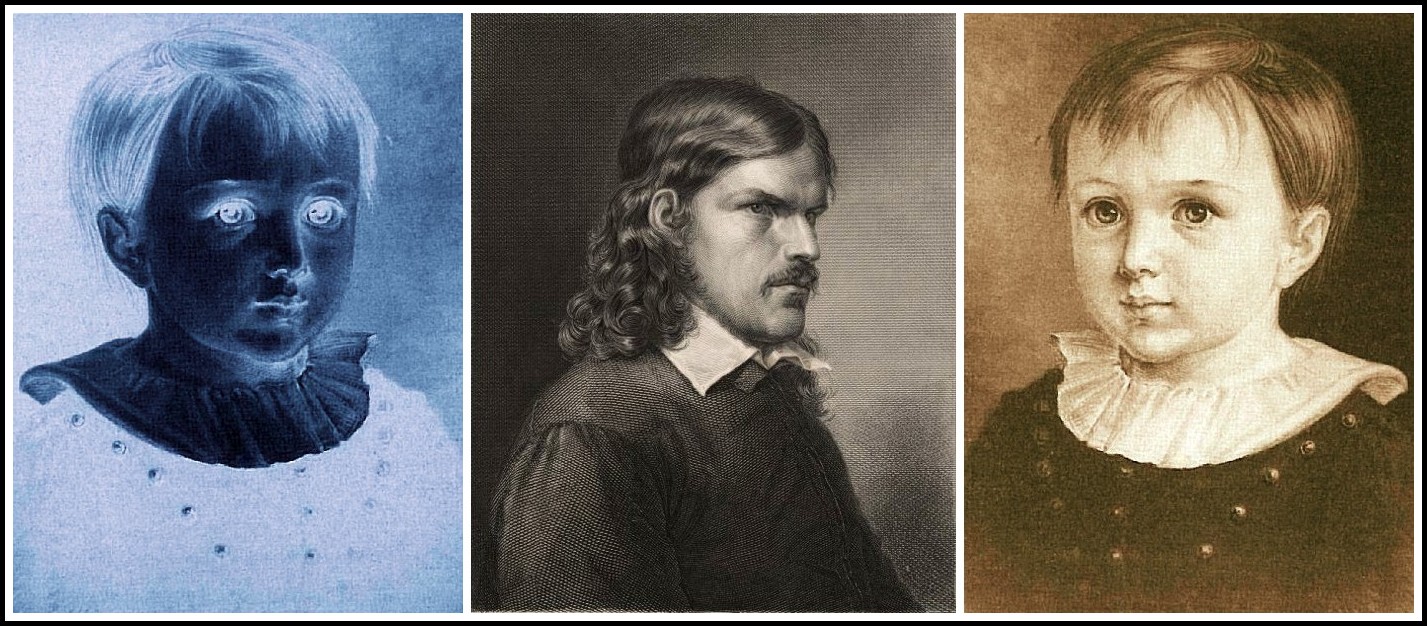

Joshua Reynolds, A Child Asleep, 1782 | Gerard ter Borch, Singer and Lute Player, 1689 | Antonio Mancini, Almond Blossoms, 1876

Mahler’s music often presents a kind of revoking, an annulment of some absence or lack, often conceived in terms of temporal or spatial distance. Nowhere is this more pointed than in the musical revocations of death itself. At such moments, Mahler’s music assumes an orphic quality, making present once more what was lost to death, This orphic capacity to resummon presence is often signaled by a certain use of the harp, framing the arrival of the summoned voice, as it does in Das klagende Lied, the ‘Gesang’ theme of the first movement of the Second Symphony, the transition to the Finale of the Fourth Symphony or the Adagietto of the Fifth. Nowhere is it more evident, however, than in the Kindertotenlieder, songs predicated on the idea of revoking the radical absence of death through the presence conferred by an invoked voice. They exemplify a central category of Mahler’s music, what Hans Heinrich Eggebrecht and Hermann Danuser have referred to as its quality of ‘as if’ (als ob). Mahler’s music often behaves ‘as if’ something were the case: the visionary episode, whether of reminiscence or anticipation, is a fragile statement of how things might have been, or might become, a musical space in marked contrast to the ‘reality’ that precedes and follows it.

Odilon Redon (1840-1916), Head of Orpheus I

Mahler takes his lead from Friedrich Rückert here, finding a musical corollary to speaking in the subjunctive. ‘Now will the sun rise as brightly / as if no misfortune had befallen in the night!’ begins the first song. The second surmises that in life the children had looked with such intensity as if to burn a memory in their parents’ hearts, eyes which now will be as if they were stars. The children’s eyes seem to say ‘we would like to stay’ (wir möchter bleiben). In the third song, the children’s father tells how, when their mother comes through the door, he looks at half-height, ‘there, where your dear little face would be’. The fourth begins with the self-delusion that it is as if the children had merely gone out for a walk on a beautiful day. In the fifth, the parent laments, ‘in this weather, in this tumult, I would never have sent the children out’ but concludes with the utterly peaceful thought that ‘they are sleeping as though in their mother’s house’.

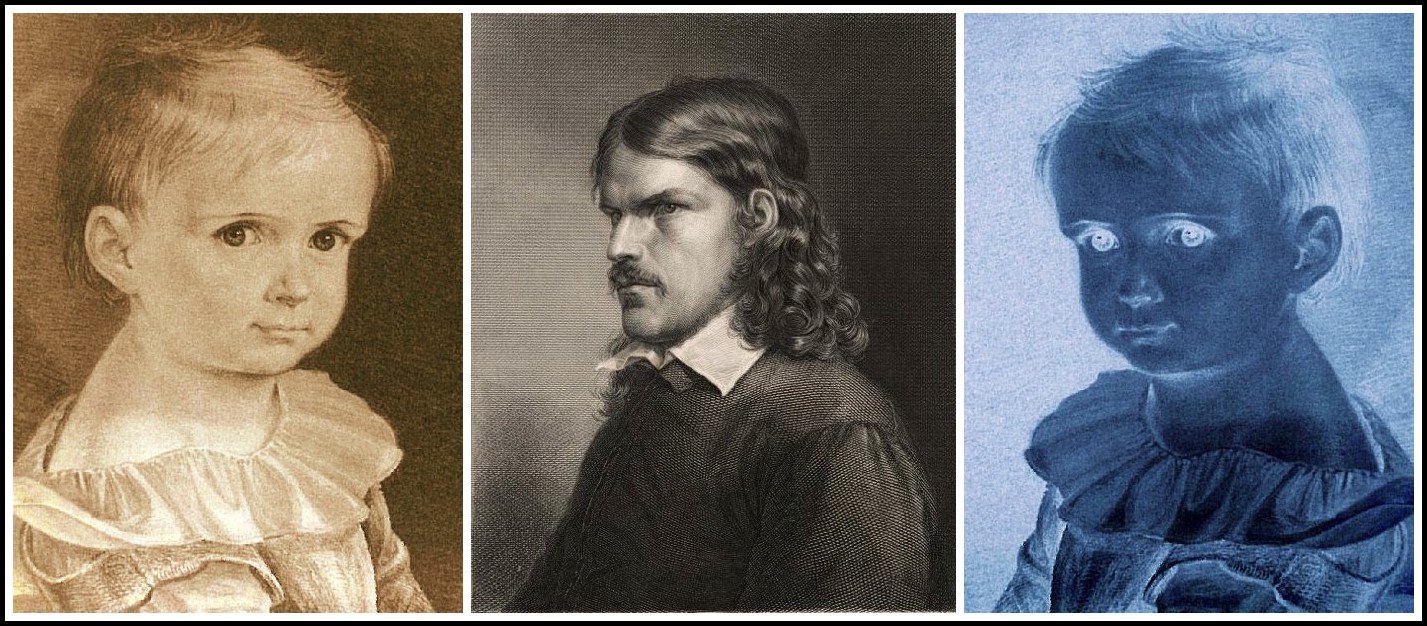

ERNST RÜCKERT | FRIEDRICH RUCKERT

The painting of Ernst is by Rückert’s friend Carl Barth (the image on the left is colour-inverted). The engraving of Rückert is by Samuel Amsler & Albrecht Fürchtegott Schultheiß.

The opposition of a bare, empty, or even absent voice, and a fragile lyrical hope is not uncommon in Mahler. But what all of the Kindertotenlieder underline is the function of the fragile lyrical voice as a revocation, a calling back into presence of what is otherwise absent. The musical voice here is often bare, as in the exposed two-part counterpoint at the start of the first song. The emptiness of bereavement borders on the catatonic, the inability to give voice at all; the last lines of the vocal part in the first song are marked Erschütterung (literally, ‘in shock’). The voice of the protagonist is thus caught between trauma and the fragile, impossible hope that things might be other than they are. In the first song, this fragile ‘as if’ is conveyed by the subtle shift from the empty counterpoint of the opening ten bars in D minor, to the hint of a lyrical, songlike voice and texture in D major (Example 2.9). This change is effected by the addition of an accompaniment figure in the harp (doubled in the violas), the new and rich sonority of a four-part chord, and the doubling of the vocal line by the cellos. Where the vocal line had descended in the opening bars, its quality of fragile hope is now marked by ascent, though Mahler marks it to be sung mit verhaltener Stimme (with a held-back voice), as if hardly daring to suggest that ‘no misfortune had befallen in the night.’

LUISE RÜCKERT | FRIEDRICH RUCKERT

The painting of Luise is by Rückert’s friend Carl Barth (the image on the right is colour-inverted). The engraving of Rückert is by Samuel Amsler & Albrecht Fürchtegott Schultheiß.

The music temporarily realizes the longed for ‘what if’; the turn to D major, the sudden richness of tone and triadic stability and the doubling of the melodic line do not long for presence, they make present. And the tension between this and the absence that surrounds it makes for a remarkable quality of dissonance. Mahler’s predecessor in this undoubtedly is Schubert. In the first song of Winterreise, it is the sudden turn to the tonic major (also D, as here) that is the most poignant of all; the fragile and ephemeral realization of the content of memory is far more dissonant than the frozen emptiness that surrounds it. The poignant counterpoint of Rückert’s text, of the numbness of bereavement and the luminous presence of the children recollected in memory, is thus embodied here by a simple but fundamental opposition of Mahler’s music. As in Schubert, this use of the major and minor mode as a tonal contrast rather than a functional modulation proposes a simultaneity of two states. And as in Schubert, and quite unlike Beethoven, expressive dissonance remains unresolved; one element does not give way to the other, but the two coexist to the end.

Gustav Mahler | Franz Schubert

The same opposition shapes the second song. In ‘Nun seh’ ich wohl’ the Tristan-esque longing of the opening figure (a cipher of absence) gives way to a brief moment of presence that, in tone and construction, is similarly akin to the Liebestod of Wagner’s opera. The D major passage, in 6/4, lasts for only three bars before the return to ‘reality,’ but its summoning of a presence in spite of death is palpable; the sentiment of the words remains hypothetical (that the children’s eyes had shone so brightly in their lifetimes as if to say that they wished to stay here with their mother), but the music momentarily realizes such a presence (Example 2.10). The fullness of the musical voice at this point delivers a physicality that contrasts strongly with the emptiness implied by the music either side of this passage. The power of the musical voice to invoke the presence of what is lost to death is nowhere more evident, in Mahler or anywhere else.

Jeanne-Michèle Charbonnet (Isolde) & Clifton Forbis (Tristan) in Richard Wagner, Tristan and Isolde, Grand Théâtre de Genève 2005 | Zachary Kadolph, Unsplash

The fifth and final song of the cycle, ‘In diesem Wetter,’ makes the idea of revocation more explicit by constructing a reversal of the expected poetic metaphor; the storm that should distress the mother, thinking of her children outside, is instead the occasion for a gentle D major lullaby (Wie ein Wiegenlied). Mahler produces here his most sustained ‘as if,’ redefining the preceding storm music by choosing to end in the containment of a lullaby. The D minor orchestral storm that opens this song is marked Mit ruhelos schmerzvollem Ausdruck (with restless and painful expression). The D major ending, however, restores a state of absolute peace with its setting of the words ‘sie ruh’n als wie in der Mutter Haus’ (they rest as if in their mother’s house). The maternal space is constructed here by the static D major triad and the undisturbed metrical and textual regularity that persist to the closing bars. This is underlined by a sustained pedal A (viola, then horn), which takes its cue from the glockenspiel, the childlike bell sound that resonates throughout these songs like the distant echo of the children’s voices. The orchestral sonority is defined by the simple two-part counterpoint of voice and violin, with the accompaniment figure given by the celesta (doubled in the 2nd violins), amplifying the childlike association of the glockenspiel heard a few bars earlier. The gentlest of orchestral comments follows the closure of the vocal line—first a melody in the horn and then a counter-melody in the cellos.

Julius von Leypold, Wanderer in the Storm, 1835 | Samuel Baruch Halle, Mother and Child, 1859

The emotional power of this D major close would seem to be out of all proportion to its simplicity and yet derives its force precisely from that simplicity. It exemplifies the reversal of expressive values effected by Mahler’s music. Pushed to an emotional extreme, as the death of children here occasions, the poetic voice fails to find adequate expression (hence its broken and shuddering quality). The bareness of Mahler’s counterpoint in these songs, the restraint of the voice rather than an unmeasured outpouring of grief, is the key to their unbearable intensity. The ‘inexpressiveness’ of the voice, its numbed quality, defines negatively the force of what cannot find expression. This is underlined by the use of a third voice in the Kindertotenlieder. Between the bare counterpoint denoting absence, and the fulsome richness of the revoked voice, are moments of intense Ausbrechung (breakout)—impassioned protests that literally breakthrough the otherwise ‘held back’ quality of the voice. In the third song, ‘Wenn dein Mütterlein,’ the father’s numb vocal line is first marked Schwermütig (heavy-hearted or mournful), but what is confined as an essentially inward grief finds two moments of intense breakout, the second of which Mahler directs to be sung mit ausbrechenden Schmerz (with an outbreaking pain). These moments of expressive breakout are marked by a melismatic line that turns painfully back on itself as it descends toward a deferred cadence; in the first the voice is doubled by the cellos high in their register (Example 2.11); in the second, by the violas.

Altered images of Julius von Leypold, Wanderer in the Storm, 1835 | Samuel Baruch Halle, Mother and Child, 1859

At other times, it is left to the orchestral voice to register such an emotional outbreak. The third couplet of the first song (‘You must not enfold the night within you’) provokes a violin countertheme (played without mutes for the first time and marked mit großem Ausdruck) that constitutes an emotional overflowing that the traumatized voice itself cannot express. Its brief melismatic gloss on the vocal line is immediately amplified by the whole orchestra with an intensity that is otherwise quite at odds with this song. In the fourth song, ‘Oft denk’ ich, sie sind nur ausgegangen,’ the outwardly sanguine melodic line has a quality of normality that projects the make-believe of an unchanging, everyday world. This acts as a kind of emotional control, a repressive device that almost succeeds but for an intense moment of breakout in the closing bars of the song. The vocal line is painfully distorted in a rising sequence of one-bar phrases that twist the final line of text out of its hitherto unruffled surface (Example 2.12), The orchestra breaks out of its pianissimo accompaniment for no more than a few bars. Normality is restored, and the breaking of the voice is, apparently, contained.

Clovis Corinth, The Rumpf Family, 1901

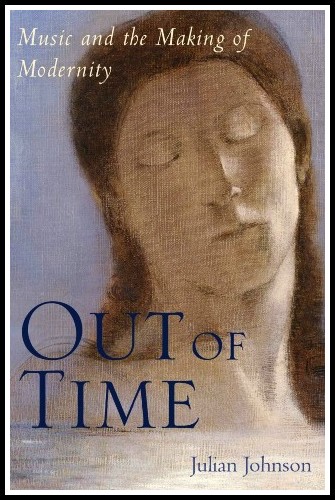

JULIAN JOHNSON: THREE BOOKS

CLICK ON AN IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

KINDERTOTENLIEDER | SONGS ON THE DEATH OF CHILDREN

Friedrich Rückert | William Mann, tr. | Kathleen Ferrier, Bruno Walter, Wiener Philharmoniker

I. Nun will die Sonn’ so hell aufgehn

Nun will die Sonn’ so hell aufgehn

als sei kein Unglück die Nacht geschehn.

Das Unglück geschah nur mir allein

Die Sonne sie scheinet allgemein.

Du mußt nicht die Nacht in dir verschränken

must sie ins ew’ge Licht versenken.

Ein Lämplein verlosch in meinem Zelt.

Heil sei dem Freudenlicht der Welt.

And now the sun will rise as bright

as if no ill-luck had befallen in the night.

The ill-luck befell me alone

and the sun shines all around.

You must not enclose the night within you

you must drown it in eternal light.

A little light went out in my tent.

Hail to the gladdening light of the world!

II. Nun seh’ ich wohl, warum so dunkle Flammen

Nun seh’ ich wohl warum so dunkle Flammen

ihr sprühtet mir in manchem Augenblicke.

O Augen! O Augen!

Gleichsam um voll in einem Blicke

zu drängen eure ganze Macht zusammen.

Doch ahnt’ ich nicht, weil Nebel mich umschwammen,

gewoben vom verblendenden Geschicke,

daß sich der Strahl bereits zur Heimkehr schicke,

dorthin, von wannen alle Strahlen stammen,

Ihr wolltet mir mit eurem Leuchten sagen:

Wir möchten nah dir bleiben gerne

Doch ist uns das vom Schicksal abgeschlagen.

Sieh’ uns nur an, denn bald sind wir dir ferne.

Was dir nur Augen sind in diesen Tagen

in künft’gen Nächten sind es dir nur Sterne.

Now I understand why such dark flames

were strewn on me when you looked at me.

O eyes! O eyes!

As if in one look

you would compress your whole force.

I did not know then (for mists surrounded me,

woven by fate to dazzle me)

that the beam was already turning towards home,

there, whence all beams spring.

You wanted to tell me with your rays:

We long to stay near you

but fate will not let us.

Look at us now, for soon we shall be far away.

These that are eyes today

in nights to come will be stars.

III. Wenn dein Mütterlein tritt zur Tür herein

Wenn dein Mütterlein tritt zur Tür herein

und den Kopf ich drehe, ihr entgegen sehe,

fälllt auf ihr Gesicht erst der Blick mir nicht,

sondern auf die Stelle, naher nach der Schwelle,

dort, wo würde dein lieb’ Gesichtchen sein,

wenn du freudenhelle trätest mit herein,

wie sonst, mein Töchterlein.

Wenn dein Mütterlein tritt zur Tür herein,

mit der Kerze Schimmer, ist es mir als immer

kämst du mit herein, huschtest hinterdrein,

als wie sonst ins Zimmer!

O du, des Vaters Zelle,

ach, zu schnell erlosch’ner Freudenschein!

When your dear mother comes in at the door

and I turn my head to look at her,

my gaze falls first, not on her face,

but on that spot, closer to the threshold,

yes, there where your dear little face would be

if you were entering with her, bright and happy

as you were, my little daughter.

When your dear mother comes in at the door,

with the candlelight it seems that

you come in with her, stealing behind her

into the room as you used.

O you, your father’s flesh and blood,

glad light too quickly quenched!

IV. Oft denk’ ich, sie sind nur ausgegangen!

Oft denk’ ich, sie sind nur ausgegangen.

Bald werden sie wieder nach Hause gelangen.

Der Tag ist schön! O, sei nicht bang!

Sie machen nur einen weiten Gang.

Jawohl, sie sind nur ausgegangen

und werden jetzt nach Hause gelangen.

O, sei nicht bang, der Tag ist schön!

Sie machen nur den Gang zu jenen Höh’n!

Sie sind uns nur vorausgegangen

und werden nicht wieder nach Hause verlangen!

Wir holen sie ein auf jenen Höh’n!

Im Sonnenschein!

Der Tag ist schön auf jenen Höh’n!

I often think they have only gone out:

soon they will come home again.

It is a beautiful day, do not be anxious.

They have only gone out for a long walk.

Yes, indeed, they have only gone out

and they will be coming home now.

Do not be anxious, it is a beautiful day.

They have only gone for a walk up to the mountains.

They have only gone out ahead of us,

and do not want to come home again.

We will find them on those heights up there

in the sunshine!

It is a beautiful day on those heights.

V. In diesem Wetter, in diesem Braus

In diesem Wetter, in diesem Braus,

nie hätt’ ich gesendet die Kinder hinaus!

Man hat sie getragen, getragen hinaus,

ich durfte nichts dazu sagen!

In diesem Wetter, in diesem Saus,

nie hätt’ ich gelassen die Kinder hinaus.

ich fürchtete, sie erkranken;

das sind nun eitle Gedanken.

in diesem Wetter, in diesem Graus,

nie hätt’ ich gelassen die Kinder hinaus.

ich sorgte, sie stürben morgen;

das ist nun nicht zu besorgen.

In diesem Wetter, in diesem Braus,

nie hätt’ ich gesendet die Kinder hinaus!

Man hat sie hinaus getragen,

ich durfte nichts dazu sagen!

In diesem Wetter, in diesem Saus, in diesem Braus,

sie ruh’n als wie in der Mutter Haus;

von keinem Sturm erschrecket,

von Gottes Hand bedecket,

sie ruh’n wie in der Mutter Haus.

In this weather, in this shower,

I would never have sent the children out.

They were dragged out;

I was not allowed to say anything against it.

In this weather, in this storm,

I would never have let the children go out.

I was afraid it would make them ill,

but those were vain thoughts.

In this weather, in this awfulness,

I would never have let the children go out.

I was afraid they would die tomorrow,

but there is nothing to do about that now.

In this weather, in this awfulness,

I would never have sent the children out.

They were dragged out;

I was not allowed to say anything against it.

In this weather, in this storm, in this shower,

they are resting, as if they were at home with mother.

Frightened no more by storms,

watched over by God’s hand,

they are resting, as if they were at home with mother.

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2024 | All rights reserved

Comments