Earth Spirit & Pandora’s Box

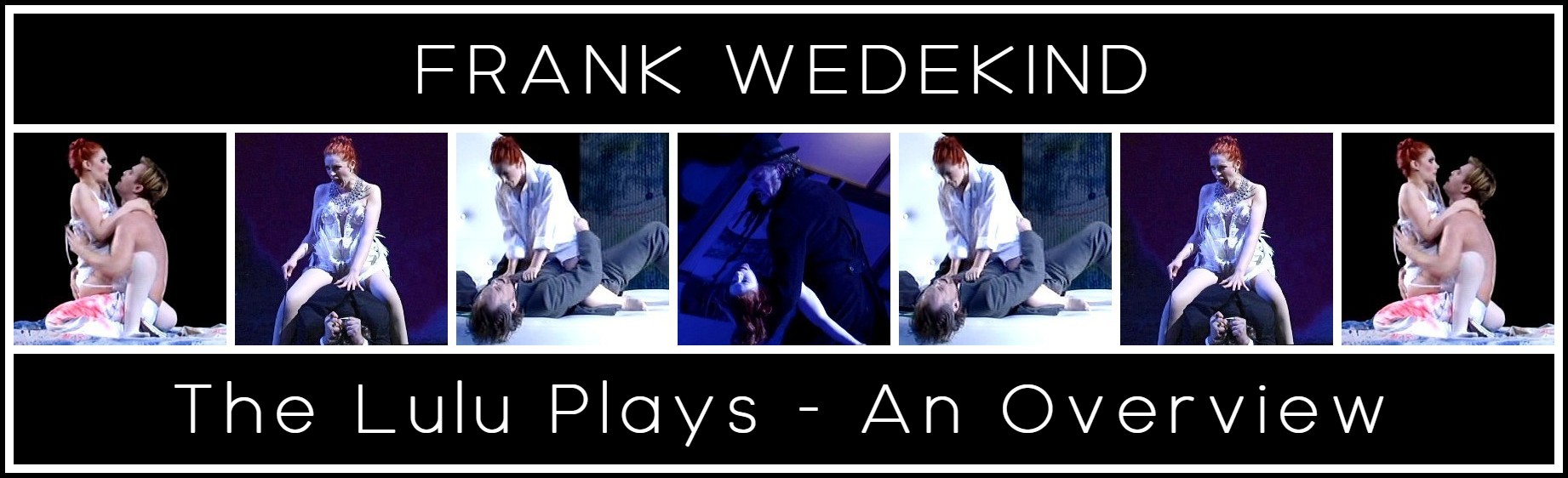

FRANK WEDEKIND: THE LULU PLAYS – AN OVERVIEW

Peter Skrine

Abbreviated from Peter Skrine, Hauptmann, Wedekind and Schnitzler (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1989) pp. 82-96

At the end of Spring Awakening the masked gentleman leads young Melchior off into the wider world. This world, where many things are forbidden but where anything can happen, is the setting for the Lulu plays, Wedekind’s masterpiece. Their composition, stage-history and interpretation are very problematic. Wedekind began work on his new project in 1892, and a version of the first play appeared in 1895 under the title Der Erdgeist (The Earth Spirit). His original intention had been to write one gigantic five-act Lulu drama (he liked to call it his ‘monster tragedy’), but the 1895 text consists only of Acts I, II and IV of the original scheme, with a new Act III. This meant that the last two acts of the original turned into a more or less self-contained sequel which was published in 1902 under the title Die Büchse der Pandora (Pandora’s Box) with an additional first act by way of exposition. The story does not end there.

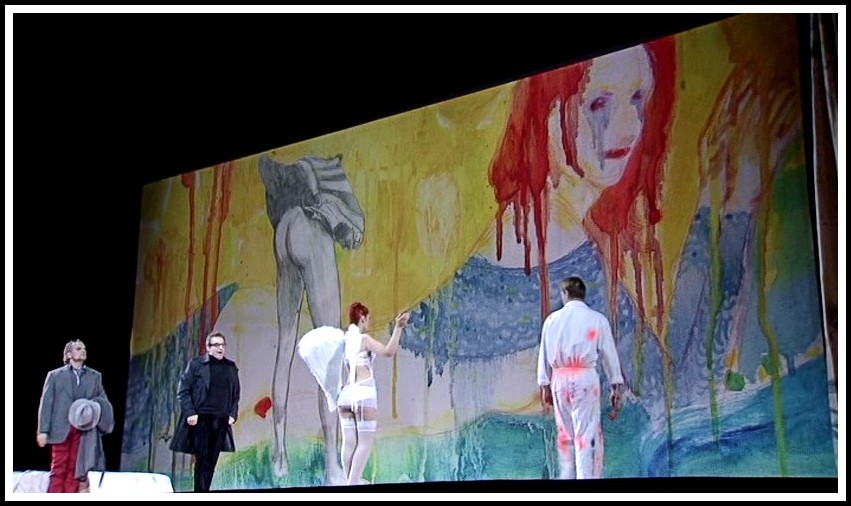

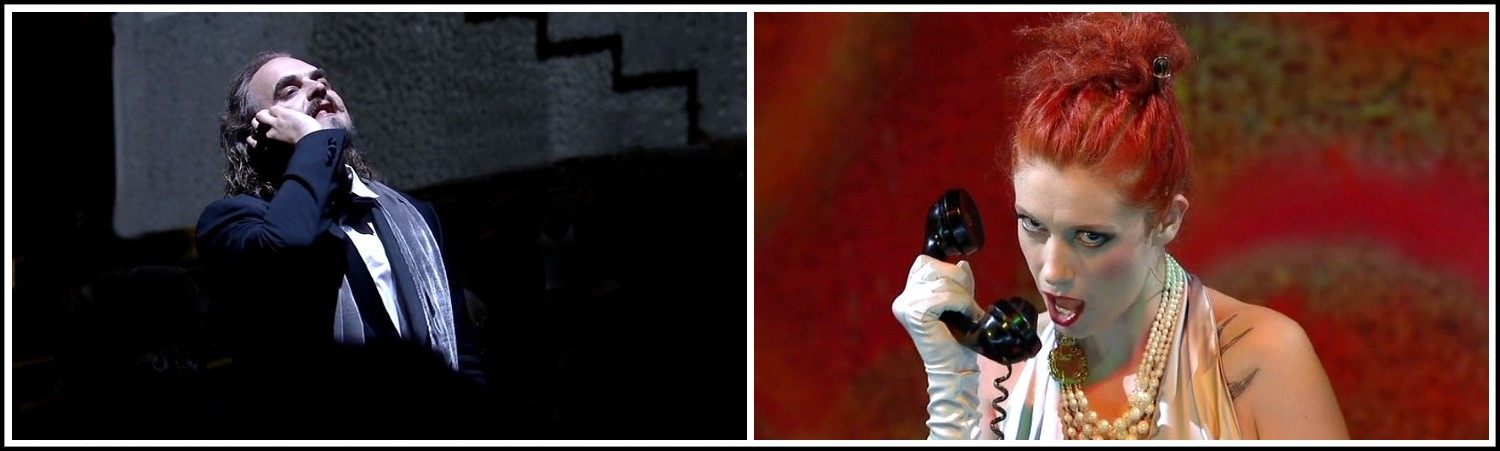

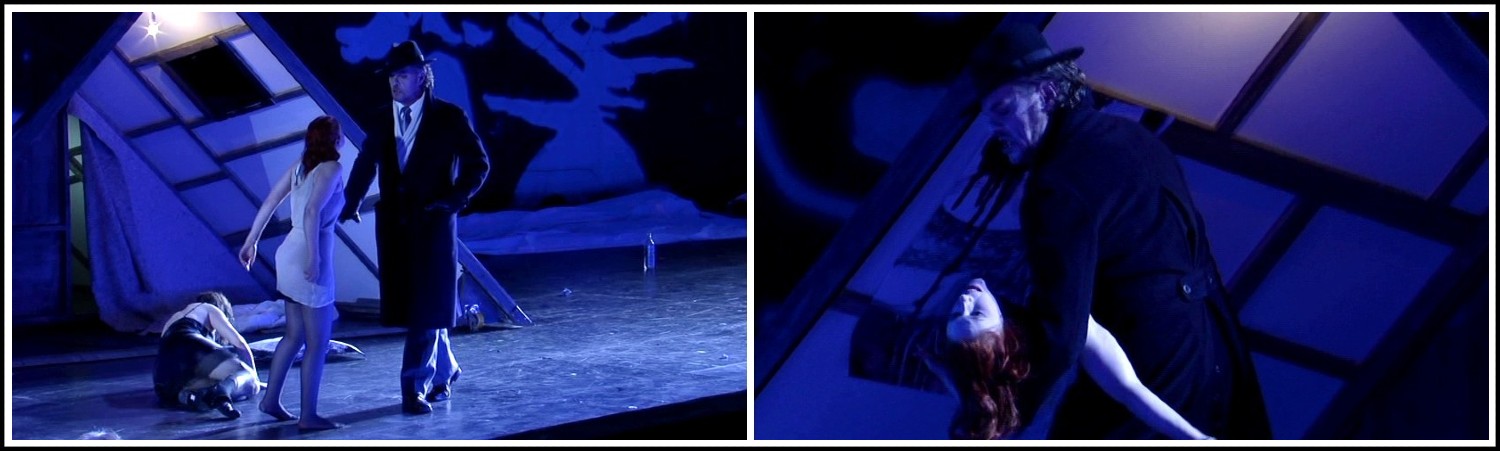

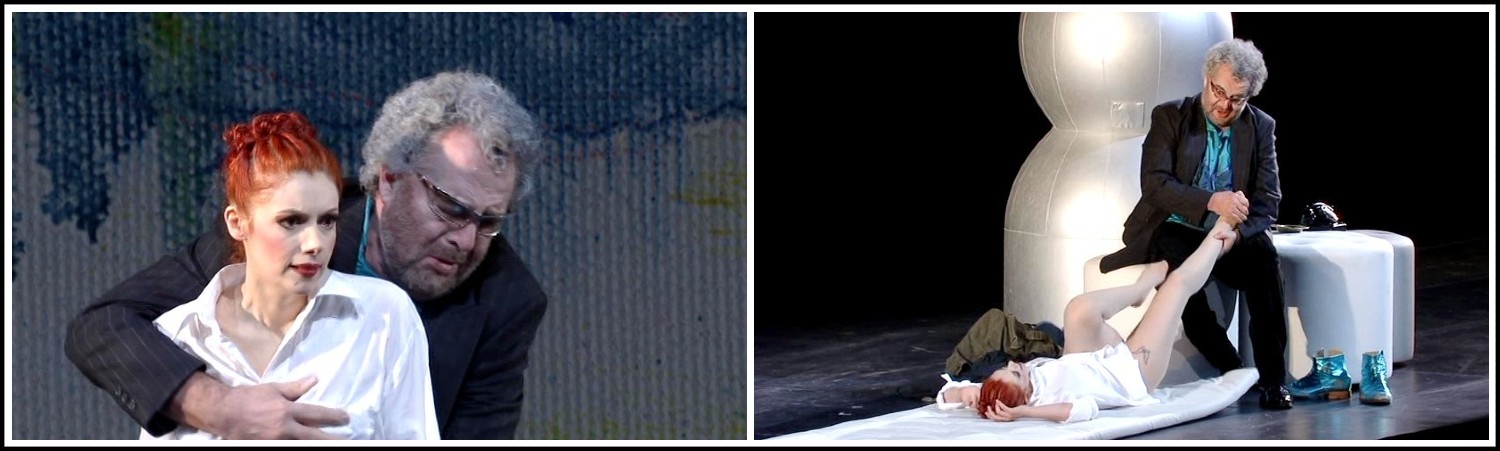

Alban Berg, Lulu, Thomas Johannes Mayer | Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

Constant alterations, in part forced on him by the constrictions of official censorship, and in part by his own changing ideas and his first-hand experience gained in performance, resulted in a number of amended versions, until in 1913 the collected edition of Wedekind’s works finally made a reliable reading-text available. The theatres tended to want something rather different, however: a play which could be performed in one evening, not two. The result was that Wedekind (and others) made a variety of stage adaptations, of which his own 1913 Lulu and that by his daughter Kadidja in 1950 are the most important. These compressed stage adaptations have never really caught on; instead the two Lulu plays have tended to go their separate ways.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Thomas Johannes Mayer | Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

Earth Spirit was first performed in 1898 in Leipzig and taken on tour to other cities, including Munich, by a company calling itself the Ibsen-Theater, with Wedekind himself in the role of Dr Schön. A Berlin production followed at Max Reinhardt’s Kleines Theater in 1902 with the glamorous Gertrud Eysoldt in the role of Lulu. Earth Spirit remains one of Wedekind’s most successful plays, second only to Spring Awakening in number of performances and to The Tenor (Der Kammersänger) in number of productions on the German stage, though from the end of the First World War and on through the 1920s its sequel, Pandora’s Box, exerted greater appeal. Pandora’s Box was first seen in closed performances in Nuremberg (1904) and in Vienna (1905) in a production staged by the Austrian satirical writer Karl Kraus, with Tilly Newes as Lulu and Wedekind as Jack the Ripper. Occasional open performances began to take place from 1911, and, when these were officially permitted in 1918, the play became a succès de scandale and thus a box-office success. The 1920s image of Berlin owes much to it.

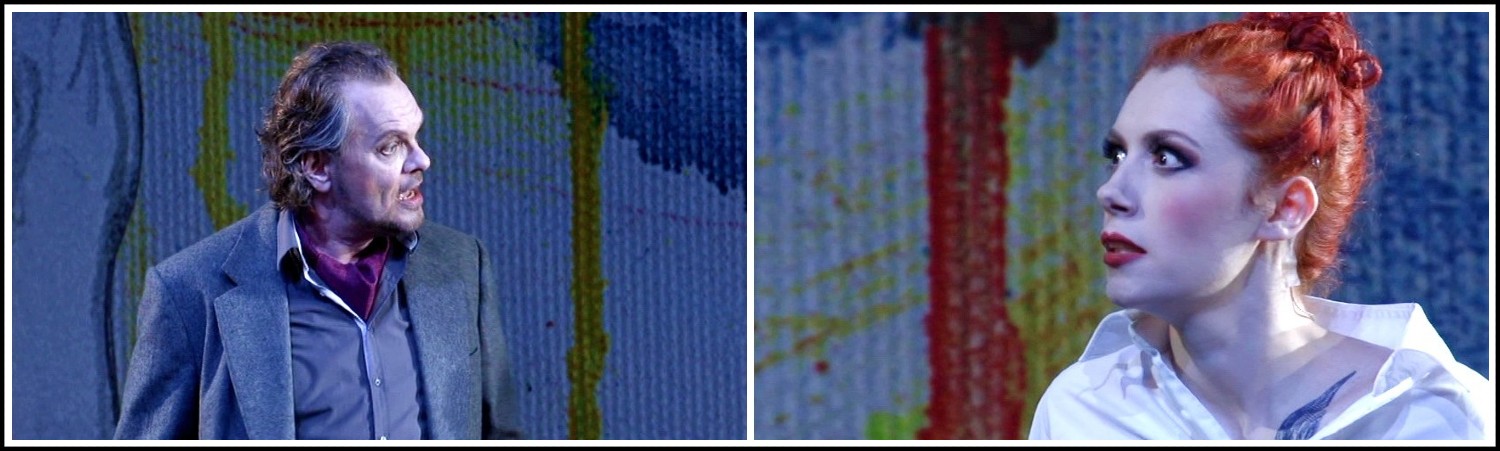

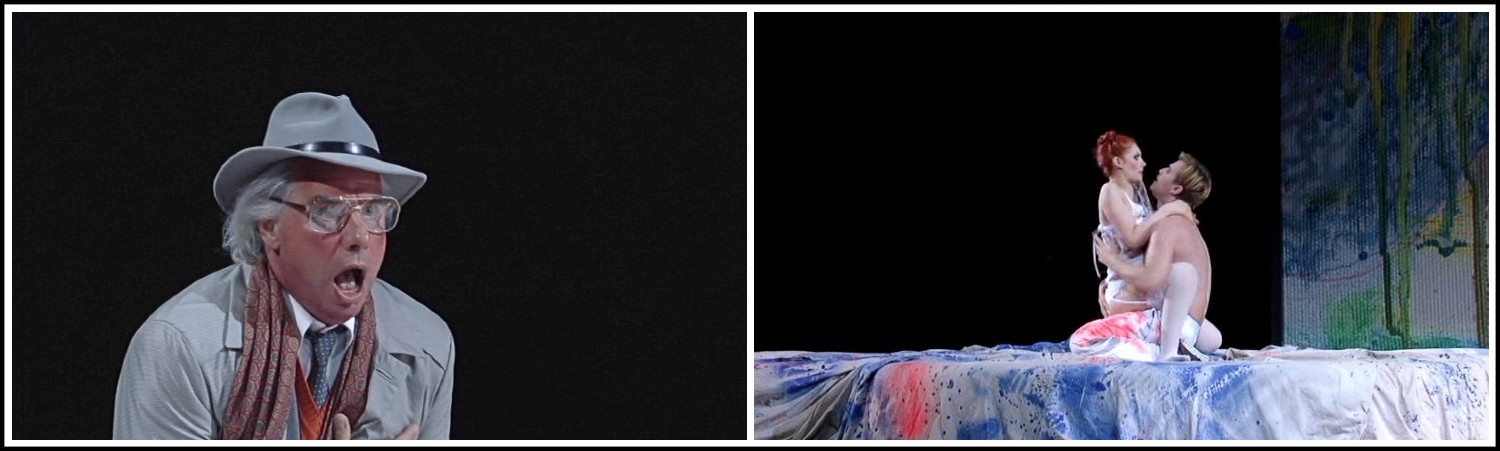

Alban Berg, Lulu, Patricia Petitbon | Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

Wedekind intended the two plays to be seen as dramas drawn from life—not literally, in the ‘photographic’ way associated with the Naturalist movement, but in such a way that, if audiences were really honest with themselves, they would recognize Lulu’s world as a valid dimension of their own as seen through the eyes of a creative writer with a strong sense of his own personal viewpoint and with a highly developed sense of stagecraft. Wedekind’s distribution of light and shade, like the emphasis he places on some episodes and themes and his discretion or indeed indifference regarding others, create a skillfully coordinated sequence of dramatic pictures portraying a world which has now largely vanished. That world can be identified quite explicitly from the text; indeed, it is important to get it into focus right from the start. Otherwise interpretations can easily get out of hand and forfeit Wedekind’s unobtrusive yet authentic grasp of reality.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Patricia Petitbon & Pavol Breslik | Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

The action of the two Lulu plays takes place between 1870 (news of the Paris Commune breaks in Act II of Earth Spirit) and 1888-89, when Jack the Ripper was perpetrating his spine-chilling murders in London—Lulu comes to a sticky end as one of his many victims. Though Wedekind generally avoids topical allusions to Germany, it is clear that Lulu’s career coincides with the reign of Wilhelm I and the Chancellorship of Bismarck. We first meet her during the economic boom, the so-called Gründerzeit, which followed the Franco-Prussian War and created a self-confident new plutocracy in Germany. Capitalism began to dominate public life at this period and to penetrate the public mind at all levels of society; men worked hard to acquire wealth and to improve their social station, and were not afraid to show off their success. The type is caught to perfection, yet humanized with individual traits, in Dr Schön, the dominant male character in Earth Spirit. Dr Schön is the proprietor and editor of a newspaper, and the mastermind behind a rapidly expanding press and business empire, a man who can afford the risk and luxury of having the lovely Lulu as his mistress.

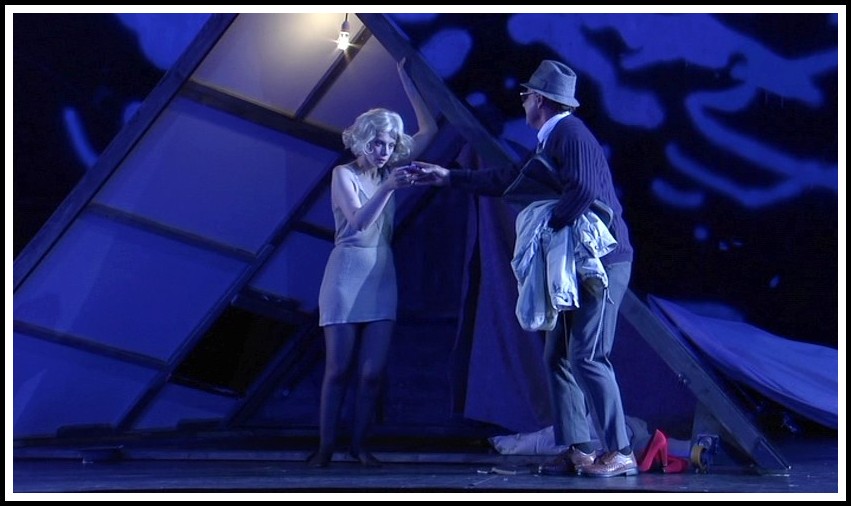

Alban Berg, Lulu, Michael Volle & Patricia Petitbon | Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

The period was one when successful artists were not only the social equals of those who employed their services as portrait painters, but also able to make fortunes never dreamt of before. There is therefore nothing incongruous in the easy relationship between Dr Schön and Lulu’s second husband, the artist Schwarz, nor in the deal struck between them after the sudden death of Lulu’s first husband, Dr Goll. ‘You married half a million,’ Schön reminds Schwarz three times in the chilling scene (II.iv) during which he remorselessly destroys the illusions under which, true to German Romantic type, the ‘otherworldly’ artist has been living. Germany had established itself as a major cultural nation during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and the increasingly affluent German middle class believed by the 1870s that it possessed a monopoly of culture. They enjoyed their sometimes misplaced patronage of the arts, and it was important to their self-esteem to appear cultured and well-read.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Pavol Breslik & Michael Volle | Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

It was at this time that the characteristically German forms of address, such as ‘Herr Doktor’ (indicative of a postgraduate academic education), were becoming accepted as social assets, along with their feminine forms, such as ‘Frau Doktor’, which applied to the wives of men with postgraduate degrees. When the play opens, Lulu is the wife of a well-to-do physician called Dr Goll; in Act II scene ii, when she first appears, Dr Schön kisses her hand as befits a lady and addresses her as ‘Frau Medizinalrat’, indicating that she is the consort of a doctor. Some minutes later, the artist Schwarz betrays his humbler origins by going one further and addressing Lulu as ‘Frau Obermedizinalrat’: the addition of that extra ‘Ober’ is a neat touch, easily overlooked, which betrays acute social observation and a naughty satirical eye. Wedekind’s plays are full of such delights. The insistence on titles and forms of address at the start of the play, together with the lifestyle that goes with them, establishes a social framework for the action and gives Lulu a social status in relation to which her later decline and fall can be measured.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Michael Volle, Thomas Piffka, Patricia Petitbon, Pavol Breslik | Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

Initially, Lulu’s standing conveys substance and respectability. But her respectability is as superficial as her substance is recent. Behind his appearance of distinguished sobriety, Dr Goll turns out to be an elderly roué to whom Schön has married Lulu in order to ensure himself easy access to her and provide her with a fortune and a foothold in society. In fact, Frau Medizinalrat Goll is none other than the girl he picked up off the streets when she was selling flowers in front of the Alhambra Café, and whom he made something of—or corrupted, depending on one’s viewpoint.

Alban Berg, Lulu, ‘Dr Goll’, Patricia Petitbon, Pavol Breslik | Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

Wedekind’s Lulu plays are as serious in intention as the social plays of Hauptmann and Schnitzler, and their texts are rich in hints and allusions which indicate his powers as an observer of the behaviour and values of his contemporaries. If ‘social drama’ seems a misnomer to many admirers and modern producers of the play, this is probably the result of Wedekind’s preference for self-contained and often meticulously worked-out episodes, rather than for the sustained continuity of action and argument associated with the type of social drama which Ibsen and Hauptmann, and Chekhov too, had perfected. The dissimilarities between the two approaches become even more evident in Pandora’s Box, where the setting shifts from the late Dr Schön’s solid, well-appointed German villa (the scene of the last act of Earth Spirit) to an opulent Paris salon reminiscent of the demi-monde of La Dame aux camélias, and then, finally, to a damp and sordid garret in London, three settings which graphically convey the stages in Lulu’s progress and downfall.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Patricia Petitbon | Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

From start to finish, from Frau Medizinalrat Goll to London prostitute, the arc of Lulu’s career is subtly accompanied by the presence of her portrait, to which Schwarz is putting the finishing touches as Earth Spirit opens. Lulu’s portrait is a fine example of the key function a stage prop can have in a modern drama, and any production blind enough to overlook it misses a vital dimension—the implicit contrast it constantly suggests between then and now. To ignore this dimension is to falsify Wedekind’s conception, because it is precisely by such means that he realizes it in theatrical terms.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Tanja Ariane Baumgartner, Franz Grundheber, Patricia Petitbon | Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

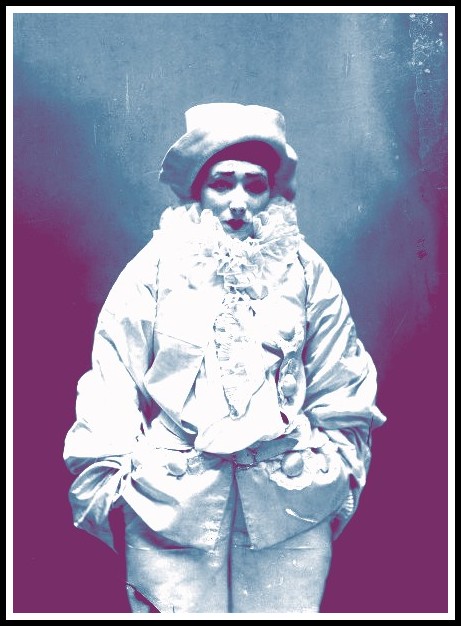

Lulu’s portrait relates to her like that of Dorian Gray to him, but in reverse: it remains young while she grows old (Wilde’s novel appeared in 1891, and its German translation in 1901). It also links up with the craze for Pierrots which swept through all levels of society from the pier pavilion to French avant-garde poetry in the 1890s. Naïve, comic, yet also pathetic, the Pierrot figure was associated with wordless mime which conveyed its childish joys and sudden despairs; Lulu’s portrait as a Pierrot enabled Wedekind to remind audiences throughout the drama of her essential vulnerability. She is of course the central figure in both plays and the pivot of the action, but she never says very much, and what she says is hardly memorable. Yet she holds our attention as spectators, just as she holds that of the men in her life, by simply being what she is. How right it was of Schwarz to paint her as a Pierrot, with its connotations of pretty doll and puppet. The Pierrot image added a visual dimension to the drama which can still appeal, but which was more heavily laden with associations and richer in suggestive power for audiences in Wedekind’s own day.

Nadar, Sarah Bernhardt as Pierrot, 1883

Only in Act II of Earth Spirit is the portrait absent. Maybe Wedekind had forgotten its sustained symbolism when he added this act to his original ‘monster tragedy’ in order to publish its first half as a self-contained drama. But its absence is more likely to be deliberate, for here, where Schön is trying to promote Lulu as a star on the professional stage, we feel that her pretty costumes are a disguise which does not really suit her. Nothing comes of the artistic career on which her patron tries to launch her; her true nature finds expression in other ways. Wedekind’s chief claim to fame in dramatizing her story is that he gave tangible form to one of the twentieth century’s potent myths, the woman sex-symbol in an amoral world.

Christine Schafer, Pierrot lunaire, Schoenberg

The portrait not only provides effective contrast to Lulu’s changing situation from act to act; its frames and settings also function as visual correlatives to the ways in which she is treated by the men who take her up, and to the differing images they have of her. It is surrounded by artistic extravagance by Schwarz, the successful society painter; by reproduction gilt by Dr Schön, the prosperous self-made man. After Lulu has killed him, been convicted of his murder, and been rescued from prison by Countess Geschwitz, it is set into the wall of a luxury apartment, like a safe: Lulu has become little more than a lucrative commodity for others to deal in. Her chains may be golden ones, but they restrict her freedom all the same, as she bitterly recognizes when the white-slave dealer Casti-Piani offers her the stark choice between being an ex-convict or a courtesan, and proposes to negotiate a career for her in an exclusive Cairo brothel. By the end, in London, when she is struggling to survive and about to meet her bloody fate at the hands of Jack the Ripper, her image is being lovingly preserved, rolled up, by her devoted friend the Countess; the only other people still around to admire it are the mysterious Schigolch, her so-called father, and Dr Schön’s son Alwa.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Thomas Johannes Mayer & Patricia Petitbon | Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

To most of the men in her life Lulu is the embodiment of private fantasies and the fulfilment of private wishes. While she makes what she can of herself in a mercenary society and then struggles to keep herself going in a cruel world, her men in their various ways regard and treat her as a gratifying escape from it, though they also sometimes realize more or less clearly that she presents a constant threat to the constricting social order they have constructed for themselves. We should never forget that pre-WWI society was Wedekind’s particular bête noire even in the Lulu plays, where it seems at first sight that erotic beauty is the destructive force that excites his wrath. Each man in Lulu’s life seeks and finds in her what he wants or needs; but in none of them (except perhaps Dr Schön or, arguably, Jack the Ripper) does she find anything comparable. Each lets her down because he is flawed by a blind disregard for her true self, an indifference that stems from that blend of self-centredness and self-interest which Wedekind saw as typically male and which Lulu’s partners never question because it is an integral part of the conventional thinking of their male-dominated society.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Patricia Petitbon & Michael Volle | Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

To most of the men Lulu’s sex appeal is her sole raison d’être. For the elderly Dr Goll it provides titillation; for Schwarz, artistic inspiration, while glamour and pleasure are what Dr Schön sees and finds in her. But each tends to call her by pet names of his own invention, and to forget who she really is. Who is she really? Does even her old ‘father’ Schigolch really know? Perhaps she is just an emanation of the life-force (a concept much in vogue at the time) or a symbol of instinctual human joy whose flirtations with a series of egocentric individuals are simply part of the natural process, a dance of life as well as death. Only the Countess thinks differently, and she alone is selfless. But the drawback, of course, is that Lulu is not drawn to her. ‘Damn!’ says the Countess as she, too, dies. It is the drama’s last word, and with it horror and comedy meet in rare conjunction.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Tanja Ariane Baumgartner | Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

The Lulu plays are a perplexing labyrinth, and much hot air has been vented on their meaning and significance. In their historical context, they make sense as a seminally productive variant of social realism in which axe-grinding earnestness and token verisimilitude are triumphantly replaced by unabashed theatricality.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Patricia Petitbon & Michael Volle | Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

The imagery of their central stage property, Lulu’s portrait, provides a cluster of thematically interrelated elements which give unity, but a unity subtle and elusive enough not to impair the feeling they convey of the sheer arbitrariness of ‘real life’. Comic elements and farcical episodes abound in both plays, and, as in Restoration comedy, sex naturally provides the animating force and momentum underlying the playwright’s burlesque treatment of the way the world treats a lovely woman.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Patricia Petitbon & Michael Volle | Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

But the Lulu plays have a tragic quality about them, too, which is probably easier to appreciate nowadays, when tragic ideals and aspirations have been tempered and deflated by the theatres of cruelty, silence and the absurd. Whatever the circumstances—and in the Lulu plays they are often ludicrous, risqué or even vulgar—the wanton destruction of something beautiful and intensely alive must always have a tragic impact. At the end of Pandora’s Box the stage is as littered with corpses as in any Jacobean tragedy or grand guignol melodrama. Goll, Schwarz and Schön are dead already, and now Alwa is slain by Lulu’s black London client, Chief Kungu Poti…

Alban Berg, Lulu, Patricia Petitbon, Pavol Breslik, Thomas Piffka | Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

…while Lulu and the Countess end up the Ripper’s victims.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Tanja Ariane Baumgartner, Patricia Petitbon, Michael Volle | Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

The sole survivor is old Schigolch, who is in many ways the most fascinating male figure in the plays. He first appears in Act II of Earth Spirit, when Schwarz mistakes him for an itinerant beggar. From the start there is an other-worldly air about him, though he may appear to be just an old blackguard. Destined to outlive them all, he tells Lulu at the very beginning that he is near unto death, and reminds her that ‘we are dust’. In Act IV scene v, Rodrigo, the ‘strong man’, toasts him as ‘Gevatter Tod’ (Old Father Death) just after Lulu (in the preceding scene) has confessed her lifelong fear of death to Schön. Schigolch’s allusions to mortality and decay take on wider dimensions in the closing scenes of Pandora’s Box, where his talk reverts to the need for light amidst the gathering gloom—for, without Lulu, the light has gone out of the world.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Patricia Petitbon & Franz Grundheber | Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

What of Lulu herself? Like her admirers in the drama, critics see her in many different lights. To some she is predatory and destructive, to others vulnerable and naïve. She has been described as fascinating and as repulsive, the amoral embodiment of sexual instinct, a female Don Juan, an innocent corruptress of decent social standards, a vamp, a spoilt child, a sort of doll—or a courageous woman who lives life on her own terms, but falls victim to a rapacious, violent, male-dominated society. She may be some or, indeed, all of these things; the emphasis has always varied from actress to actress, from production to production. But she may also be more besides, as the titles of the two plays suggest. She may be an incarnation of the life-force and the embodiment of all that men’s senses crave; the eternal object of the sexual urge; the irresistible personification of earthly joys as well as an ordinary woman. Is she Eve, the mother of all our sins and Adam’s undoing? Or is she Pandora, according to classical mythology the first woman ever created, whose heart the gods filled with perfidy and lies, and who brought with her into the world a mysterious box which held countless afflictions for the human race? Wedekind’s Prologue to Earth Spirit goes one step further, and equates Lulu with the serpent in the Garden of Eden, ‘created for every abuse, to allure and to poison and seduce’.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Patricia Petitbon & Michael Volle | Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

Lulu must certainly be seductive. The role is one where personality and appearance are at a premium, for if a Lulu fails to convince her audience that she is irresistible, the drama collapses. Most of the time she is the only woman on stage, and most of the other characters define themselves almost entirely through their responses to her; neither she nor they have much to fall back on by way of other interest or motivation. But her beauty and her sex appeal lie in presentation rather than in the words of the text, which are colourless and flat, little more than an all-purpose script which requires much extraneous and simultaneous detail to fill it out before the role can be fully realized.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Patricia Petitbon & Thomas Piffka | Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

In this respect Wedekind is in marked contrast to Hauptmann or Schnitzler, who both excel in capturing and conveying mood and motivation through the speech of their characters, especially when their plays are set in the sociolinguistic locations they knew best. Wedekind did not possess their ear for the psychological dimensions of spoken language. Perhaps because he grew up in dialect-speaking Switzerland, he was not as attuned as they were to the idiomatic subtleties of modern German as spoken by people in Austria and Germany. This may have been something of a disadvantage, yet it also gave him one distinct advantage: his work loses much less in translation than theirs, which in turn may well account for the relatively greater success he has enjoyed abroad.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Thomas Piffka & Patricia Petitbon | Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

Thematically the Lulu plays do have their parallels in the work of Hauptmann and Schnitzler. The comparison with The Round Dance is telling. The male characters in the Lulu plays have counterparts of sorts in the Schnitzler play, since it was the aim of both dramatists to include all sorts and conditions of men; the obvious difference is that in Schnitzler’s play the ‘eternal feminine’ is forever re-embodied in well-differentiated individual women, whereas in Wedekind’s it is concentrated in the protagonist, who therefore has to be all things to all men. Closer to Wedekind’s conception is Hauptmann’s play And Pippa Dances! (1906), which was written for and inspired by Ida Orloff, a talented young actress who had already appeared in a minor role in the 1905 Vienna production of Pandora’s Box. Hauptmann became enthralled by her when he saw her ‘become’ his own imaginary character Hannele. Pippa, the role he wrote for her, represents the ideal of elusive femininity to an assortment of men, but, in order to pursue this theme without actually implying that all women are really the same, Hauptmann soon diverges from both Wedekind and Schnitzler by leaving the plane of common reality behind and entering a fantasy world in which poetic licence is permissible and symbolism can weave its spells unhindered.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Patricia Petitbon | Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

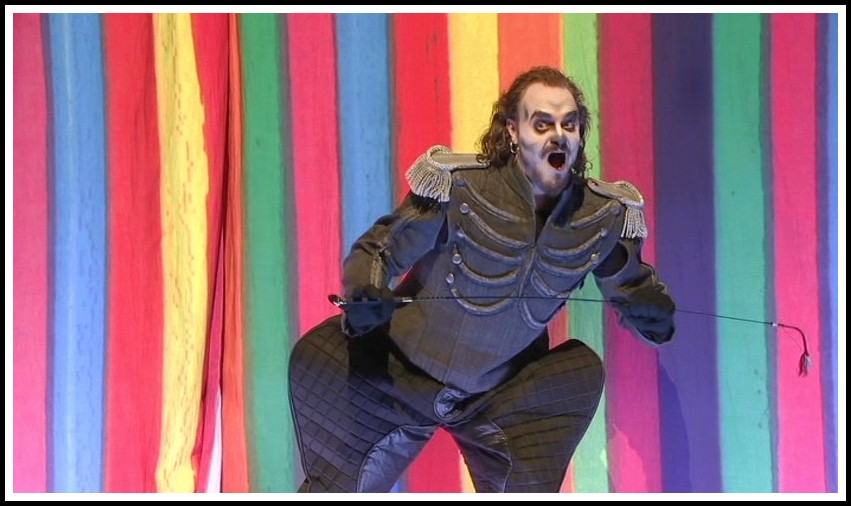

The all-purpose, almost ‘acquired’ feel of Wedekind’s language, together with the ease with which his text can be adapted and pruned, have undoubtedly stood the two Lulu plays in good stead in the theatre. Though he gave them a framework of topical allusions, updating is no great problem and demonstrates the drama’s continuing relevance. In Wedekind’s own lifetime, Lulu was an Edwardian or fin-de-siècle demi-mondaine; in the 1902 Berlin production Gertrud Eysoldt presented her as a soulless, sophisticated modern version of Salome; in Vienna in 1905 Tilly Newes, later to become Wedekind’s wife, brought out her latent tenderness and femininity; while, a little later, Maria Orska’s Lulu was the white-faced Pierrot doll. Then, in 1928, G. W. Pabst’s silent film Die Büchse der Pandora allowed Louise Brooks to project an image of Lulu 1920s style—indeed this film has led many people to assume that the plays were in fact a product of that era. Changing attitudes to women, as well as to public and private morality, have naturally resulted in shifts of emphasis, and this is reflected in more recent stage interpretations. The circus element, with Wedekind as ringmaster and Lulu as tamed beast, present in the Prologue but only very intermittently in the main text, has inspired some productions, while others have brought out the elements of burlesque and farce which do indeed gain the upper hand at various points even in the original text.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Patricia Petitbon & Michael Volle | Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

Are the Lulu plays a closely structured period piece? Or is Wedekind’s text an open invitation to experimentation and reinterpretation? At one point Wedekind claimed, rather tongue-in-cheek, that the lesbian Countess was the true tragic heroine of the plays; if enough of the text is cut, no doubt the second play can be presented successfully even in this way. Given pace, zest, colour, movement, good ensemble, and a wild and lovely actress in the title role, there is no doubt that Wedekind’s masterpiece still works and can prove itself to be a winner.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Tanja Ariane Baumgartner & Patricia Petitbon | Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2024 | All rights reserved

Comments