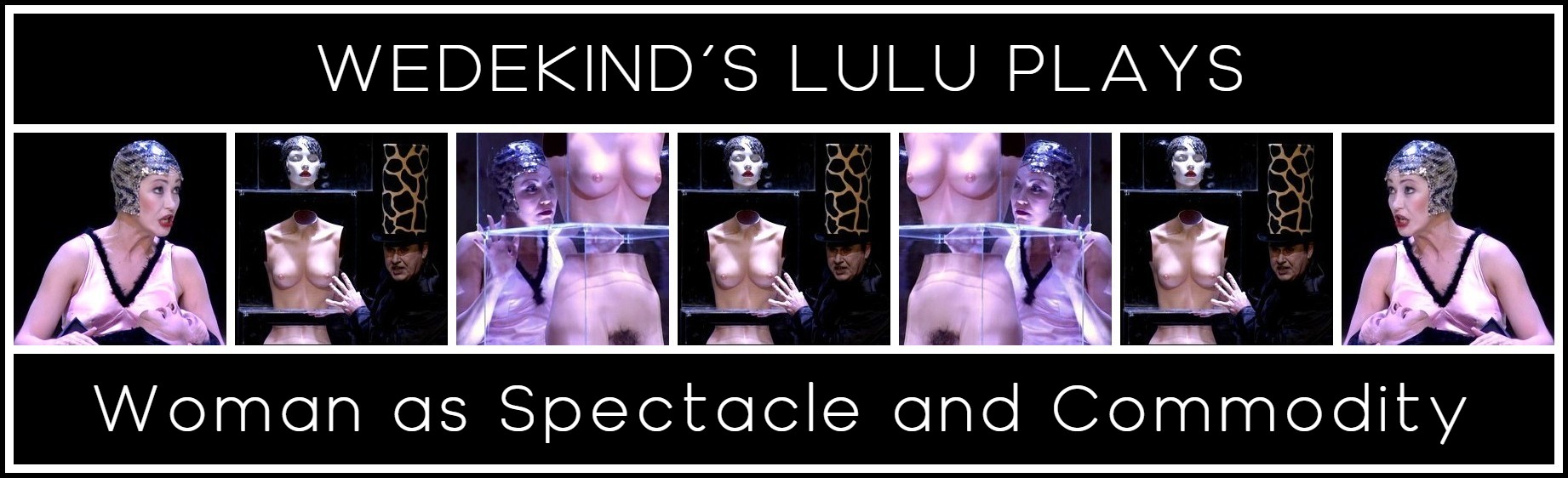

Demythologizing the Femme Fatale

WEDEKIND’S LULU PLAYS: WOMAN AS SPECTACLE AND COMMODITY

Gail Finney

Posted by kind permission of Gail Finney, Professor Emerita of German and Comparative Literature, University of California, Davis

From Gail Finney, Women in Modern Drama: Freud, Feminism, and European Theater at the Turn of the Century

(Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1989) pp. 79-101

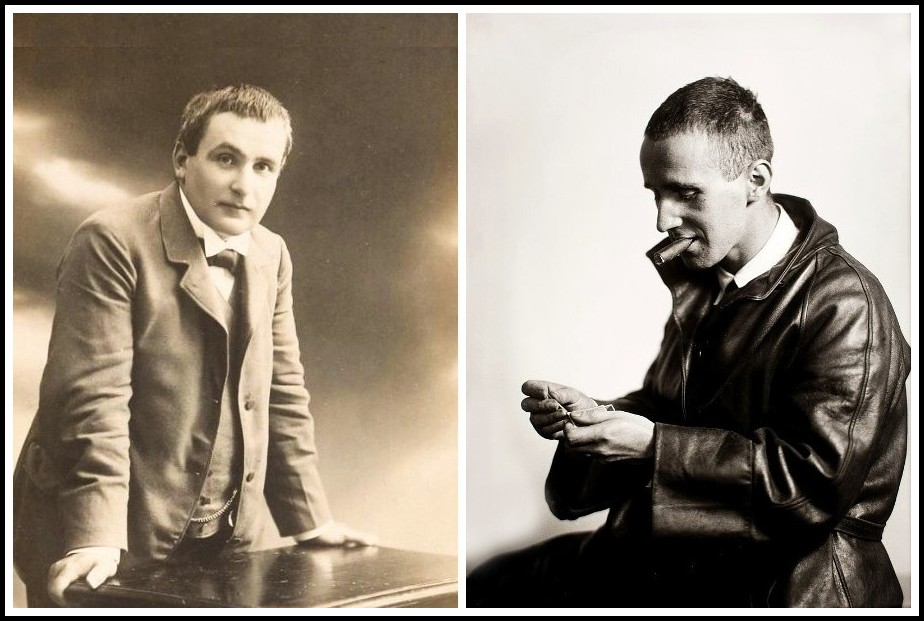

Scarcely anyone in the history of German literature has provoked such mixed and violent reactions as Frank Wedekind, self-styled bohemian and passionate nonconformist. In stark contrast to the respectable physician Schnitzler and even to Wilde, who though also an enfant terrible of the literary world never relinquished the trappings of high society, Wedekind punctuated his work in advertising and journalism with stints as an actor and cabaret singer, spent one of the happiest periods of his life in the company of Parisian circus performers, and served a six-month prison term for ‘libeling the crown’ in one of his political poems. Little wonder, then, that Brecht was moved to comment after Wedekind’s death in 1918 that ‘his greatest work was his personality.’ Looking back with the hindsight that Brecht could not have, we recognize the degree to which his observation obscures the enormous impact Wedekind was to have on Brecht himself and on the many other twentieth-century dramatists whose work would be very different without his example.

Frank Wedekind & Bertolt Brecht

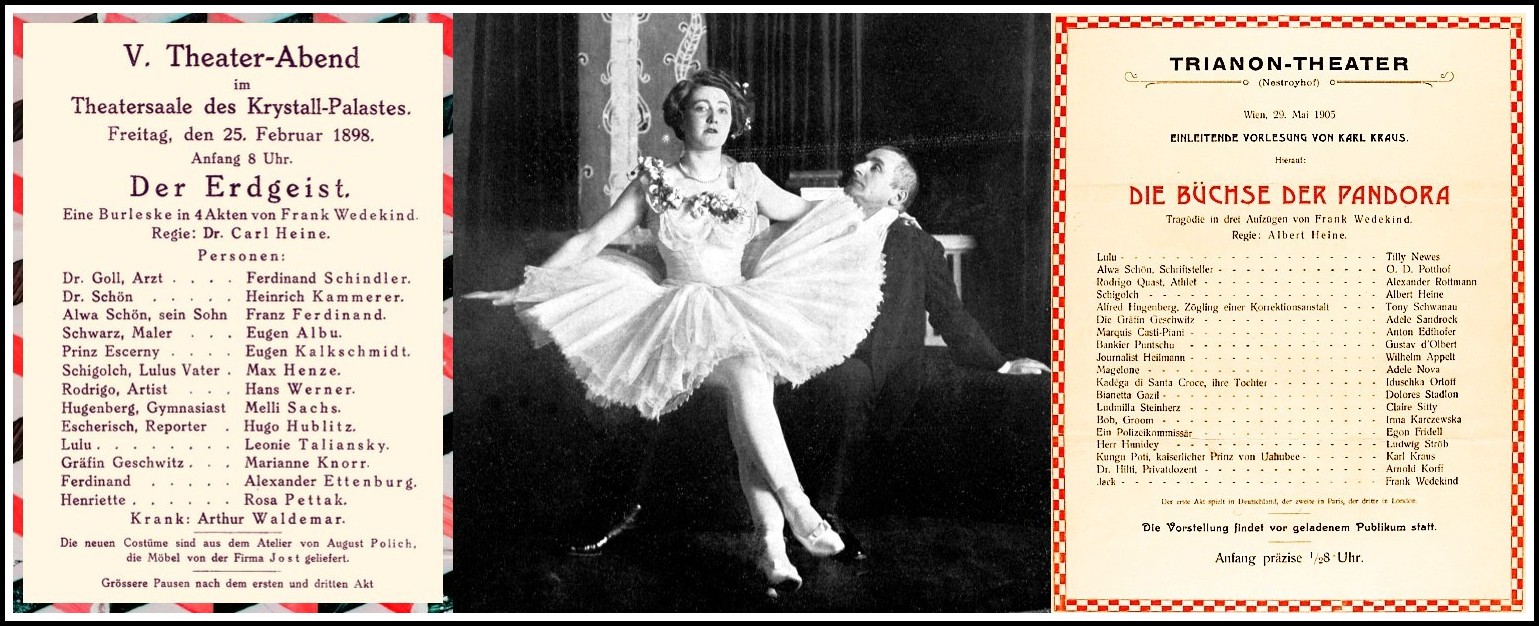

None of Wedekind’s dramas has been more influential than his so-called Lulu plays, which in their unusual mixture of satiric, grotesque, and tragic elements combine some of the most memorable features of naturalist and symbolist theater and also anticipate expressionism. Wedekind’s initial inspiration for the subject was twofold: the circus pantomime Lulu, Une Clownesse danseuse by Félicien Champsaur, which he saw at the Nouveau Cirque in Paris in the early 1890s, and the stories of Jack the Ripper, whose notorious sex murders in London a few years before had sent shock waves across half of Europe. The Lulu material occupied Wedekind longer than any of his other works, off and on from 1892 to 1913. Because the original drama of 1895 was unwieldy, he expanded it and broke it up into two plays, Earth-Spirit and Pandora’s Box. Although Earth-Spirit was produced in various German cities from 1898 on, attracting directors of such renown as Max Reinhardt, Pandora’s Box fell victim to the censor’s knife, and it was not publicly performed in Germany until after the abolition of censorship in 1918. Although Wedekind was admired by intellectuals, as Brecht’s tribute to him attests, throughout his life the general public and popular press tended to regard him as little more than a pornographer.

Der Erdgeist (poster for 1898 production) | Tilly & Frank Wedekind | Die Büchse der Pandora (poster for 1905 production)

The main cause of the scandal surrounding the Lulu plays was the figure of the heroine herself. Responsible for the deaths not only of three husbands but of several admirers and possibly of the wife of her third spouse, Schön, as well, Lulu appears to be a virtual caricature of the femme fatale. Like Wilde’s Salomé, she is a fin-de-siècle incarnation of an ancient myth; like the biblical Salomé, the mythological Pandora, created to punish mankind for Prometheus’ theft of fire from the gods, is both beautiful and a source of evil, reflecting the fundamental and persisting ambivalence of men toward the female sex. As the titles of both Lulu dramas suggest and as the animal tamer who introduces her in the prologue to Earth-Spirit expressly states, Lulu is intended to represent ‘the primal form of woman.’ Perhaps it was the work’s evocation of this mythic, primal realm, the source of so many operas, that inspired Alban Berg in the 1930s to follow Strauss’s example with Salome and compose his Lulu, a combined version of the two plays which has become a mainstay of opera repertory. Whatever the case, whether Lulu is seen as the manifestation of an ‘unconditional moral imperative’ or as ‘consisting of nothing but flesh and vulva,’ she has traditionally been equated with nature, instinct, animality.

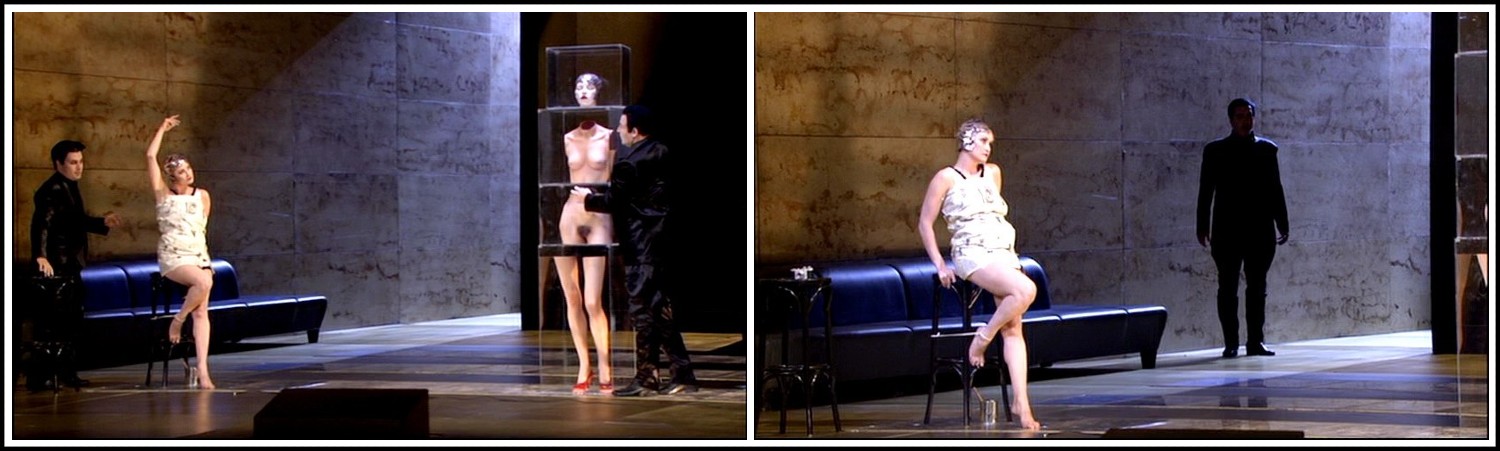

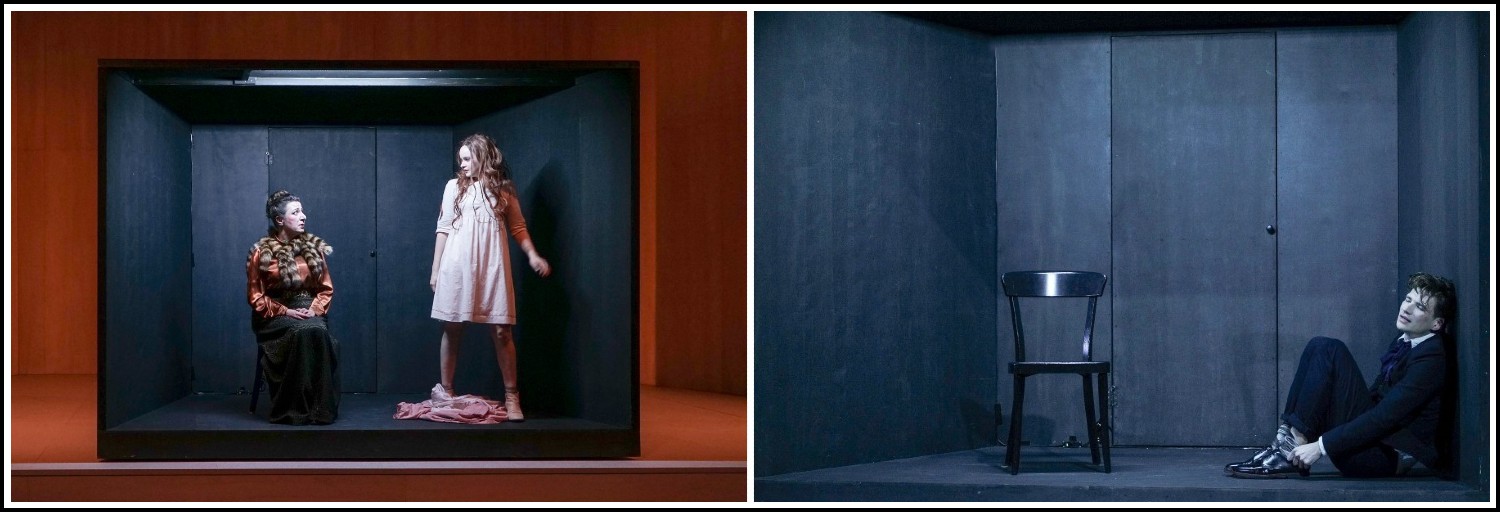

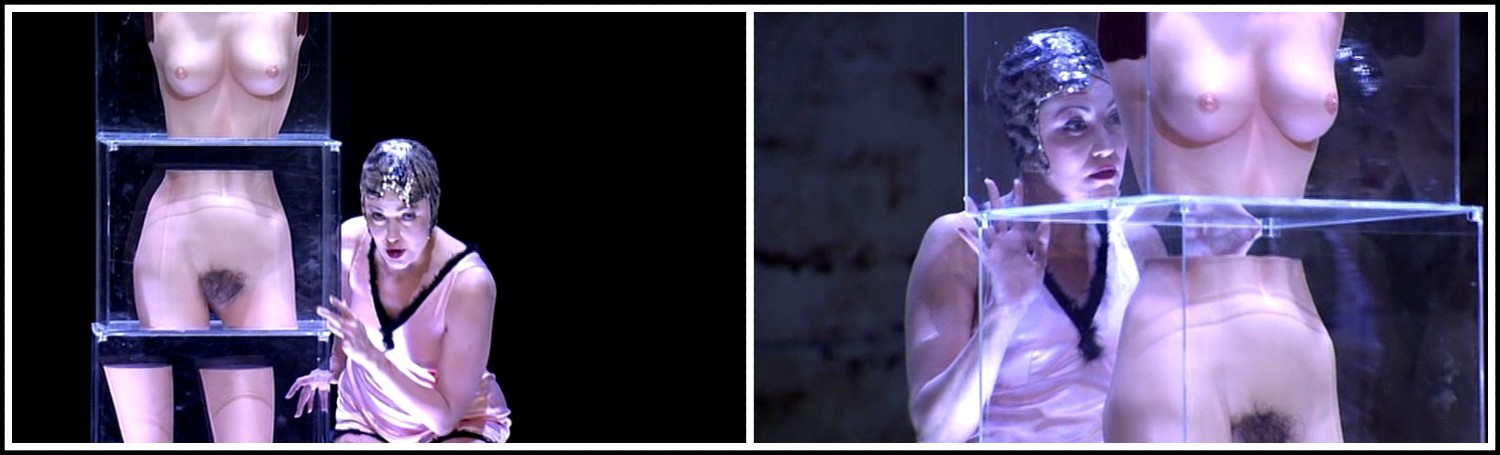

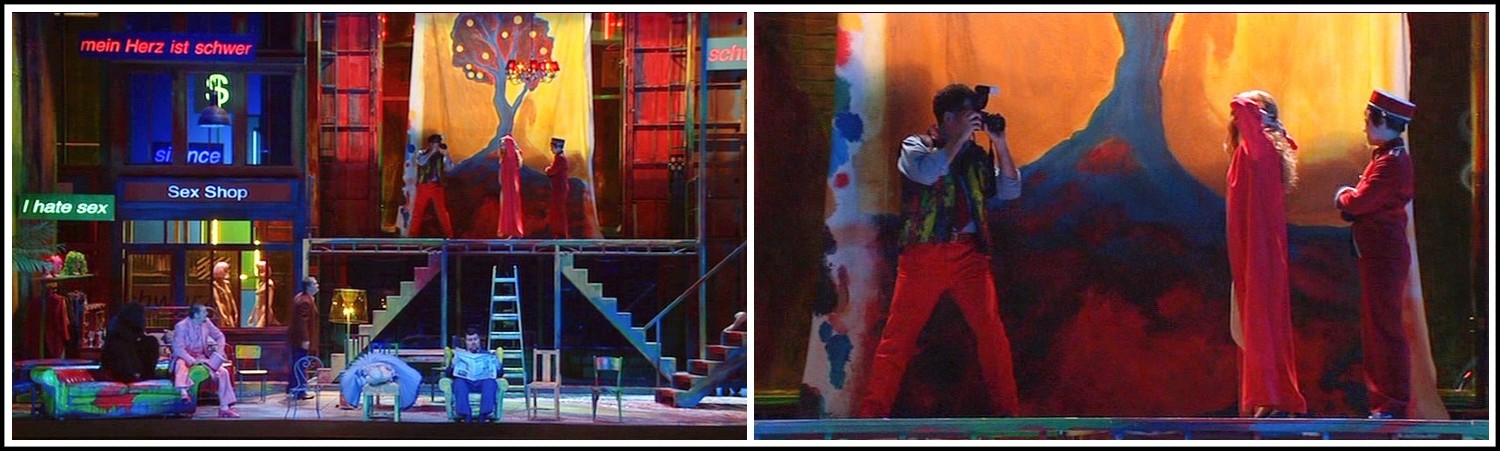

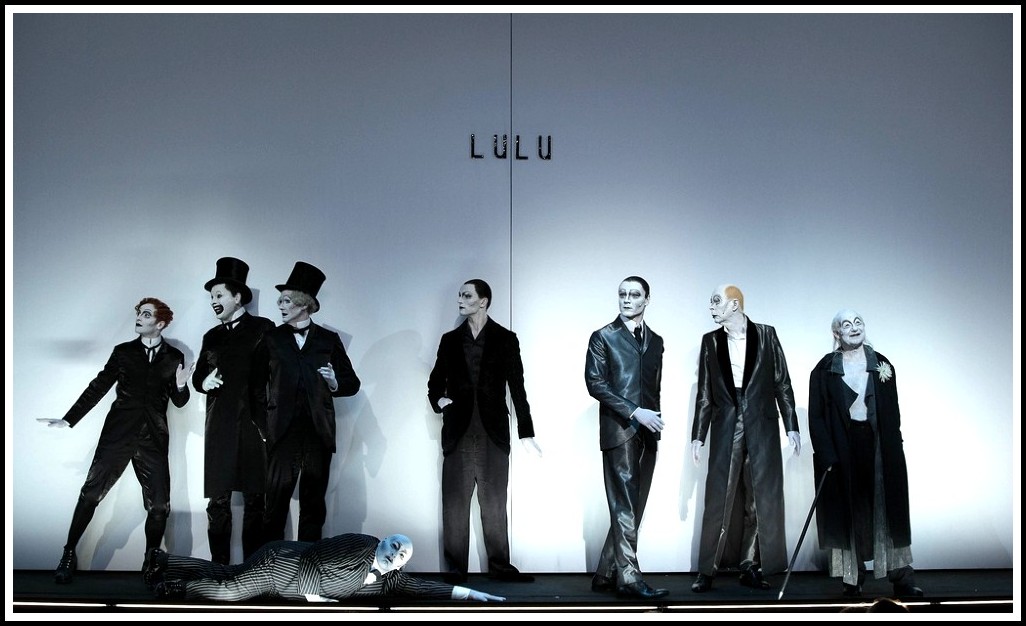

Alban Berg, Lulu, Rolf Haunstein (Animal Tamer) | Zurich Opera House, Franz Welser-Möst, 2002

Silvia Bovenschen has shown how this conception of Lulu as natural phenomenon is a paradigmatic example of male myths of the feminine. Yet this perspective does not fully take into account the extent to which Wedekind depicts the character Lulu as both a product of her society and a quintessential incorporation of its values. For Earth-Spirit and Pandora’s Box offer one of the fullest portrayals in dramatic literature of the cultural construction of a woman into spectacle and commodity, two roles conventionally played by women in consumer economies. Far from being removed from the workings of her society—Wilhelmine Germany undergoing a belated industrial revolution—Lulu reveals the ways in which its dominant ideologies of patriarchy and capitalism reinforce each other as mechanisms of objectification. Just as Salomé’s wanton behavior toward Jokanaan is conditioned by her stepfather’s lustful treatment of her, Lulu is not simply born but made, shaped by her particular upbringing and education.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Laura Aikin (Lulu) | Zurich Opera House, Franz Welser-Möst, 2002

For writers in the German literary tradition from Goethe to Thomas Mann, perhaps no theme has been more central than the importance of education—Bildung—in human development. Wedekind is no exception. The prelude to one of his first plays, Die junge Welt,1 satirically depicts the restrictive education received by girls at the turn of the century; the farce Fritz Schwigerling2 and the novel fragment Mine-Haha oder Über die körperliche Erziehung der jungen Mädchen (1901) present detailed pedagogical programs, emphasizing especially the importance of physical fitness in the upbringing of children.

1 – Originally published as Kinder und Narren (1891).

2 – Later retitled Der Liebestrank (1899).

Frank Wedekind, Spring Awakening, Catharina May | Theaternatur, Benneckenstein, 2018

But the most enduring treatment of education in Wedekind’s oeuvre is the early drama Spring Awakening (1891). Anticipating Freud’s ‘Sexual Enlightenment of Children’ (1907), Wedekind’s play graphically demonstrates the detrimental results of the failure to provide children with what would today be called ‘sex education’: one girl dies from the effects of a botched abortion, having become pregnant after her embarrassed mother was unable to explain to her the mechanics of reproduction, and her pubescent lover is sent to a reformatory because the illustrated description of sexual intercourse with which he enlightened a schoolmate is blamed for the schoolmate’s breakdown and suicide (in fact brought on by his failure to be promoted to the next grade).

Frank Wedekind, Spring Awakening, Katrin Lindner | SchauspielKIEL, Kiel, 2016

Despite Wedekind’s repeated stabs at the naturalist movement in general and Gerhart Hauptmann in particular, in the Lulu plays as well as in his other works he calls attention to the influence of early environment and training on the subsequent life of the adult. The question posed to the judge at Lulu’s murder trial by her teenage admirer, Hugenberg (aside from Countess Geschwitz, he is the only character in the two dramas with what might be called a soul), should not be overlooked: ‘How can you tell what would have become of you if as a ten-year-old child you’d had to knock about barefoot at night in cafés?’. For the period of Lulu’s life to which Hugenberg refers is that spent with her first major shaping figure, or at least the first we learn about, the mysterious tramp Schigolch, who knew her ‘when all there was to see of [her] was [her] two big eyes’. Many critics have stressed Lulu’s mythical qualities and blurred origins—Schigolch’s dry observation that she ‘never had’ a father, Schön’s claim that she did not know her mother and that her mother ‘has no grave’. Less crucial for Lulu’s development than the absence of her biological parents, however, are the presence and influence of her two incestuous foster fathers, Schigolch and Schön.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Lynn Lange (Lulu as a child), Alfred Muff (Schön), Laura Aikin (Lulu) | Zurich Opera House, Franz Welser-Möst, 2002

Having first encountered Lulu as a ragged twelve-year-old making her way by petty thievery and by selling flowers on the street, Schön has always assumed that Schigolch is her father, although the text never confirms this assumption. Whereas the education provided her by the bum, pimp, and murderer Schigolch is anything but middle-class, he is far from the primeval, asocial creature that some critics have seen him to be, for example, associating his name with Molch, the German word for ‘salamander.’ Considering his character, we can derive a more appropriate reading of his name from the nearly exact equivalence of its inverse with logisch, the German for ‘logical.’ For Schigolch is nothing if not a shrewd thinker, managing to survive without a job by living outside the law and teaching Lulu to do the same, as her attempt to steal Schön’s watch as a child demonstrates. As important to Schigolch as money is sex. Even in his old age he comes begging to Lulu for funds to support his mistresses, and in the midst of his and Lulu’s desperately impoverished circumstances in London at the end of Pandora’s Box he is preoccupied with trying to seduce the keeper of a nearby pub. A number of remarks Schigolch lets fall, such as his admission that he, like so many others, originally wanted to marry Lulu, suggest that the erotic relationship between them began when she was a child. And his powerful sexuality doubtless influenced her by its example, just as Herod’s does his stepdaughter Salomé in Wilde’s play.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Laura Aikin (Lulu) & Guido Götzen (Schigolch) | Zurich Opera House, Franz Welser-Möst, 2002

In their attention to the eroticism in the relationships of Salomé and Lulu with their father figures, Wilde and Wedekind dare to explore terrain from which Freud shied away. Freud initially postulated that the hysteria of many of his female patients was the result of sexual advances made by their fathers, but he later rejected this ‘seduction theory’ in favor of the view that his patients’ revelations were simply sexual fantasies. In recent years much debate has centered on the question of whether Freud abandoned the seduction theory because of contrary evidence or simply because he was reluctant to expose such shocking facts to the world and feared the professional opposition that his disclosure would arouse. Whichever the case, his thoughts on the subject were later incorporated into his writings on infantile sexuality and the Oedipus complex, and he never gave up his belief that ‘the number of women who remain till a late age tenderly dependent on a paternal object, or indeed on their real father, is very great.’

Alban Berg, Lulu, Lynn Lange (Lulu as a child), Laura Aikin (Lulu), Alfred Muff (Schön) | Zurich Opera House, Franz Welser-Möst, 2002

Wilde’s and Wedekind’s metaphorical treatment of father–daughter attraction (involving not biological fathers but rather step- or foster fathers) shows the degree to which such ideas were in the air at the time. That they were not only in the air but also realized is very likely, especially in light of recent work on incest. Seeking to explain the overwhelming predominance of father–daughter incest in Western societies, Judith Herman and Lisa Hirschman observe: Although custom will eventually oblige the little boy to give away his daughter in marriage to another man (note that mothers do not give away either daughters or sons), the taboo against sexual contact with his daughter will never carry the same force, either psychologically or socially, as the taboo which prohibited incest with his mother. There is no punishing father to avenge father–daughter incest. A patriarchal society, then, most abhors the idea of incest between mother and son, because this is an affront to the father’s prerogatives. Though incest between father and daughter is also forbidden, the prohibition carries considerably less weight and is, therefore, more frequently violated. This observation sheds retrospective light on the prevalence of the theme of father–daughter incest in the works of Wedekind and his contemporaries.

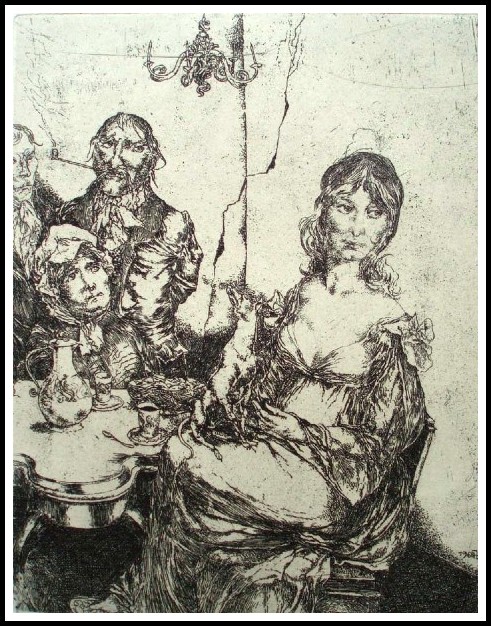

Heinz Zander, Die Marquise von O…, 1968

In contrast to the children in Spring Awakening, the young Lulu suffers not from a lack but from an excess of sexual knowledge. Her most significant lesson at the hands of her sexual educator Schigolch is her entrance into the world of prostitution, an initiation he reveals to us with his comment, in the last act of Pandora’s Box, that it was as difficult for her to take to the streets twenty years before as it is now. (The corruption of Lulu is satirically echoed in the second act of Pandora’s Box in the fate of the twelve-year-old Kadidja, whose mother introduces her to wealthy older gentlemen who lust for her and, after the Jungfrau [‘virgin’] shares that support them have become worthless, decides to take her out of school and let her try out for the variety theater. In introducing Lulu to prostitution, Schigolch lays the foundation in her youth for the role that she is increasingly to play in her adult life—the role of commodity, or object of exchange.

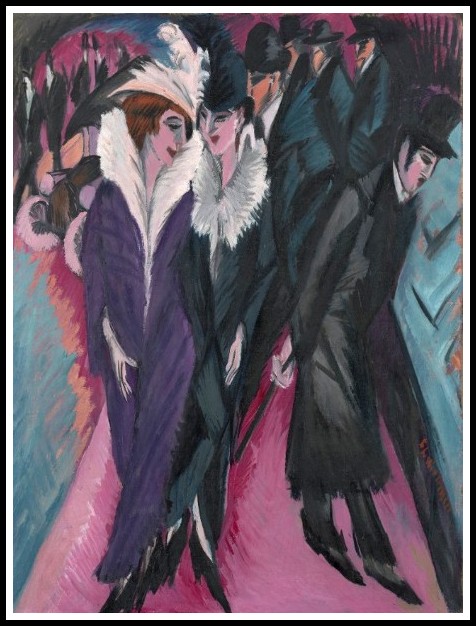

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Street in Berlin, 1913

This, then, is the product ‘snatched from the clutches of the police’ by Schön, Lulu’s second father figure: a girl familiar at the age of twelve with street theft, child molestation, and prostitution. Numerous statements call attention to his function as a shaping figure for Lulu, such as his own repeated reminders to her of the sacrifices he has made for her education; other characters also credit him with the responsibility for her development. The effects of this phase of her education are evident, for instance, in the repulsion she feels for her lesbian admirer Geschwitz, insofar as heterosexuality is the result of instinct conditioning. The period she spent with Schigolch, by contrast, had been for her one of undifferentiated sexuality, reflected in the name Lulu, used solely by him. Lulu not only is a name given to both sexes in Germany but also is akin to the bisyllabic consonant-vowel words first learned by children and associated with their earliest needs: ‘mama,’ ‘papa,’ ‘kaka,’ ‘pipi.’ When Schigolch visits Lulu at the home of her second husband, Schwarz, after not seeing her for several years, she tells him that no one has called her Lulu for ages and that the name now sounds to her ‘completely out of date’, a characterization that indicates the progress she has made under the tutelage of Schön.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Laura Aikin (Lulu) & Guido Götzen (Schigolch) | Zurich Opera House, Franz Welser-Möst, 2002

For the most part, however, Schön’s education of Lulu affects her only superficially. As a newspaperman, a controller of public opinion, an advertiser and marketer whose very name (meaning ‘beautiful’) announces his aesthetic sense, he is well qualified to mold her into a beautiful object of desire. That there is indeed little substance beneath this attractive surface is perhaps most evident in the parodied catechism put to her by Schwarz: Can you speak the truth? Lulu: I don’t know. Do you believe in a creator? I don’t know. Is there anything you can swear by? I don’t know. Leave me alone! You’re mad. What do you believe in, then? I don’t know. Have you no soul, then? I don’t know. Have you ever been in love? I don’t know. She doesn’t know! I don’t know.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Laura Aikin (Lulu) & Steve Davislim (Schwarz) | Zurich Opera House, Franz Welser-Möst, 2002

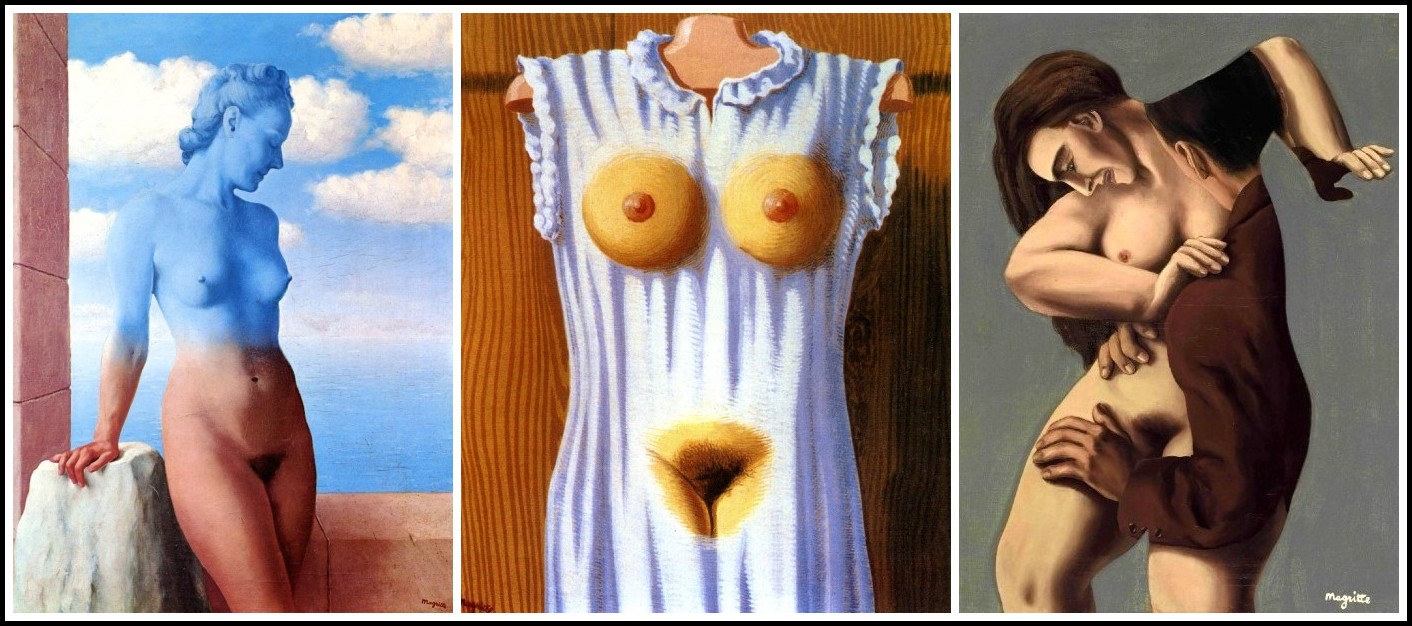

In his depiction of Lulu as a virtual nonentity, devoid of beliefs and opinions, Wedekind takes part in the time-honored tradition that defines the feminine in terms of an absence or lack of the masculine norm. This tradition, which as we have seen finds a foremost exponent in Freud, has received one of its fullest critiques in the writings of the French psychoanalyst Luce Irigaray. A good deal of her work responds either implicitly or explicitly to the neo-Freudian school of which she was originally a member, in particular to those papers of Lacan in which he expounds his theory that woman has been excluded from participation as a subject in the order of language, that she is in effect linguistically castrated. Much of Irigaray’s Speculum of the Other Woman (1974), as well as several of the essays in This Sex Which Is Not One (1977), criticizes the Freudian model that denies subjectivity to woman and instead views her as man’s specularized other or negative reflection.

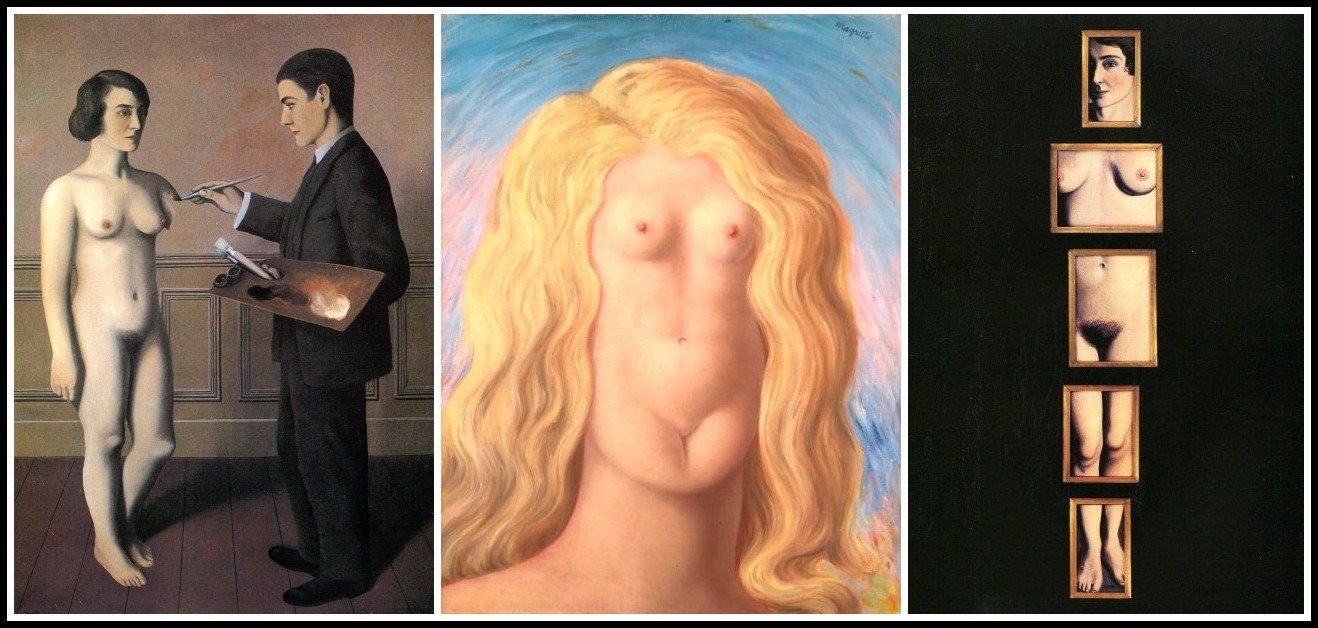

MAGRITTE: Attempting the Impossible, 1928 | The Rape, 1945 | Eternal Evidence, 1930

Irigaray describes the basis of Freud’s model as an economy of representation whose meaning is regulated by paradigms and units of value that are in turn determined by male subjects. Therefore, the feminine must be deciphered as interdict: within the signs or between them, between the realized meanings, between the lines and as a function of the (re)productive necessities of an intentionally phallic currency, which, for lack of the collaboration of a (potentially female) other, can immediately be assumed to need its other, a sort of inverted or negative alter ego—’black’ too, like a photographic negative. Irigaray goes on to elaborate on woman’s function in sustaining the male ego: ‘Now, if this ego is to be valuable, some ‘mirror’ is needed to reassure it and re-insure it of its value. Woman will be the foundation for this specular duplication, giving man back ‘his’ image and repeating it as the ‘same’.’

Guy le Baube, Cupidon, 2013 | Gilles Lambert Godecharle, Cupidon, 1804

Lulu serves precisely this kind of mirroring function for her male admirers: as a veritable tabula rasa, she is perfectly suited to reflect back to them their particular perceptions of and projections onto her. Her function as mirror is underlined by the series of names they give her: ignorant of her ‘primal name,’ Lulu, Schön romanticizes her origins by calling her Mignon, the name of the mysterious girl in Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister whose elderly companion, the harper, is considerably more appealing than Schigolch; the first man to whom Schön marries Lulu off, the wealthy but senile Dr. Goll, calls her Nelli, perhaps a patronizing recollection of Dickens’s Little Nell; the painter Schwarz, to whom Lulu is, in her own words, ‘his wife, his wife, and nothing but his wife’, renames her Eve. Like all the others, her next suitor, the colonial explorer Prince Escerny, projects onto her his own fantasies of what he would like her to be: ‘Yours is a generous nature, unselfish. You cannot bear to see anyone suffer. You are the embodiment of mortal happiness. As a wife you would make a man supremely happy. Your being is all candour, you would make a poor actress’.

GUY LE BAUBE: Dogs, 2002 | Eyelashes, 2005

As Lulu has by this point already brought on Goll’s fatal heart attack (through her flirtations with Schwarz) and then driven Schwarz to suicide (through Schön’s revelation to him of her true background), the dramatic irony of this passage requires little comment. Contrary to Escerny’s image of her, Lulu is in fact a consummate actress, consisting by her own admission of a series of roles; the statement she makes to Schön just before shooting him in self-defense—’I’ve never in the world wanted to be anything but what I’ve been taken for, and no one has ever taken me for anything but what I am’—should be viewed in light of her earlier rhetorical question to his son Alwa: ‘If I hadn’t known more about acting than they do in the theatre I wonder what would have become of me’.

JEANLOUP SIEFF: Corset, 1962 | Carel, 1985

Lulu’s chameleon-like character—a beautiful surface without substance—is highlighted by her love of costumes. The ability to change clothes quickly, which Alwa says she learned as a child, is in Goll’s words her ‘own sphere’. Her first response after a disaster is to change her clothes, as if thereby to rid herself of any unpleasant effects, and her various outfits allow her to slip with ease from one role to another: from middle-class wife to Pierrot to flower girl to cancan dancer to ballerina to Queen of the Night to Ariel to East Indian sailor to jockey. It is surely no accident that the stage directions of both plays devote considerably more attention to descriptions of clothing, in particular Lulu’s clothing, than to details of physiognomy. In her talent as a role-player Lulu is perhaps intended—in anticipation of Mann’s Felix Krull—to represent a type of the artist, her theatrical skills constituting a creative power otherwise denied to the sterile femme fatale. In any case, it is clear that she is to be seen not as the incorporation of a natural principle, as has so often been claimed, but as the embodiment of artifice, carefully oiling, powdering, and dressing herself in an almost dandified manner (in an early version of the play she is even suspected of dyeing and artificially curling the hair in her armpits).

Adolf Steinhäuser, Cupid, n.d. | Guy le Baube, Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat, 1987

The extent to which she has learned the social graces is grotesquely caricatured at the end of Earth-Spirit in the non sequiturs with which she interrupts Schön’s jealous raging as he is on the verge of shooting her: ‘How do you like my new dress?’ and ‘Please order the carriage. We’ll drive to the opera’. The irony, of course, is that he has helped create this ‘whore,’ as he calls her here, having shaped her into a creature to be desired by other men in order to free himself to marry someone more appropriate to his respectable middle-class status. The effectiveness of his training is evident on numerous occasions, as when Alwa and Escerny spend an entire scene discussing which ballerina costume suits Lulu better, the pink or the white.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Laura Aikin (Lulu) & Alfred Muff (Schön) | Zurich Opera House, Franz Welser-Möst, 2002

Lulu’s exhibitionist fascination with dress and style is crucial to her feminine function as an image of visual perfection, inviting the male gaze. Because her role as beautiful spectacle is so pronounced, it can be usefully illuminated by recent work on narrative cinema, the genre in which, as Teresa de Lauretis writes, ‘the representation of woman as spectacle—body to be looked at, place of sexuality, and object of desire—so pervasive in our culture, finds its most complex expression and widest circulation.’ In her highly influential article ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,’ Laura Mulvey uses psychoanalysis to explore the ways in which the fascination of film is reinforced by social patterns that have molded directors and viewers alike. Because of the sexual imbalance characteristic of these patterns, she writes, the pleasure in looking afforded by cinema has conventionally been split between the male as active bearer of the look and the female as passive receptor of it: The determining male gaze projects its fantasy on to the female figure, which is styled accordingly. In their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously look at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness. Woman displayed as sexual object is the leitmotif of erotic spectacle: from pinups to strip-tease, from Ziegfeld to Busby Berkeley, she holds the look, plays to and signifies male desire. Mainstream film neatly combined spectacle and narrative.

JEANLOUP SIEFF: Nu sur un lit, 1976 | Téléphone Paris, 1981

Thus narrative cinema exploits in paradigmatic fashion the dichotomy between man as spectator and woman as spectacle which has informed the history of painting. As Mulvey goes on to observe, however, in psychoanalytic terms the female figure also connotes to the male viewer the lack of a penis, implying a threat of castration and hence unpleasure. For the male unconscious there are two solutions to this problem: either to show that the woman’s castration is the result of guilty conduct or to disavow her castrated state by turning her into a fetish—in other words, either devaluation or overvaluation. The first alternative produces the female criminal as cinematic character, the second the female star. Both strategies for neutralizing the male viewer’s anxiety can be found in the same film, as Kaja Silverman demonstrates with reference to Ophüls’s Lola Montès (1955); documenting the rise and descent of an actual nineteenth-century courtesan, the movie both establishes Lola as fallen woman and circles around her as spectacle.

Marlene Dietrich, Portrait for Shanghai Express, 1932 | Greta Garbo, Portrait for Anna Karenina, 1935

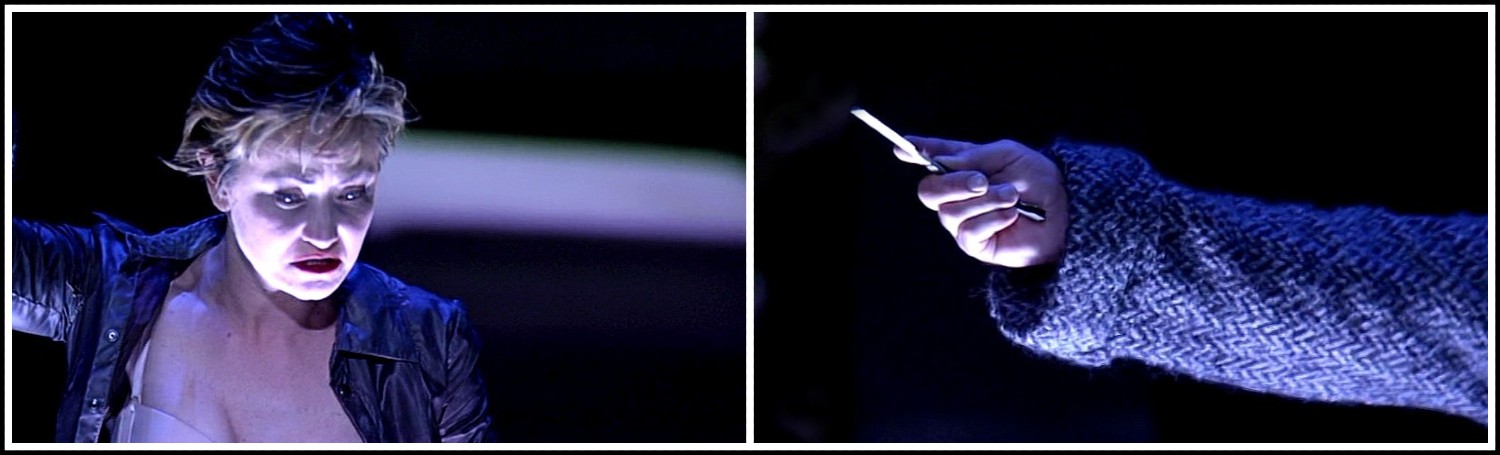

It is not insignificant that both Lola Montès and Lulu are first glimpsed on display, immobile, in a circus. For like Ophüls’s film, Wedekind’s Lulu plays combine the strategies of overvaluation and devaluation of the female in portraying the rise and fall of a femme fatale, and Lulu’s rise, like Lola’s, is marked by her function as fetishized spectacle. This function is most apparent in three scenes in Earth-Spirit which might be called embedded spectacles (within the overall spectacle of the drama itself): the prologue in front of the circus tent, Lulu’s appearance first in and then posing for her portrait, and her performance as a dancer. All three of these scenes, focusing on her as a sensually alluring figure, are analogous to those scenes in narrative cinema which, in Mulvey’s words, ‘freeze the flow of action in moments of erotic contemplation of a beautiful female star’.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Laura Aikin (Lulu) | Zurich Opera House, Franz Welser-Möst, 2002

It is difficult to imagine more of a spectacle atmosphere than the circus setting in which the prologue to Earth-Spirit takes place. As instructed by the animal tamer, who first previews Lulu as ‘the wild and lovely animal, the true’, a worker carries her in and sets her down in front of the big top, where she sits silently while the animal tamer fondles her and tells her how to behave. His significance is clear from an observation made by Louise Brooks, whose portrayal of Lulu in Pabst’s 1928 silent film Pandora’s Box brought her overnight fame. In her autobiography Brooks comments, ‘The finest job of casting that G. W. Pabst ever did was casting himself as the director, the Animal Tamer, of his film adaptation of Wedekind’s ‘tragedy of monsters’.’ Both Lulu’s treatment as an animal and the costume she wears—that of a Pierrot, a stock character of cormmedia dell’arte (as Pedrolino) and old French pantomime—emphasize her silence. Hardly any other work of literature provides better evidence than Earth-Spirit for what Mary Jacobus says might be ‘the hidden message which a feminist critique uncovers’: ‘Shut up already’.’

Alban Berg, Lulu, Andreas Hörl (Animal Tamer) & Patricia Petitbon (Lulu) | Orchestre Symphonique du Gran Teatre del Liceu, Michel Boder, 2010

Our next glimpse of Lulu is not of the living character but of her portrait as Pierrot, which Goll has commissioned Schwarz to paint. Gazing at this spectacle alongside the picture of his fiancée on which Schwarz is also working, Schön gives us an early indication of Lulu’s role as attractive surface without core, commenting that she is ‘a diabolic beauty,’ whereas his fiancée’s portrait shows ‘more substance’. But perhaps the most striking instance in the entire drama of Lulu’s role as silent spectacle occurs in the next scene, in which she stands on a raised platform posing for Schwarz in her Pierrot costume while Goll and Schön sit watching. Since this is the only one of the three embedded spectacles in the play which allows us to observe Lulu’s spectators observing her, the voyeuristic pleasure that underlies the fascination of drama is particularly great here, insofar as the theatergoer identifies with Goll and Schön in a kind of doubling effect.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Will Hartmann (Schwarz) & Patricia Petitbon (Lulu) | Orchestre Symphonique du Gran Teatre del Liceu, Michel Boder, 2010

An illuminating analogy is again provided by narrative cinema, much of whose appeal is also based on voyeurism: the visual dynamics of this scene in Earth-Spirit are similar to those of Alfred Hitchcock’s film Marnie (1964). Raymond Bellour, noting that in American English ‘one says, when describing a woman: ‘her looks’; as though her ‘looks’ were nothing but that image constituted through the looks given her by men,’ points out that Hitchcock has inserted himself into the chain of male looks that constitute Marnie: after a segment in which Marnie’s employer and a client of his elaborate on her ‘looks’ to the police following her theft and disappearance, Hitchcock himself appears in the hall of the hotel where she has gone, first watching her walk down the hall and then turning toward the spectator, ‘staring at the camera which he is, whose inscription he duplicates. The spectator in turn (re)duplicates this inscription through his identification with both Hitchcock and the camera’.

Alfred Hitchcock, Marnie, 1964

The ‘looks’ given to Lulu in this scene of Wedekind’s play render her art-like: Schön tells her she is a ‘picture before which Art must despair’ and instructs Schwarz to ‘treat her as a still-life’. Schön’s fantasy is clear: if this woman he helped create would only behave like a work of art—silent, framed, and immobile—all his troubles would be over.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Patricia Petitbon (Lulu) & Will Hartmann (Schwarz) | Orchestre Symphonique du Gran Teatre del Liceu, Michel Boder, 2010

If this fantasy is not realized, the actual work of art Schwarz produces—the painting of Lulu in her Pierrot costume—does remain. Displaying her at the peak of her beauty, the painting continues throughout both plays to be crucial to her identity as a desirable female, to what might be called her ego ideal. For her status as an attractive woman, as a pretty package, is more than merely pleasurable for Lulu; she regards it as her salvation. This is especially evident at the end of Earth-Spirit, where she attempts to use her appearance to persuade Alwa not to turn her over to the police for murdering his father: ‘Don’t let me fall into the hands of the law. It would be such a pity! I’m still so young. I’ll be true to you all my life. Look at me, Alwa, look at me, man! Look at me!’ (emphasis mine). Lulu’s need to see her portrait as soon as she gets out of prison is evidence of the same phenomenon, as is the fact that, when she is later so down-and-out that her looks have faded, she cannot bear to see the beautiful portrait with which she can no longer identify.

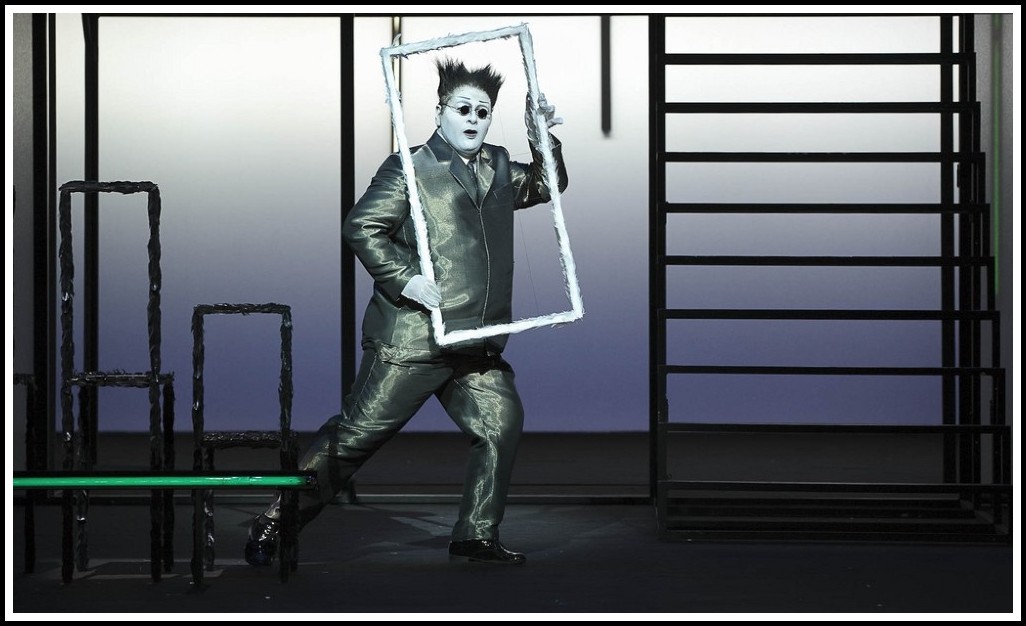

Frank Wedekind, Lulu, Robert Wilson | Photo: Lesley Leslie-Spinks

Lulu’s reliance on her portrait as mirror reflection is bound up with her narcissism, a condition not incongruous with her education into beautiful surface without substance. Like Schnitzler’s actress, she is constantly parading her awareness of her attractiveness, claiming to Goll while posing for Schwarz that she looks ‘equally well from all sides’ and to Alwa that when she saw herself in the mirror in her Parisian evening gown, she ‘wished [she] were a man, [her] own husband’. Escerny observes that ‘when she dances her solo she is intoxicated with her own beauty—seems to be idolatrously in love with it’. And, as Freud was to do a few years later, Wedekind presents the narcissistic woman as all the more fascinating for her self-contentment. Again and again Lulu is placed before mirroring surfaces. The mirrors in her dressing room give way to a gleaming dustpan when she is in prison, and in the opinion of the white-slave dealer Casti-Piani, the picture of her as Eve before the looking-glass is her grandest. Her self-involvement is epitomized in the early scene where she is left alone with Schwarz; when he commands her to look him in the eyes, she responds, ‘I can see myself as a Pierrot in them’. The melancholy introspection conventionally associated with the Pierrot figure in nineteenth-century literature and painting is replaced here by narcissistic self-absorption. But Lulu’s narcissism is essential to her sociocultural construction as a paradigmatic female. In the words of Judith Kegan Gardiner, ‘In film, as in literature and life, women are accustomed to seeing themselves being seen, to valuing themselves according to others’ evaluations of their appearance.’

Frank Wedekind, Lulu, Robert Wilson | Photo: Lesley Leslie-Spinks

As the one largely responsible for Lulu’s identity as spectacle, Schön has affinities with a number of artist figures. Enamored of his creation, he is both a Pygmalion and a Henry Higgins, having rescued Lulu from her existence as an indigent flower girl. Unable to separate himself from his work of art, with whom he says he has so grown together that, were he to divorce her, half of himself would go with her, he is also a René Cardillac, E. T. A. Hoffmann’s prototype of the romantic artist in ‘Das Fraulein von Scuderi,’ who is irresistibly compelled to repossess the jewelry he fashions. And he is of course a Frankenstein as well, ultimately destroyed by the monster he has created. Lulu is anything but art for art’s sake, however. She has for Schön, as for her first foster father, Schigolch, concrete monetary value, and she is exchanged accordingly: having passed her to Schwarz after Goll’s death, Schön seeks to comfort Schwarz in his despair at learning of her infidelities with his repeated exclamation ‘You married half a million!’. Following Schwarz’s suicide Schön puts her up for sale again, making her into a dancer ‘so that someone should come and take me away,’ as she puts it. In this third embedded spectacle in the play Schön is intent on keeping his beautiful product well exposed, telling her to remain more downstage, urging Alwa to make her costumes more revealing, and forcing her to dance even though she does not want to appear before his fiancée.

Frank Wedekind, Lulu, Robert Wilson | Photo: Lesley Leslie-Spinks

In his extensive discussion of the commodity in the first part of Capital, Marx describes the commodity—guardian relationship in the following statement and footnote: Commodities cannot themselves go to market and perform exchanges in their own right. We must, therefore, have recourse to their guardians, who are the possessors of commodities. Commodities are things, and therefore lack the power to resist man. If they are unwilling, he can use force; in other words, he can take possession of them. In the twelfth century, so renowned for its piety, very delicate things often appear among these commodities. Thus a French poet of the period enumerates among the commodities to be found in the fair of Lendit, alongside clothing, shoes, leather, implements of cultivation, skins, etc., also femmes folles de leur corps (wanton women).

Frank Wedekind, Lulu, Robert Wilson | Photo: Lesley Leslie-Spinks

The relevance of this description to Lulu and her father figures is obvious. Lulu’s function as commodity can be seen to fit into a larger framework defined by Irigaray. Echoing Claude Lévi-Strauss, Irigaray goes so far as to claim that Western culture is based on the exchange of women. Taking Marx’s analysis of commodities as her point of departure, she writes that women, like commodities, are used and passed from one man or group of men to another; like commodities women are products of men’s labor and hence serve as signs of male power.

Frank Wedekind, Lulu, Robert Wilson | Photo: Lesley Leslie-Spinks

The commodity—guardian parallel holds true for Lulu’s relationships not only with her father figures but with other men as well. Moreover, the consumer society within which she functions as a commodity, first as a child with Schigolch and then as an adult, leaves its mark on the language of both plays. Married to Schwarz, Lulu complains that he is ‘wasting’ her, and Alwa later uses the same word in warning her as a dancer not to ‘waste’ her strength before her final appearance. More graphically, lamenting the literary trends that have led to a decline in the popularity of the circus, the animal tamer tells his audience at the beginning of the prologue to Earth-Spirit, ‘My pensioners are short of fodder / So at the moment they devour each other’; within the same realm of imagery, Alwa compares the atmosphere in the theater where Lulu is dancing to the frenzy of a menagerie at feeding time. The degree to which Lulu has internalized her role as object of consumption is evident in the reason she gives Schigolch for oiling and powdering herself so carefully each day: ‘I want to be good enough to eat’. The process of consumption is not one-sided, however, as Casti-Piani’s comment about Lulu’s ‘heavy consumption’ of men makes clear.

Frank Wedekind, Lulu, Robert Wilson | Photo: Lesley Leslie-Spinks

The commodification of Lulu is most apparent in Pandora’s Box. Whereas her function as fetishized spectacle predominates during her rise as a femme fatale, her role as commodity prevails during her fall, which begins with her murder of Schön at the end of Earth-Spirit. In the terms that Mulvey sets out and Silverman takes up in discussing the fortunes of Lola Montès, it is at this point that overvaluation gives way to devaluation, that star becomes criminal. Pandora’s Box presents us with one male character after another trying to ‘cash in on’ Lulu: the variety acrobat Rodrigo, guided by his conviction that ‘it’s not half as much of an effort for a woman to support her husband as the other way about’, plans to train her as a trapeze artist after their marriage and then live on her income; Casti-Piani intends to make a large sum by selling her into prostitution in Egypt; and after her escape from prison both threaten to turn her back over to the police if she refuses to comply with their wishes. Even Alwa has profited from her, by taking her life as the subject of his play. In the tradition of her mythological ancestor Pan-dora, Lulu not only is ‘all-gifted’ but becomes a ‘gift for all’.

Frank Wedekind, Lulu, Robert Wilson | Photo: Lesley Leslie-Spinks

Schigolch’s sending Lulu down into actual street prostitution in London in the final act of Pandora’s Box, thereby completing the circle he had begun in her childhood, is thus simply the most literal manifestation of a process that has been going on throughout both dramas. Appropriately, her customers can be read as grotesque versions of her husbands and suitors: the deaf-mute Hunidei, who keeps putting his hand over her mouth, parallels Goll, who commissioned Schwarz to ‘silence’ Lulu into a portrait; the brutal African prince Kungu Poti is reminiscent of Prince Escerny, who is in his own words ‘forced to exercise a quite inhuman despotism’ on his voyages of exploration; the Swiss professor Hilti, who responds to Lulu’s question about whether his fiancée is pretty by answering ‘Yes, she has two million’, echoes Schön, who equates Lulu with half a million; and Jack the Ripper, after murdering Lulu, utters the same phrase that Schön had used after enlightening Schwarz about her true character (and thus occasioning his suicide): ‘That was a good piece of work!’. But the crassest example of Lulu’s commodification was eliminated from the final edition of the play. In the early manuscript version, Jack, the quintessential embodiment of male sexuality perverted, tucks a newspaper package into his breast pocket after murdering…

Alban Berg, Lulu, Laura Aikin (Lulu) | Zurich Opera House, Franz Welser-Möst, 2002

…and dissecting Lulu and speculates about how much money the London Medical Club will pay for this ‘prodigy’—the part of Lulu denoted, in vulgar parlance, by the ‘box’ of the play’s title.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Rolf Haunstein (Jack the Ripper) | Zurich Opera House, Franz Welser-Möst, 2002

But what about Wedekind’s attitude toward Lulu’s grisly fate? Are we to view it as a wish-fulfillment fantasy of male revenge for the snares of female sexuality or as a condemnation of woman’s utmost victimization? The drama has been read both ways, and indeed, the Lulu plays offer one of the most profound examples in turn-of-the-century literature of the ambiguity characteristic of male portrayals of women. On the one hand the character Lulu is, as we have seen, clearly a product of her socialization; her roles as spectacle and commodity grow out of a patriarchal capitalist system in which men control both women and money. The implication of this view—that women are not inherently inferior or evil and that the only way to improve their lot is to abolish capitalism—places Wedekind on the side of socialist thinkers such as Engels and Bebel, who supported the feminist struggle for equal rights while doubting its effectiveness as long as the current economic structure remained intact. Certainly Wedekind’s drama Der Marquis von Keith (1900), a harsh portrayal of the emotional and spiritual bankruptcy of human beings in a capitalist society, would support this kind of categorization.

Frank Wedekind, Lulu, Robert Wilson | Photo: Lesley Leslie-Spinks

On the other hand, to identify Wedekind with the feminist cause is misleading, since in the Lulu plays as well as in other works he seems to take pleasure in making fun of the turn-of-the-century women’s movement. At the end of Pandora’s Box Geschwitz, following her ludicrous failed attempt to hang herself in despair at Lulu’s indifference to her, resolves to return to Germany to study law and fight for women’s rights. Similarly, in the prelude to Die junge Welt, mentioned earlier in the context of Wedekind’s concern with education, several girls form a women’s rights group and vow not to marry until the sexual inequalities characterizing the education of women have been completely removed, yet in the course of the play one after the other forgets her pledge and enters a traditional marriage.

Herman Landschoff, Junior Bazaar, 1946

And in Death and Devil (1905) Casti-Piani reappears to convince a prudish member of the International Society for the Suppression of White Slave Traffic that the ability to sell their bodies is women’s only advantage over men and that sensual pleasure is the one joy in a world deadened by the hypocrisy of bourgeois society. But his belief that prostitution is the result of female sexual desire is unmasked as an illusion through the confession of one of the girls in his bordello, who reveals that her work there has failed to satisfy her raging masochistic lust. Her stance echoes Lulu’s description to Alwa of her recurrent (and prophetic) dream of being attacked by a sex murderer, which she immediately follows with a request for a kiss. Wedekind’s attribution of masochism to women, paralleling Freud’s views, as well as other evidence of his belief in the existence of polar differences between the sexes, places him on the side of notorious ‘hysterizers’ such as Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, and even Weininger.

RENE MAGRITTE: La magie noire, 1935 | Philosophie dans le boudoir, 1966 | Les jours gigantesques, 1928

Evidently Wedekind is not to be pinned down. In their open-endedness the Lulu plays encourage critics, directors, and even audiences to project their own preconceived notions of femininity onto Lulu, thus imitating the male characters in the dramas themselves. Created by a man to represent ‘woman’—in her ‘primal form’—Lulu is of necessity marked by ambivalence. For ambivalence has typified depictions of the female ever since Hesiod told the story of Pandora, who is remembered for bringing into the world not only evil but also hope.

Botticelli, The Birth of Venus, 1485 (detail) | Giulio Bonasone, Epimetheus opening Pandora’s Box, 1550 | John Collier, Lilith, 1887

GAIL FINNEY: THREE BOOKS

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2024 | All rights reserved

Comments