An In-Depth Analysis

MANET’S CONTEMPLATION AT THE GARE SAINT-LAZARE – PART 1

Harry Rand

Posted by kind permission of Harry Rand, Art Historian, former Senior Curator of Cultural History at the Smithsonian Institution

From Harry Rand, Manet’s Contemplation at the Gare Saint-Lazare (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987 (pp. 3-49)

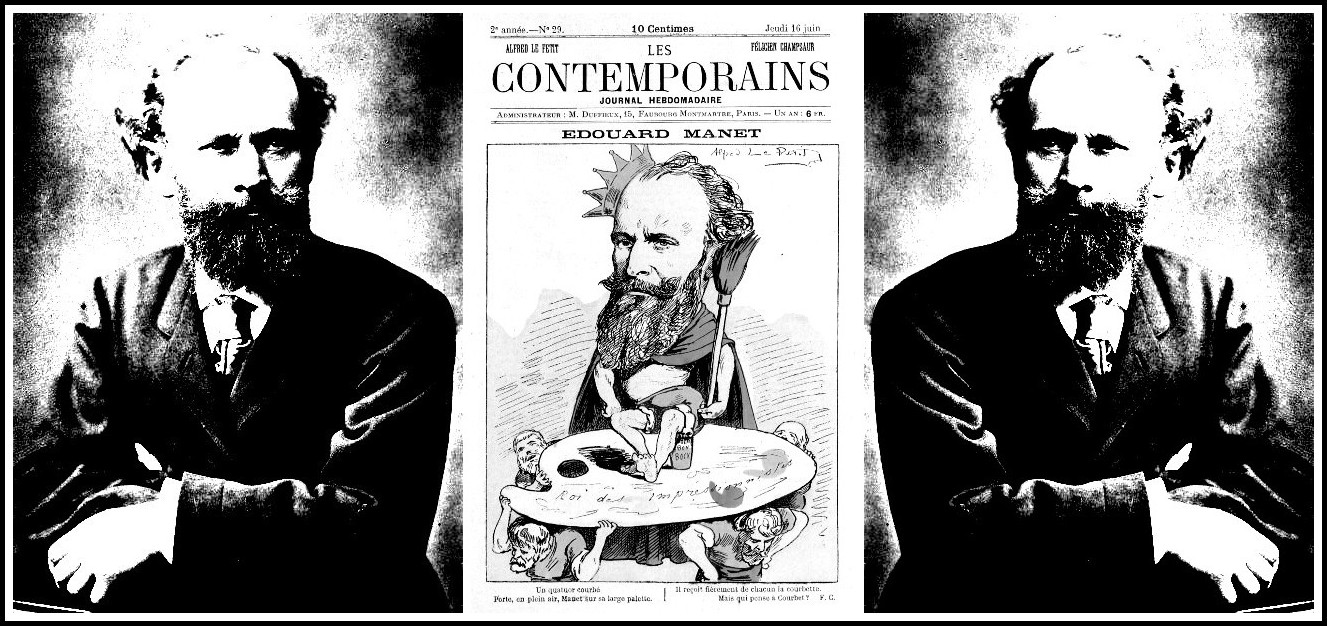

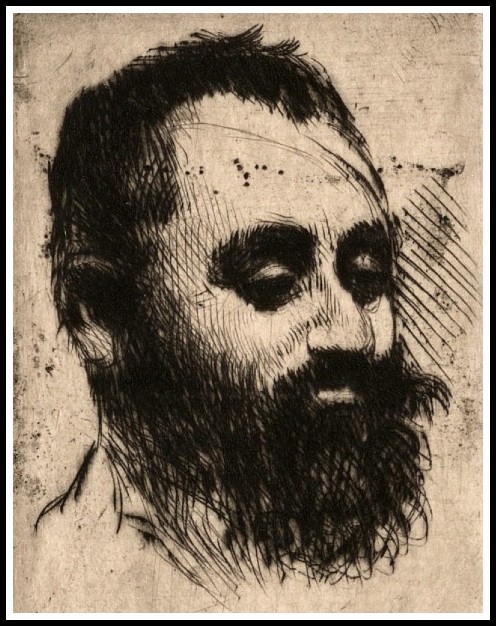

Alphonse Leroy, Edouard Manet, BnF (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

I. INTRODUCTION

Edouard manet apparently quoted such diverse materials that not one of his works has yet been convincingly explicated to general satisfaction, despite prolonged disputation. Luckily, his reputation has not suffered from the disunity of his supporters. Quite the contrary. Two generations after the scorn of his first spectators had died away, a solid critical and art-historical admiration of Manet arose and evolved into two camps. One camp considered Manet to have been a genial genius, a painting ‘animal’ from the upper class; the other camp thought of him as secretly ‘difficult,’ prefiguring the ‘difficulty’ of modern art. In reading the most prominent art historians on Manet, one can almost be convinced that they are writing about several different artists. There is simply no agreement on the propelling force for this artist, who lived the life of a bourgeois, free from basic want (uncharacteristic of striving unappreciated artists in midcareer). Since Manet himself did not greatly enlighten us about his ambitions, the direction he actually charted for his work and the ideals toward which his art was moving are still debated. Even if Manet had provided us with his own explanations, what he deemed important about his painting in the last quarter of the nineteenth century might not at all respond to what we must learn about him today. After a century of earnest inquiry, we still have no consensus about the deepest motives of Manet’s art.

Fernand Desmoulin, Portrait d’Édouard Manet, 1883 | La Vie Moderne / Étienne Carjat, Edouard Manet, BnF

At a certain level Manet reveals himself to be reconcilable to otherwise contradictory descriptions of him, and at that level appear the critical (and heretofore frequently overlooked) assumptions that governed his art. This essay attempts to locate the station of consistency in Manet’s art. Although the approach taken will not be direct, our attention will not waver from a single guiding focus. The focal point will be Manet’s painting, The Gare Saint-Lazare, 1873, which will serve as the instrument by which this reconciling examination is carried out. An intensive discussion of this work will show that it engages most of the critical issues of the period of its execution and of the artist’s work generally.

Manet, The Gare Saint-Lazare, 1873

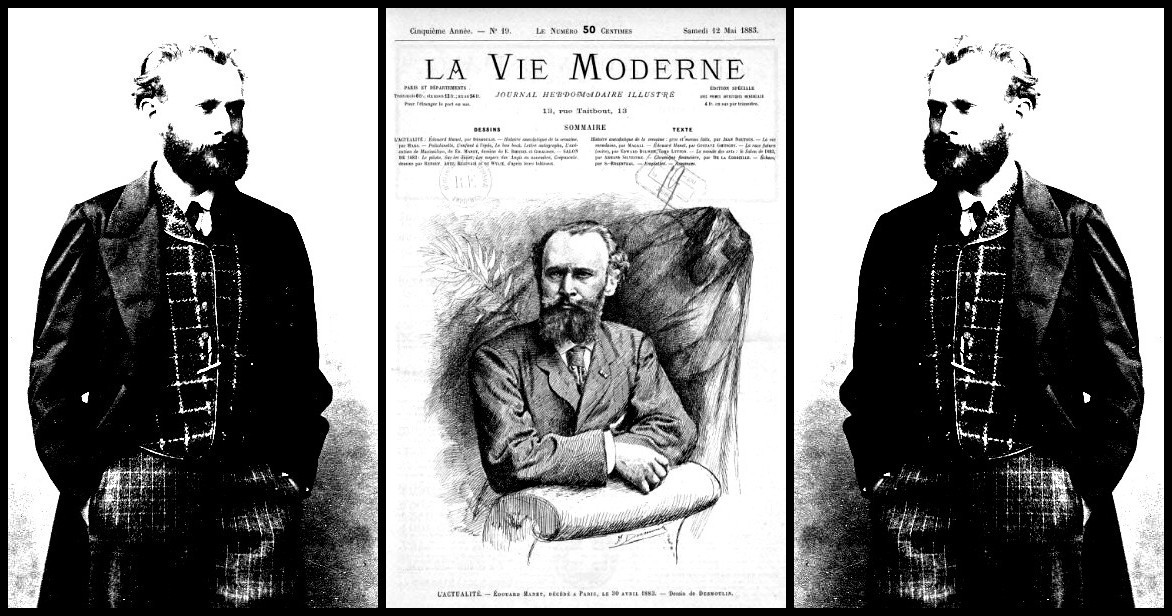

Several interlocking problems snare those spectators who desire overall access to Manet’s art. In his youth Manet produced images of obvious thematic complexity. These works have revealed a network of tantalizing gestures toward art of the past, a past that Manet invoked by adapting motifs from the artists he most admired. A concise summary of Manet’s use of sources was published by Michael Fried and is worth quoting at length: The problem of the meaning of Manet’s use of sources first arose in 1861 when the critic Ernest Chesneau spotted the painter’s adaptation in his Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1862-63) of a figure group from Marcantonio Raimondi’s engraving after Raphael’s Judgement of Paris.

Manet, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, 1863 (detail) | Raimondi after Raphael, The Judgment of Paris, ca. 1510–20 (detail)

That same year, a more distinguished critic, Theophile Thoré, remarked in the course of a largely favorable review that Manet had ‘pastiched’ Velazquez, Goya, and El Greco and called attention to certain striking similarities between Manet’s art and the work of other old masters. Thereafter the topic was largely moot, until 1908 when the German art historian Gustav Pauli rediscovered the Marcantonio connection. But it was not until the 1930s and 1940s that the astonishing range of Manet’s quotations from, allusions to, and adaptations of earlier works of art became apparent to scholars. Confirmed by a phenomenon seemingly without precedent in their experience, they mostly saw in it either a sign of deficiency—thus Manet was criticized for being unable to compose—or a hallmark of modernity—indicating a laudably formalist indifference to subject matter as such. By the 1950s and 1960s, it was often said or implied that Manet intended his use of sources at once to identify with and to compete with the old masters, though it was never explained why he should have felt a special need to do so or, indeed, why he should have chosen to identify with and compete with them in this particular way.

Manet, Le Balcon, 1869 (detail) | Goya, Las majas en el balcón, 1810 (detail)

Once discerned amid his early pieces, these references graph the artist’s private art history—that inner vision of art’s development upon which every artist bases his endeavor and which is, ultimately, a personal conviction (as is also the case for every art historian). In the early 1870s, Manet rather abruptly stopped making these intense composite pictures and turned to making sunnier and apparently simpler images. The first task of this essay will be to demonstrate that after 1870, Manet wove the materials furnished by modernity into the same complex patterns as those that united his historical sources. The patterns of thought typical of his early works were maintained throughout his life. This will be a difficult point to demonstrate, for nothing in The Gare Saint-Lazare’s subject seems remarkable, and viewers have not been especially struck by what is depicted: Encouraged by having at last had a success at the Salon, by the fact that Durand-Ruel had recently bought a number of his paintings and, not least, by the gaiety which had returned to Paris with the Third Republic, Manet resumed painting scenes which would express some of the more agreeable aspects of the life of his time. Outstanding among these are Le Chemin de Fer.1 According to this prevalent view, Manet was a painter of bourgeois life, of superficial human concerns. Whatever sensibilities he possessed as a painter remained unlinked to an intellectual framework worthy of that manual skill. Unlike those tragic artists whose biographies compel our attention and whose living conditions seem to have molded their art, Manet’s extra-artistic activities hardly inform his work. Occasionally, sharp political news or fierce topical events provoked the attentions of his art, but he does not appear to have taken actions that would have jeopardized his artistic or social standing. He has been described as, ‘respectable to the point of affectation.’2

1 – John Richardson, Manet (London: Phaidon, 1967) p.27

2 – Nicholas Wadley, Manet (London: Paul Hamlyn, 1967) p. 7

Nadar, Manet, BnF | Félicien Champsaur, Caricature d’Edouard Manet, 1881 (BnF)

Other descriptions of this aspect of Manet’s character are neither so concise nor so kind: A gentleman painter, a man about town, Manet only skimmed the surface of some of the more vital things in life. The portraits and photographs we have of him fail to excite our interest. The things he had to say—as recorded by Antonin Proust and by Baudelaire in La Corde—amount to little more than small talk, lit up now and then by a flash of wit or plain common sense.1 According to such reconstructions of his personality, Manet was singularly undisposed to serious or difficult thought. Such an unlikely figure appears to have been a doubtful candidate for changing the quality or the course of late-nineteenth-century subject matter.

1 – Georges Bataille, Manet: Biographical and Critical Study (Geneva: Skira: 1955) p. 18. Here we see Manet portrayed as a kind of idiot savant who passes through life painting but without registering much of the world.

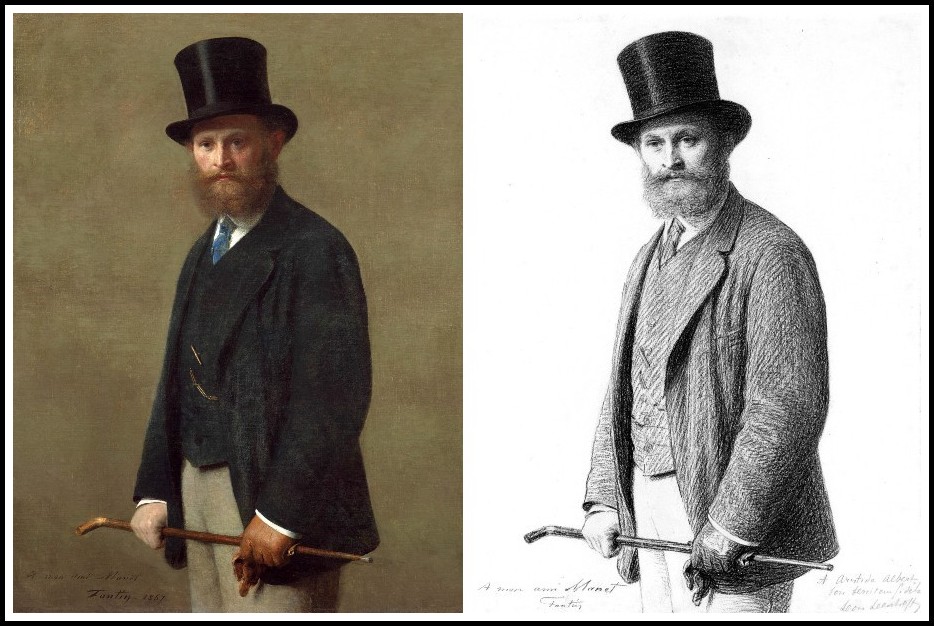

Henri Fantin-Latour, Édouard Manet, 1867 & 1880

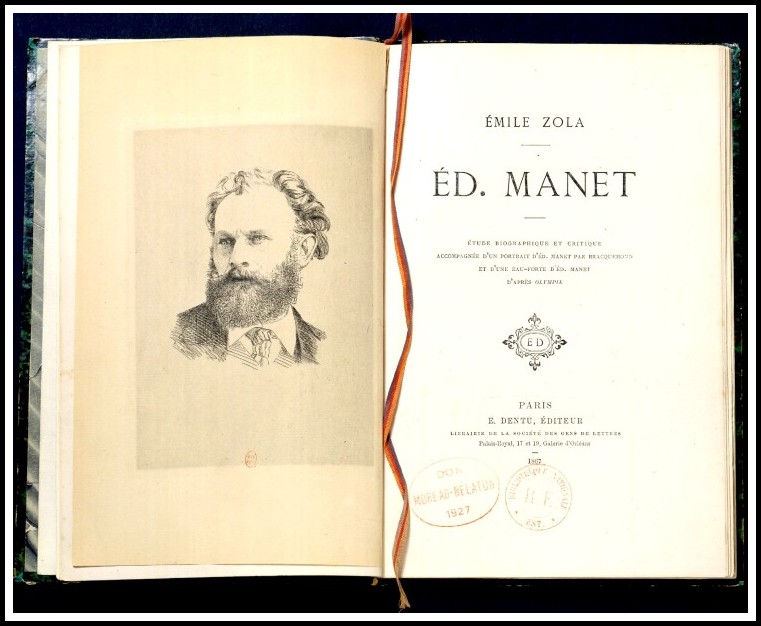

Moreover, should this improbable character have ventured into the world of serious thematic speculation, he would seem foredoomed to failure. Unfortunately, this vision of Manet’s personality cannot be dismissed out of hand, as some aspects of his art suggest that Manet never did master complex subjects. The idea that Manet was a great natural painter with few, if any, ideas derives from Zola’s point of view expressed in his booklet Edouard Manet, published in Paris in 1867.1 Manet’s detractors in this regard were not always academicians or conservative pedagogues. This vision of the artist persisted in some circles until very recent times. The durability of this opinion can be attested by Beatrice Farwell’s recollection that in 1945 I heard Fernand Léger maintain that ‘Manet was the greatest tragedy of the nineteenth century: a gifted painter who had nothing to say’. If Manet truly had nothing to say, that would indeed be a great tragedy. But if his statements were random—thoughtless, pointless in the aggregate, or so far beneath the level of his talents as a painter that discovering his meaning would serve only to diminish his stature—that would be an even greater tragedy. Unfortunately, Manet left no key to the images that appear in his works, and there is as yet no concordance by which we might ascertain whether a fundamental personal program threaded his career.

1 – George Mauner, Manet: Peintre-Philosophe, p. 1 n. 2. Zola’s supportive article of 1866 was expanded and appeared in the Revue du XIXe siècle on 1 January 1867. In 1879, however, a Zola article published in a Russian journal and reprinted in France was highly critical of Manet and the Impressionists.

Emile Zola, Edouard Manet, étude biographique et critique | Bracquemond, Edouard Manet, 1867 | BnF

Our expectations of gaining his privacy have been falsely elevated by our acquaintance with over-documented lives. The questions we pose about his career are, in many cases, answerable for his contemporaries. Neither a markedly eloquent nor a particularly prolific correspondent, Manet eludes us. We yearn to approach his flickering personality over the distance of more than a century, and our curiosity is not slaked by the little we know of him. Manet looms over his times as an intensely private man whose personal code of behavior thwarts the historian in his pursuit. If Manet’s private thoughts were not recorded to our satisfaction, neither was he especially forthcoming about what his subjects may have ‘meant’ or ‘stood for’ in his mind. We learn very little about this when guided by the artist’s writings and from the recollections of his contemporaries. What he mainly painted, ‘modern life,’ such as we see in The Gare Saint-Lazare, was so usual, so seemingly banal and obviously the texture of the world as it was available to countless nineteenth-century Europeans, as to be virtually invisible as subject matter in any special or allegorical sense. At first glance, The Gare Saint-Lazare might seem to be an unpromising spot in which to prospect for an entrance to his thinking. Indeed, even the most careful study of this painting fails to reveal anything of diaristic note. As Françoise Cachin declared, Edouard Manet remains one of the most enigmatic, least classifiable artists in the history of painting.

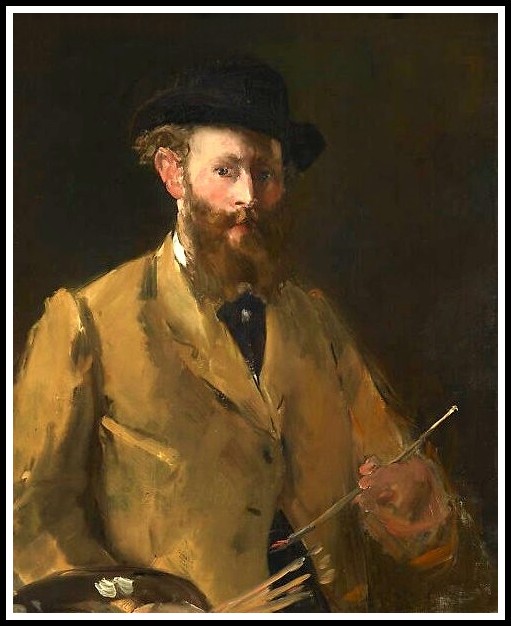

Manet, Portrait of the Artist (Manet with Palette), 1879

Historians wishing to impute special meaning to Manet’s works require that his subjects be assigned some extraordinary potency. Art history was aided in this quest by circumstance, as Manet’s sources describe a network of references that gloss the art of the past. We thus confront two Manets. One was a rather frivolous type, a genial member of the upper class who, regardless of his innate painting skills, seemed unable to substantially advance the plastic imagery of his time or to prefigure the future. The other is a fleetingly glimpsed figure of subtle mind and limber wit whose furthest thematic explorations have hardly been charted.

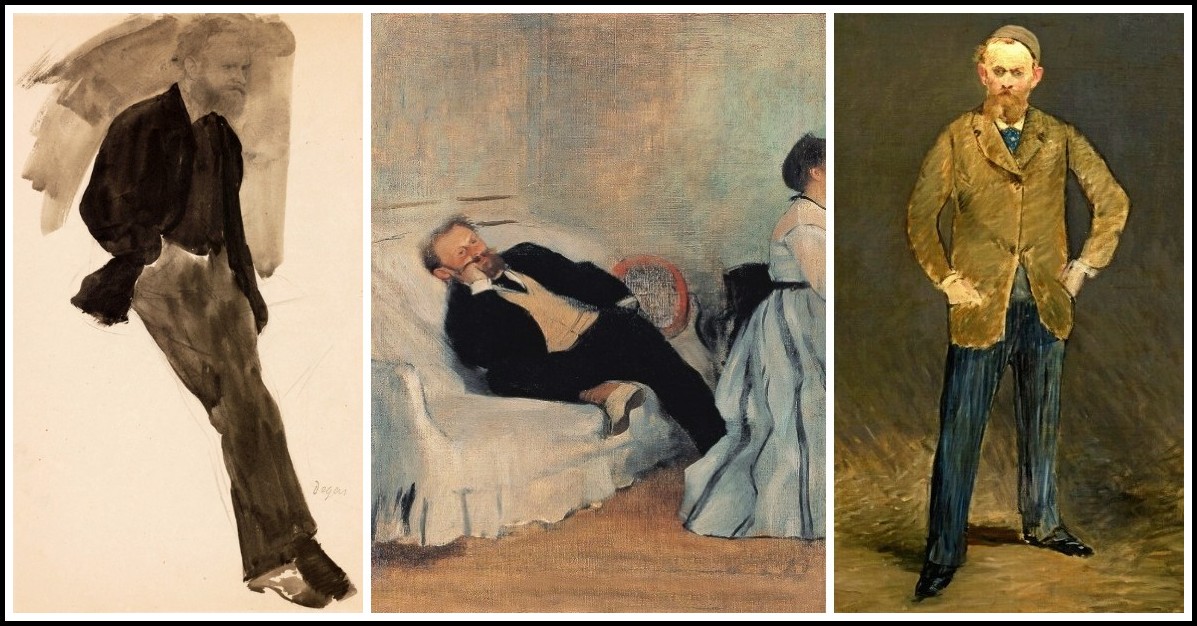

Degas, Edouard Manet Standing, 1868 | Degas, M. et Mme Edouard Manet, 1869 (detail) | Manet, Self-Portrait, 1879

Some have argued that Manet’s subject matter contributed only modestly to his art, except arcanely, as a subterranean criticism of Western culture itself—a convenient reading of him as an ancestor, or progenitor, of modernism. The treatment of Manet as the fountainhead of modernism precludes (and almost proscribes) the presentation of certain kinds of evidence to demonstrate the character of his thinking. According to this view, Manet’s stylistic proclivities were employed to depict his pedigree for modern art—Velázquez, Rubens, Raphael, Le Nain, and others. Adaptations from the work of these artists served as homage in a subliminal network of references by which Manet selectively invoked and deferred to a special view of history. According to this reading of The Gare Saint-Lazare, Manet’s formal genius, yoked to a wonderful painterly craft, simply chose a delightful location in which to expand his talents as a painter.

Manet, La Brioche, 1870 | Chardin, La Brioche, 1763

Yet, Meyer Schapiro warned us to look closely at the situations of Manet’s art: Manet has chosen only themes congenial to him—not simply because they were at hand or because they furnished a particular coloring or light, but rather because they were his world in an overt or symbolic sense and related intimately to his personal outlook. Despite Schapiro’s alert to scholars, little has been written concerning the bivalence of Manet’s art. On one hand Manet recorded the commonplaces of life in the nineteenth century and shared with Zola and other naturalists the foundation for his art in the passage of everyday life before the eyes of the viewer. On the other hand, in addition to clearly rendered observations of the flow of unexceptional events around him, Manet treated those almost nondiscursive refinements toward which the first Symbolists strove. In other words, despite its appearance of being firmly grounded in and composed of the appurtenances of reality, Manet’s art strives to penetrate to a world of thought that is perfectly immaterial, replete with emotions and ideas.

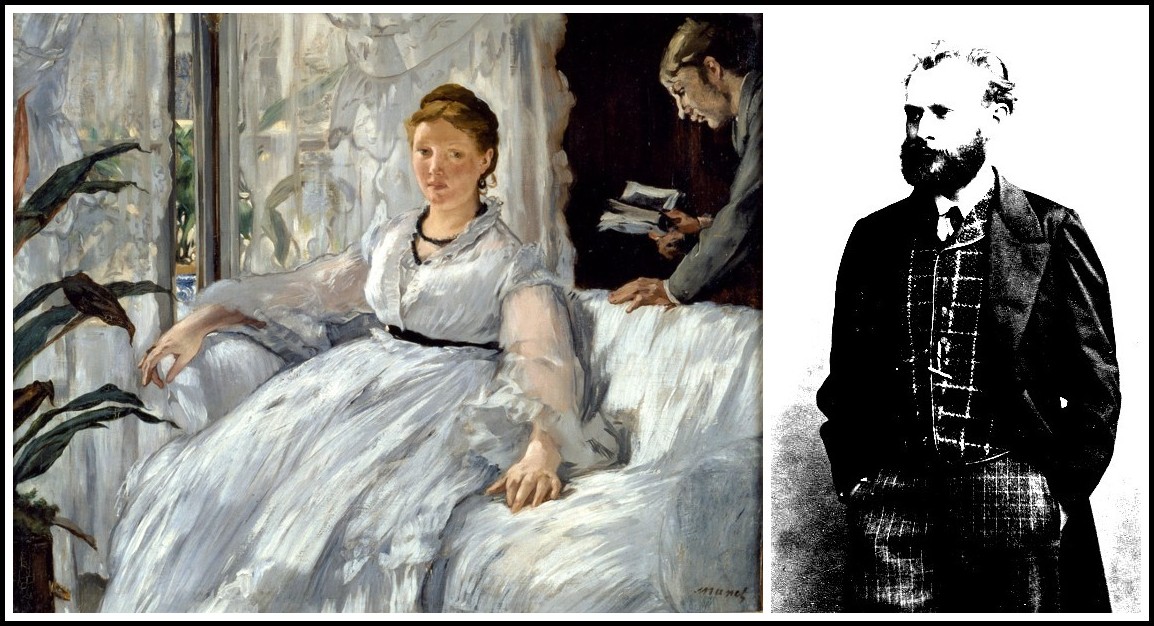

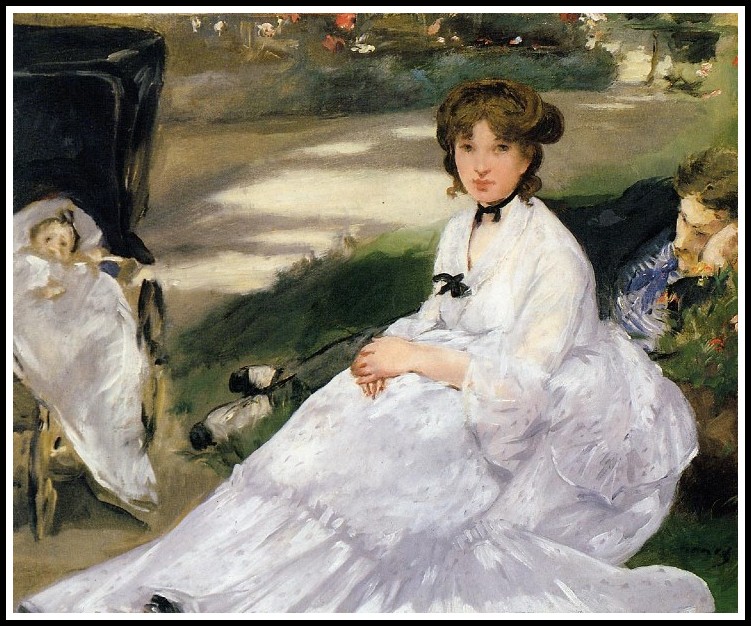

Manet, La Lecture, 1866/1873 | Étienne Carjat, Edouard Manet, BnF

II. FIRST NOTICES

He heard the devastating, the incredible news that the Salon Hanging Committee had accepted only one of the three canvases he had sent in: Le Chemin de Fer. Both Les Hirondelles…

Manet, Les Hirondelles, 1873

…and Le Bal masqué had been rejected.

Manet, Le Bal masqué à l’opéra, 1873

Manet had clearly not kept to the straight and narrow path which Le Bon Bock had seemed to promise. Indeed, the Hanging Committee had accepted one of his works only as an example by which the public could judge how far he had gone astray.1

1 – Henri Perruchot, Manet, tr. Humphrey Hare (NY: World Publishing, 1962) p. 201

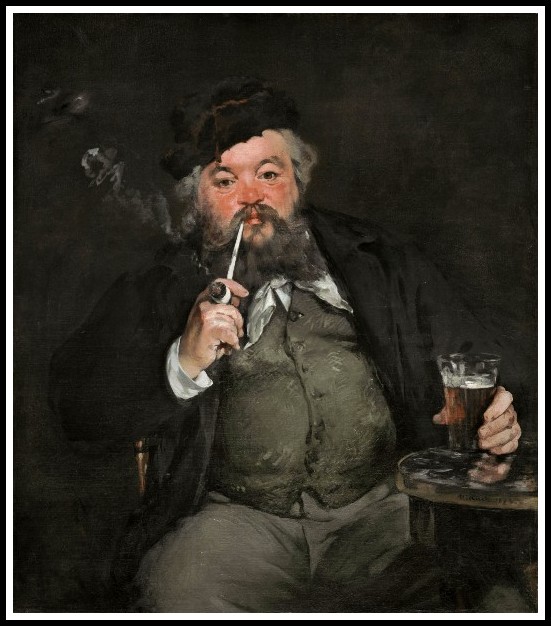

Manet, Le Bon Bock, 1873

To date, the literature that has considered The Gare Saint-Lazare has overlooked the importance Manet himself attached to this painting as well as the place it occupied in his production. In this painting Manet successfully dilated the borders of the canvas to control large surface shapes, and he simultaneously worked unabashedly in the Impressionist method. Yet, at the time, his venture into the Impressionist technique did not figure as a dominant aspect of the criticism of the painting, for the novelty of this method of execution was simply not understood. As Duret noted, the Chemin de Fer in 1874 had scarcely been recognized as an open-air work. That Manet was both familiar with this method and on good terms with its inventors is clear. The year after The Gare Saint-Lazare was painted, Manet went to Argenteuil, where he painted beside Monet and Renoir.

Manet, Boating, 1874

Appearing in the Salon in 1874, this was the first plein-air work to be exhibited in a Salon, but this aspect of the painting—which automatically distinguishes it in history—went overlooked at its reception. For those who had been able to accept the subdued color and relatively precise definition of the Bon Bock, The Railway was a new outrage.1 One after another the reviewers contributed their obloquies to the almost uniform consensus. Here and there a glimmer of sympathy surfaced. Philippe Burty came to the aid of the work that was to receive so much scorn. In the 9 June 1874 issue of La République Française Burty noted the plein-air technique, and he singled out for praise the blue twill frock of the seated young mother. Above all, we recognize M. Manet’s desire to strike the right note without the help of any artifice of style or pose and his application of painting out of doors. Even the painting’s supporters could not bring themselves to unalloyed admiration. In the 19 June 1874 issue of Siècle, Castagnary faltered into a discussion of the work with a sense of dogged exhaustion: Finally, since I am listing the paintings, and so that nothing should be forgotten, there is Manet’s The Railway, so powerful in its light, so distinguished in its color, and a lost profile so gracefully indicated, a dress of blue cloth so broadly modeled that I ignore the unfinished state of the face and hands.

1 – George Heard Hamilton, Manet and His Critics (NY: Norton, 1969) p. 177

Manet, The Gare Saint-Lazare, 1873 (detail)

Thus, Courbet’s supporter mustered only the most categorical and qualified praise for a work that otherwise was not well received at all. The 6 May 1874 issue of Le Charivari mocked the painting and produced a playlet for its readers:

M. Veuillot: It is a case of acute pictorial delirium.

The Executioner: Shall I…?

The Executioner strikes furiously at the bars of the cage.

The Little Girls (laughing): Bad Luck! You can’t get at us. Papa Manet made the bars enormous!

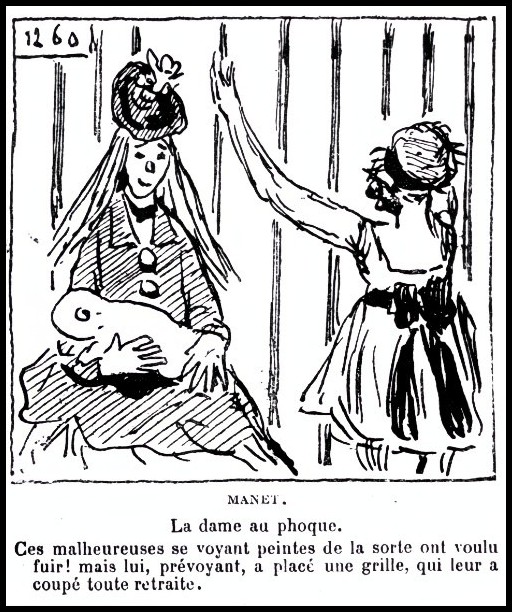

How odd the modern reader finds this note of madness concerning so placid and seemingly inoffensive a painting. The 15 May 1874 issue of Le Charivari echoed this diatribe when the caricaturist Cham declared of the picture: The lady with the trained seal. These unfortunate creatures, finding themselves painted in this fashion, wanted to flee! But the artist, foreseeing this, put up a grating that cut off all retreat.

Cham, La Dame au phoque | Le Charivari, 15 mai 1874

In addition to the ridicule aimed at the picture because of its powerful, and apparently objectionable, composition, the predicament of the two subjects caused further merriment in the press. On 10 May, Le Tintamarre printed a caustic doggerel, which refers to the insane asylum of Charenton: Ce tableau d’un homme en délire / a, pour étiquette, dit-on / ‘Le Chemin de Fer,’ il faut lire: / Chemin de fer pour Charenton (This picture by a crazy man / has been labeled, as intoned / ‘The Railway Train,’ it ought to scan: / Train to Charenton). Yet it is hardly an act of madness, of ‘delirium,’ that we witness, but the coolest, most reserved exposition. Somehow the painting presented a sharp irritant. What appears to us to be docile clearly incited some part of the serious public in Manet’s time. It is all too easy to pity or revile those who disdained the picture, but dismissing the critics does not illuminate the source of their irritation.

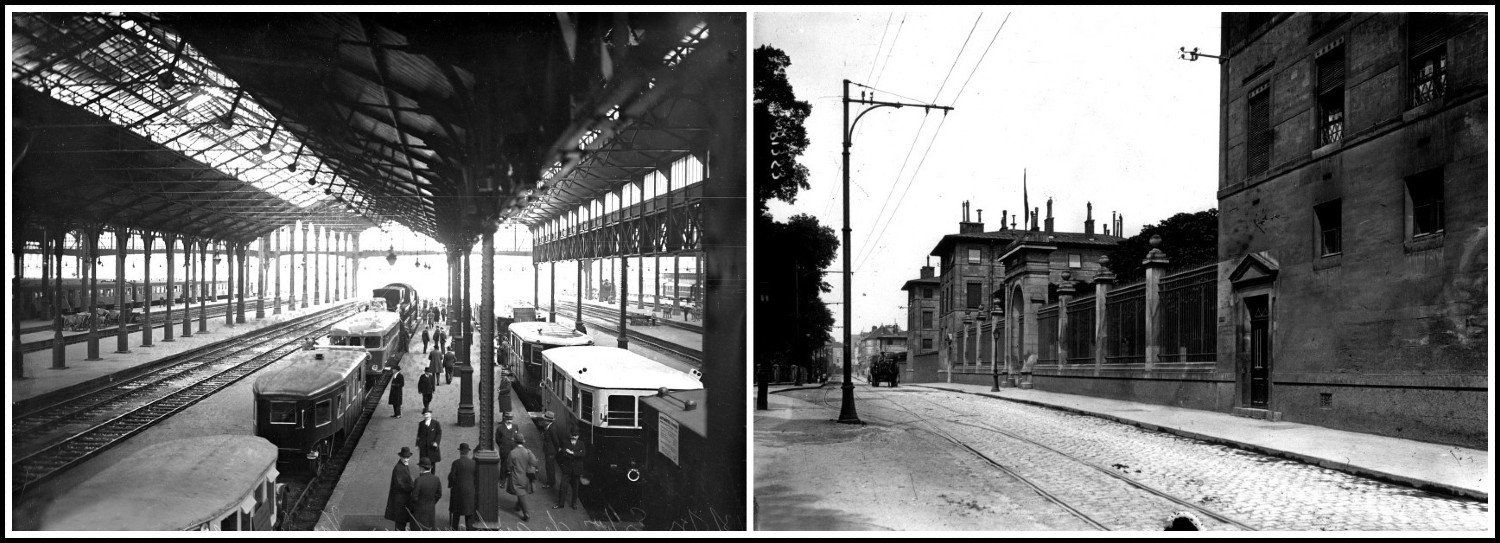

Le Gare Saint-Lazare (BnF) | Asile d’aliénés de Saint Maurice, dit de Charenton (BnF)

This work, which today seems either wonderful as a painting or rather neutral as an excursion into subject matter and which occupies a footnote in art history because of its introduction of plein-air painting to the Salon, meant a great deal to Manet. Indeed, when the time arrived to propose works for the consideration of a juried exhibition held in association with the Universal Exposition of 1878, Manet submitted a list of thirteen pictures, of which nine had already been exhibited at the Salon. One of these was The Gare Saint-Lazare. Manet’s special esteem for this painting was evidenced by how he treated it over the years. Yet, however urgent that communication intended for and repeatedly presented to Manet’s contemporaries, it was not understood either in its time or for several generations thereafter. Nor was Manet the type to rush into print to defend or explicate his paintings. By their consistency and coherence his works had to support their own internal arguments. Even Manet’s great friend and advocate Duret could not fathom this work. Summarizing the painting’s critics, Duret noted: In addition to the objection that the color scheme was too vivid, the subject was pronounced to be unintelligible. Properly speaking, there was no subject at all; no interest attaches to the two figures because of what they are doing. In this remark Duret reiterated, at some distance, what had originally appeared in print in the year of the painting’s appearance before the public. In the 19 June 1874 issue of L’Opinion nationale, Armand Silvestre first sounded the note that would be repeated most frequently up until the present, that The Gare Saint-Lazare was a triumph of style over subject matter: I should understand how one might disapprove of the style of the work and even that one could grow indignant. But what is the problem? What has the painter wanted to do? To give us a truthful impression of a familiar scene.

Manet, The Gare Saint-Lazare, 1873 | Le Gare Saint-Lazare, BnF

To the extent that we may list the details of this scene, that we are able to reconstruct the time and place of its origination or can specify the persons who are depicted, then to that degree the work is indeed ‘truthful.’ Accordingly, the work is not a ‘fiction.’ The models do not pretend to be others, and they do not assume or express other personalities. Indeed, their personalities are not an issue with which this painting is at all concerned (something the painting’s first vexed viewers considered to be an inexcusable omission). The models’ costumes are contemporary, and the place is neither exotic nor historical. Plainness would have been permissible to the academically minded had the work treated contemporary royalty, politics, or those of high station (distinguished by great acts or lucky birth). Liberal factions might have been satisfied had Manet painted the miserable, whose wretchedness affronts us and challenges conscience. Instead, his bland muteness offended most spectators and baffled all. A century later we recognize the situation as a moment in the life of Paris: this is a real garden at an address in the Batignolles quarter; we can know the models’ ages and histories. But such information can never accumulate into a sufficiently large parcel of truth to capture the essential character of Manet’s art.

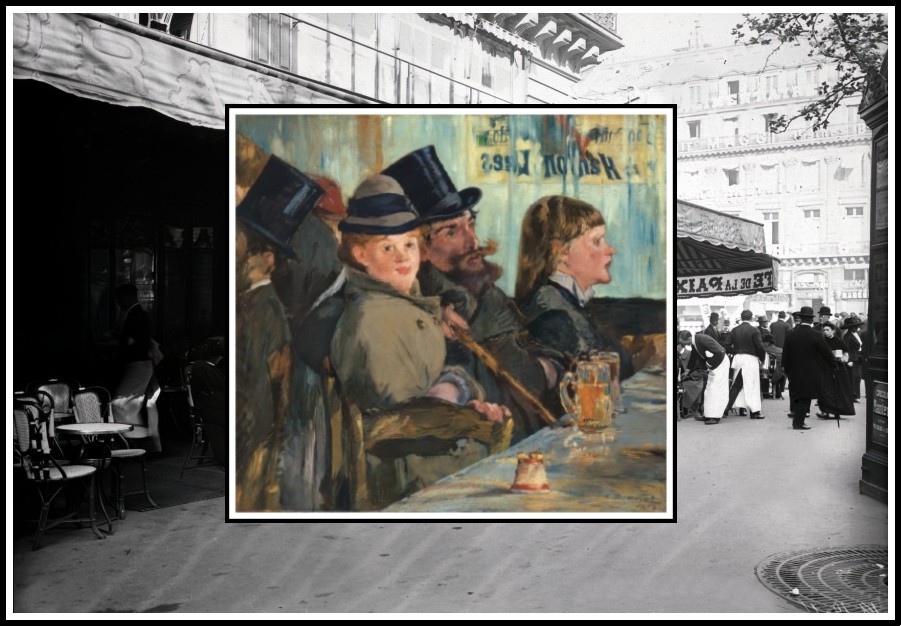

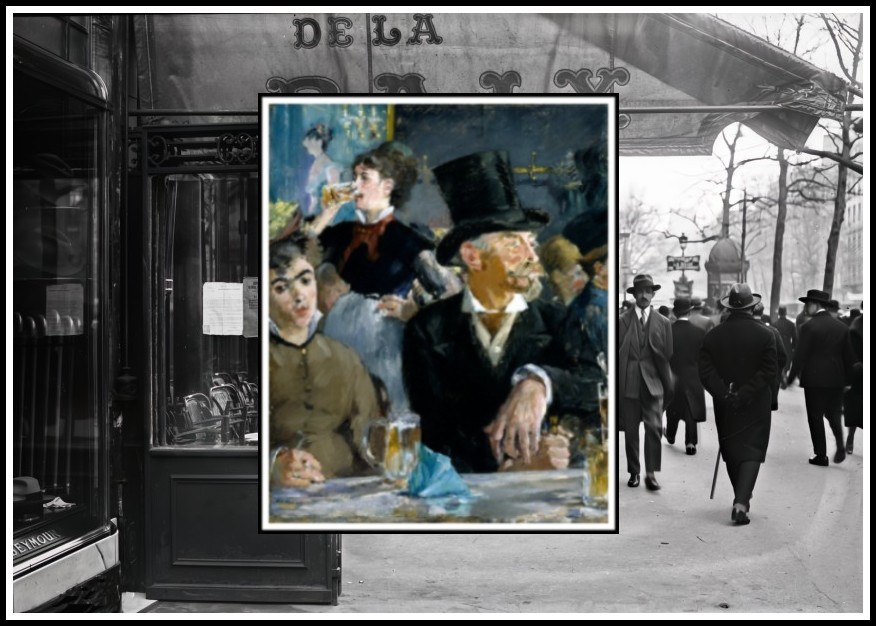

Café de la Paix (BnF) | Manet, Au Café, 1878

His painting absorbed the observational assumptions of the Impressionists, as it had first subsumed the Old Masters, then the frank figurativeness of Realism (so different from what Impressionism would become with the death of Bazille). Manet endeavored not only to include but also to transcend Realism. His ambitions arose from a nominalist and descriptive address to the world (denotation), but Manet arranged appearances so as to surpass an inventory of the world and to mean (that is, connotation). The nominal truth of the situation can be inventoried as a list of portrayed things, but that meager honesty pales beside another truth that governs the disposition of the painting’s deep relationships. That other truth, in its grand ambition, abides beyond the imagining of the work’s early viewers. The plain representation of an instant in the swirling activity of nineteenth-century Paris does not, despite the obvious superficial veridicality of the painting’s description and despite the charm of the painting, reveal why this scene had to be painted. Appearances notwithstanding, it was the relationships between the figures themselves as well as between the figures and their environment—contrived relationships that could not have been more clever or more exquisitely adjusted—which occasioned the painting. In The Gare Saint-Lazare’s only partially sensed implications lay the offense to Manet’s own public.

Café de la Paix (BnF) | Manet, Au Café-Concert, 1879

III. TO THE GARE SAINT-LAZARE

Eugène Delacroix in his Journal, 21 May 1853: After having examined these photographs of nude models, some of them poorly built, overdeveloped in places and producing a rather disagreeable effect, I displayed some engravings by Marcantonio [Raimondi]. We had a feeling of repulsion [at the photographs], almost of disgust, at their incorrectness, their mannerism, and their lack of naturalness; and we felt these things despite the virtue of style. Let a man of genius make use of the daguerreotype as it is to be used, and he will raise himself to a height that we do not know. Down to the present this machine-art has rendered us only a detestable service: it spoils the masterpieces for us, without completely satisfying us. Delacroix’s adamant challenge—to build upon a new confidence sprung from an as yet unknown faith—was expressed in all his work. His charge was taken up by Manet who, as we know by the history of his copying, envisioned Delacroix as the foremost exemplar of grand painting. That generational connection, its nature and expression, is less easily specified in particular works. Hardly ignored by recent scholarship, The Gare Saint-Lazare, proffers the ideal opportunity for a test reading precisely because on first viewing it does not seem part of the rich allegorical network affiliating much of the rest of Manet’s production. In fact, it proves to be one of the special works of his career, functioning as a keystone for the assumptions supporting his mature production. As we shall see, Manet himself probably considered The Gare Saint-Lazare to be one of his most important works.

Manet, The Gare Saint-Lazare, 1873

The picture was under way as early as 1872, when it was seen in Manet’s studio, where he sketched in the basic composition. Its conception thus preceded Manet’s venturing out and setting to work in front of his models. It is entirely possible that the composition was established in a posed tableau vivant that Manet had photographed as the basis for this work. Gabriel Weisberg notes that while no specific photographic source has come to light, the impact of this medium (then also a craze in Paris) cannot be underestimated in helping Manet toward the final realization of his composition. Photographic instantaneity—the perfectly isolated moment hewn from the flow of time—attracted painters from the moment of its appearance.

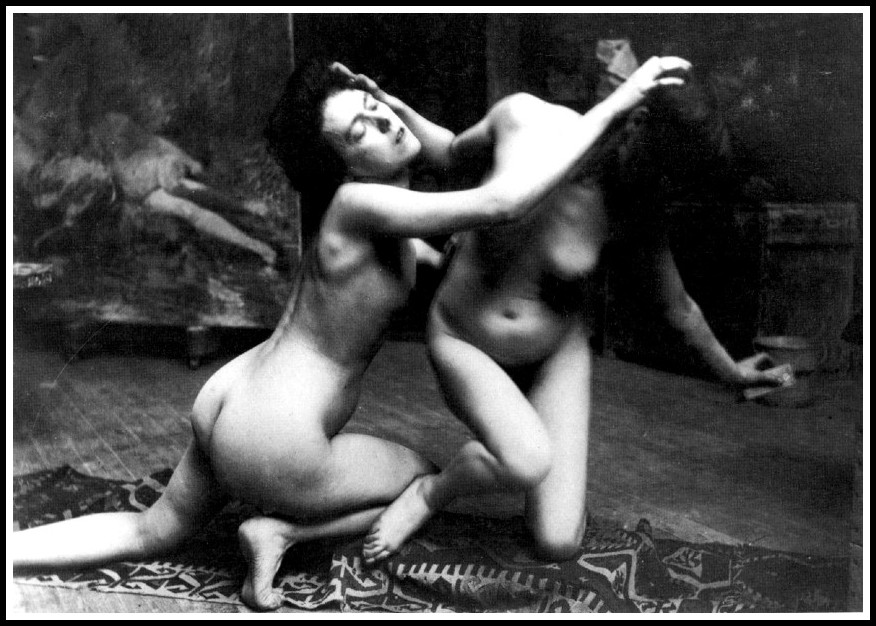

Models posing for Falguière’s Bacchantes, 1886

A generation before Manet, in Delacroix’s time, new terms were being devised. Théodore Géricault’s huge The Raft of the Medusa, 1819, depicts a singular moment in the story of a naval, human, and national calamity. The spectators’ knowledge of those circumstances must serve as the basis for appreciation of Géricault’s selection of that instant. This narrative’s highpoint comprises one of the principal affective elements of that work. Ultimately, however, as the scene is embedded within the flow of a story, Géricault’s work—however daring in scale, artistic conception, and political audacity—remains essentially a history painting.

Théodore Géricault, The Raft of the Medusa, 1819

Similarly, Delacroix’s The Barque of Dante, 1821-22, depicts one moment in a narrative. Soon after executing this work, however, Delacroix began to question the fundamental character and assumptions of history painting. In comparison, the maturing Delacroix speculated on the ‘length’ of the instant, as he sought to compress narrative into a single representative construction.

Eugène Delacroix, Dante et Virgile (La barque de Dante), 1822

Scenes from the Massacre on Chios, 1821-24, arose from Delacroix’s urge toward the non-narrative, which same tendency gave birth to photography. Under the aegis of that (photographic) aesthetic, Delacroix sundered the progress of a story in order to present a single, synthetic moment that combines many separate incidents heaped together to form something like a sculptural monument. The distance traveled from The Barque of Dante to Scenes from the Massacre on Chios distinguishes that essential difference between the painting as the depiction of the critical moment in a story known to the spectators and the painting as an independent construction. The former epitomizes illustration and relies on an external, textual source, while the latter is a self-reliant entity that comments on its sources (that is, it reconfigures its sources to comment upon them). Under the hand of Delacroix, painting assumed a life parallel to, but no longer submerged within, the fabric of a ‘text’. Autonomous, painting could now surpass its role as a colophon to literature, although Delacroix was not to realize this potential.

Eugène Delacroix, Scènes des massacres de Scio, 1824

Inheriting the implications of the painting as an uncontingent creation, Manet relied on the documentary authority of the photograph’s aesthetic, its instantaneity. He may have actually depended on photographs for his composition of The Gare Saint-Lazare. Saturated with the most advanced thinking of its time, The Gare Saint-Lazare arises from photography’s nascent aesthetic and its sibling philosophies, Realism and plein-air painting. The Gare Saint-Lazare was executed out-of-doors in the garden of Manet’s friend and fellow artist Alphonse Hirsch. It was not Manet’s first plein-air painting however; in 1870 he painted In the Garden which depicts the backyard of a Parisian house (16 rue Franklin, the home of the Morisot family). In the foreground, Tiburce Morisot (Berthe’s brother) reclines on the grass, lending a kind of casualness to the work we would recognize today in a snapshot. Charles Moffett observes that the seemingly random character of the composition is integral to its convincingness. The partially blocked figure of the man contributes significantly to the sense of realism. At first, he seems to have been included simply because he was there, like an extraneous or incidental detail in the background of a photograph; but on closer examination he is seen to affect the mood and possibly the meaning of the painting. It was probably his presence that led Theo van Gogh, in a letter to his brother Vincent, written in 1889, to remark: ‘This is certainly not only one of the most modern paintings, but also one in which there is the most advanced art. I think the pursuits of Symbolism, for example, need proceed no further than this canvas, in which the symbol is uncontrived.’

Manet, In the Garden, 1870

Thus, nineteenth-century observers attest that In the Garden unites plein-airism’s apparently informal verisimilitude, photography’s potential for casualness born of factuality and, paradoxically, Symbolism’s utterly unstraightforward cleverness. A compact masterpiece, this unassuming and gentle work won new territory for modern art. Inconspicuously, the picture pointed the way to other uses for plein-airism’s potential—to insinuate the appearance of documented existence into artifice. While In the Garden was the first of Manet’s works painted fully in the open air, The Gare Saint-Lazare was probably the first plein-air painting ever shown in a Salon. Today, more than a century after the Impressionists revolutionized art by painting at the scene of their observations, plein-air is a commonplace. For Manet, however, painting The Gare Saint-Lazare outdoors created problems. This choice of an open-air setting added to the misunderstanding of the painting and contributed to the myth of his naïveté: The oldest and most persistent of the alleged weaknesses of the painter, his lack of imagination, originates with his confession of his need for a model.1 The Gare Saint Lazare’s dutiful record of an out-of-doors setting did not exhaust Manet’s ambitions for this configuration. A secreted libretto animates the apparently neutral and inactive scene. The scene’s location contributed to the work’s meaning. Hirsch’s garden overlooked the railway cut. Behind an iron grating at the rear of the work the steam and smoke of a passing train obscure the tracks and, indeed, any view of the train.

1 – George Mauner, Manet: Peintre-Philosophe, pp. 2-3. Mauner notes that ‘Manet himself, by his words and deeds, has contributed substantially to this confusion’.

Degas, Le Peintre Alphonse Hirsch, 1870

To attempt a major work of ambiguous exposition, at one moment forthright and in the next instant self-consciously mired in the conventions of his art, Manet repaired to familiar supports. Victorine Meurent, who had now been Manet’s model for a decade, posed as the young woman. In addition to her long association with Manet, Mlle Meurent may have worked for Manet’s seniors [painters], as Farwell notes: Among the unbound photographs of the nineteenth century preserved at the Bibliothèque Nationale is a group by Quinet, lithographic editor, in 1852 and 1853, representing a model in various poses and various degrees of undress who is almost certainly Victorine Meurent. If she is Victorine, this would constitute evidence, besides that of her posing for Manet, of the class of woman to which she belonged. Moreover, she would have to be at least 17, perhaps 20, in these photographs in 1852-3, making her 27 to 30 in 1862-3. This does not seem inconsistent with the way she looked when Manet painted her for the first time. It would also account for her looking so much aged in The Railroad [The Gare Saint-Lazare] in 1873, when she would by this accounting have been 37 to 40. Assuming this model to be Victorine, another interesting fact surfaces: she is the model whose likeness in the hands of Delacroix became the small Odalisque of 1857. Delacroix owned at least two prints of her, in one of which the model is in the same pose as the Odalisque. We have then the remote possibility that Victorine Meurent regaled Manet in 1862 with reminiscences of posing for Delacroix, even though only for the photographer.1

1 – Beatrice Farwell, Manet and the Nude: A Study in Iconography in the Second Empire (originally a Ph.D. dissertation, UCLA, 1973) (New York: Garland York, 1981 ), pp. 161-162. Of course, this tie to the past would have been exactly the sort of connection that Manet would have most sought out. More convincingly than the supposed harsh charm of her features, Victorine Meurent’s link to Delacroix could have proved an irresistible attraction as a bit of living history.

Eugène Durieu, Modèle assis de face, 1854 (BnF) | Eugène Delacroix, Odalisque, 1857

Hirsch’s daughter, Suzanne, posed as the little girl. (The two figures are not a mother and daughter, as sometimes thought. The idea seems to have started with Philippe Burty.) For some viewers the work’s subject was simply portrayal. Anne Coffin Hanson noted that works like The Railroad and The Conservatory are portraits in the sense that they fulfill [art critic] Castagnary’s aim and allow the spectator to use them to reconstruct an epoch.1 What the character of an epoch might be, or might have been, touches precisely upon the job of the art historian, since the ‘epoch’ is a historical model. At least superficially, we can suspend the obligations of history and genially concur with Duret who noted that ‘Manet was the painter of real life.’ But to accept at face value this work’s documentary potential to illuminate the past, unattended by critical history, puts us at the mercy of a gentle evocation. Unfortunately, this method of deriving our notion of the nineteenth century eventually would be discovered to have produced a very different image for each of us—lovely poetry but not expositional history.

1 – Anne Coffin Hanson, Manet and the Modern Tradition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979) p. 77

Manet, The Conservatory, 1879

If The Gare Saint-Lazare merely presented the opportunity for portrayal, Manet’s ambitions might have been fairly simple. Painters need no excuse to exercise their art in adulation of light and women in the city. To the degree that he dealt with specific, particularized depictions, Manet engaged portrayal; when he generalized, he engaged in allegory or general history. These figures might have been but objects that he exalted by selecting them as the target of his painting so that the women are not mere images. Manet has given them a personality and a background of their own. And above all, he relishes them as he would ripe fruit.1 There is no diminishing either the sensuality of Manet’s painting, or his sensuality as an observer. Yet what we know of Manet’s treatment of subject matter in other works, the sources he tapped, as well as his approach to the profession of painting suggests an enormous seriousness of purpose. A vision of his massive artistic responsibility should restrain Manet’s commentators from assuming that any vague, hasty, or frivolous intention might have compelled such work. Still, viewers would hardly suspect that Manet’s focused artistic concerns posited grand meaning for The Gare Saint-Lazare.

1 – Courtion, Edouard Manet, p. 10. Earlier in the same passage, Courtion reveals his prejudice that ‘today when I think of Manet, who painted luminous flesh and shining eyes in the world’s loveliest light, I seem to see a veritable procession of delectable women.’

Manet, Victorine Meurent, 1862

If one conceives of subject matter in terms of narrative or portrayal, for example, then certainly nothing like traditional subject matter appears in this picture, and Duret would have been right in assuming that nothing was transpiring in the painting. The issue of narrative construction would not have arisen for Manet’s contemporaries, because the painting does not seem pertinent to storytelling at any point (except that through such stillness, reductionism, and narrow focus Manet may have questioned the very limits of narration). Modern writers have not engaged this work as narrative in either a traditional or a special reading. To recount either a fictional or actual event in art, the spectator and the artist must share a sufficiently broad understanding of the subject for the recognition of characters, sequence of events, and action to be legible through the chosen style. Generally, the visual arts cannot tell a story, but the viewer can be reminded of an event or sensation. Since these are not portraits of celebrated personalities, the spectator brings no associations to this work, and there is no obvious storytelling occurring. The frustration of Manet’s critics was complete. The Gare Saint-Lazare was neither portrayal in any traditional sense nor recitation of any obvious event. Depicted things (a portrait, still life, or landscape) can refer back to the style of depiction and can thus identify a métier. The Gare Saint-Lazare does not obviously describe motion (a local gesture) or process (an allegorical generality), nor does it offer the overt performance of an ‘action’ that transforms the situation (a localized incident of which narrative is built). It neither names any self-evident cluster of things nor does it tell any evident story. The painting can thus be likened to neither a noun nor a verb.

Manet’s The Gare Saint-Lazare ‘can be likened to neither a noun nor a verb’.

RELATED POST IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2024 | All rights reserved

Comments