An In-Depth Analysis

MANET’S CONTEMPLATION AT THE GARE SAINT-LAZARE – PART 2

Harry Rand

Posted by kind permission of Harry Rand, Art Historian, former Senior Curator of Cultural History at the Smithsonian Institution

From Harry Rand, Manet’s Contemplation at the Gare Saint-Lazare (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987 (pp. 3-49)

THIS IS PART 2 OF THE ESSAY. TO GO TO PART 1, CLICK MANET’S CONTEMPLATION AT THE GARE SAINT-LAZARE – PART 1

Edouard Manet, BnF (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

IV. AT THE GARE-SAINT LAZARE

To grasp the full import of this painting, we ought to begin by simply cataloging its subject matter without imputing motives to the portrayals or injecting relationships (that is, traditional narrative relationships). The picture does not inform us concerning the personalities of its subjects, a fact with which we must at first reconcile ourselves and which will later prove to be a pivotal feature of the work. Created, or willed, relationships for the figures (unsupported by evidence in the painting) would supplant whatever actual concerns may underlie the picture. Biographical research could reveal the personalities that animated Victorine Meurent and Suzanne Hirsch in life, but such information was not generally known to Manet’s spectators and was therefore probably not a major component of the work. Surely, Manet was engaged by a challenge that surpassed the inventing of plastic expressions for individuals already knowable to his audience (that is, caricature). The temperaments of the depicted individuals are not part of the picture’s significant cargo. Exactly this lack of overtly expressed personalities—a trait typical of much of Manet’s work—distinguishes this painting. Revoking so many possibilities for drama, Manet (and his work) appeared singularly devoid of a limber wit or agile intellectual faculties. We may initially suppose, as Zola did, that Manet was an unthinking painter.

Étienne Carjat, Portrait d’Edouard Manet, BnF

To impute serious ambition to Manet, we must attend to the actual disposition of things within the work. To construct psychology for the subjects would oust the painting’s ample self-evidence for a false notion. The resulting narration, forcefully insinuated for the convenience of the perplexed spectator, would link the two figures in a web of meanings, endlessly arguable and utterly without pictorial foundation. Yet to subtract the possibility of this sort of consideration would make the picture so bereft of traditional subject matter that it begs the injection of some outside supporting matrix in order to diminish what appears, in a superficial reading, to be nothing but commonplace and inconsequential. This dilemma greeted the painting’s first critics; we know their response. Subsequent spectators have appreciated the paint handling and controlled light in The Gare Saint-Lazare without questioning Manet’s objectives for the work. Remarkably, reciting a detailed inventory of the painting’s subject matter reveals the components of a compelling argument. A plain reading of the depicted situation thus allows us to measure the range of concerns of The Gare Saint-Lazare. Arising from the firmest of sources—the work itself—the disclosure illuminates something of Manet’s intentions and his interests when he composed the picture.

Alphonse Leroy, Edouard Manet, BnF

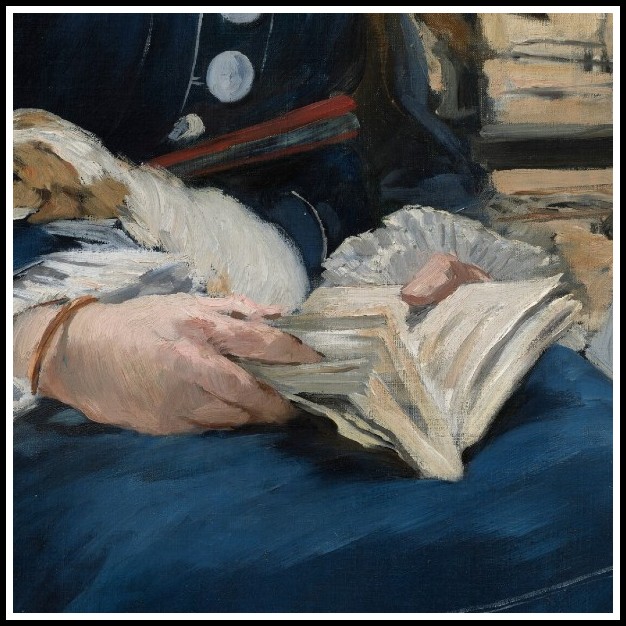

V. AT THE GARE-SAINT LAZARE: A LADY AND HER BOOK

We can begin the inventory of the painting’s subject matter with the dominant figure of Victorine Meurent. Fingers interleaved in a book, she had been reading with great concentration and seriousness. Not only are the pages held open to what lies directly before her but she also marks another place with the index figure of her right hand, perhaps another with her left index finger, and possibly yet a different page with her right thumb. As if in a close reading, she had been moving back and forth through the book, perhaps comparing passages, consulting a footnote, examining illustrations, or weighing the merits of one poem against another. Clearly, she was engrossed. Her reading insulated her from the roar and hiss of the trains passing behind her and from the usual street noises. Oblivious to the noise, she followed the intricacies of the text (although her focused concentration on reading also admitted an unconscious awareness of the child’s safety). Yet something has wrested her attention from reading: when we encounter her, Mlle Meurent raises her eyes at our presence and stares out toward us, perhaps recognizing the spectator, perhaps not. She is now alert. Her attention which has expanded from the closure of intensely focused reading to embrace the wider field of which we are a part (but only a part) is now free to swing in a wide arc that embraces all of Paris, the street before her, the noise of the railyard behind, and potentially everything else in the visible world. None of this activity and wealth of sensation, so apparent to the spectator of the painting, would have been noticed by her when she was submerged in her text. An instant before our ‘appearance’ her eyes had scanned the pages of her reading and now she looks at us through the space of the painting.

Manet, The Gare Saint-Lazare, 1873 (detail)

VI. AT THE GARE SAINT-LAZARE: THE CHILD AND THE BUNCH OF GRAPES

If Victorine Meurent’s interrupted attention to her volume describes one sort of concentration, a more diffuse and perhaps deeper kind is represented by Suzanne Hirsch, who stares through the iron fence into the steam. Only a railroad shed in the middle right might distract her attention. There, two tiny figures are placed, one in the door of the shed and the other striding toward the right. But the child pays no notice. Instead, she looks down and to the center, into the very swirling heart of the steam. Unlike the adult, the little girl ignores our gaze. Her back to us, Mlle Hirsch is painted with a lost profile, and we can only suppose her features. She is rendered anonymous, her features general. We share something of her musings as she stares into nothingness, since we can only guess at how she absorbs that imprecise and steamy image. Once before Manet had employed the lost profile for a central figure, also a little girl, in The Old Musician, 1862. Holding an infant, the ragged waif on the left looks back, into the center of the composition. She, who may have been a gypsy, meets the gaze of other figures within the painting, and an internal resonance is established, knitting the whole together. Unfortunately, the rest of the composition is too flimsy to really bond the other figures. The work is often described as treating alienation and displacement, which may be the case, but the figures’ isolation and their lack of artistic integration bespeak Manet’s limited powers in the early 1860s more than it does alienation.

Manet, The Old Musician, 1862

By the time of The Gare Saint-Lazare, Manet had mastered his compositional problems regarding the placement of self-absorbed figures in proximity. In place of the exchange of glances in The Old Musician, The Gare Saint-Lazare richly affiliates many kinds of eye contact to engage us, the painting’s viewers. Prominent in this repertoire of devices that modulate sight is the lost profile. For the spectator of the painting, the face (and identity) of the beholder of the steam are unseen, and one imprecision symmetrically matches another: the drifting blank cloud, without describable shape (and therefore simply a ‘type’ [cloud]), has been given its perfect equivalent in the child’s missing expression. Suzanne Hirsch is known to us only in a generic sense, as a little girl dressed in a certain way. Although her lost profile might have been coincidental or required by the composition, in this context her gesture of turning away complements and amplifies Victorine Meurent’s attentiveness.

Manet, The Gare Saint-Lazare, 1873 (detail)

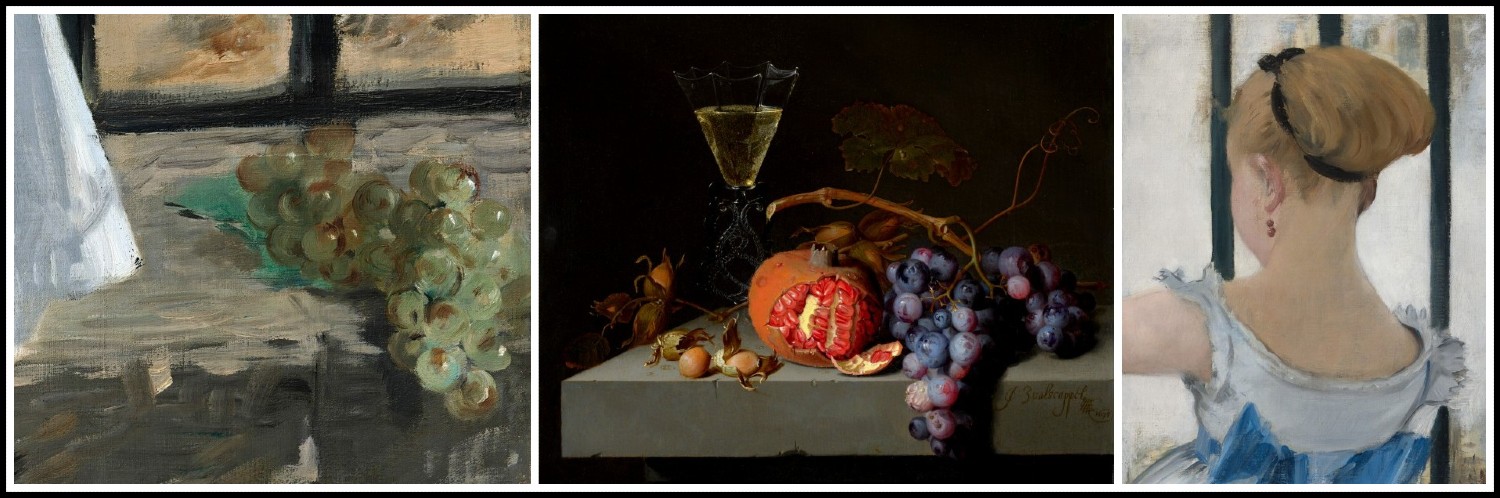

Similarly, the bunch of grapes placed near the little girl indicates that she has been (absentmindedly) eating. Whatever the compositional demands of the scene, the grapes are not placed between the figures to imply that they are being shared. Rather, they lie at the extreme right of the painting, where they are as much an ‘attribute’ of the child as the book is of the adult. This snack of fresh fruit has been brought to satisfy the cravings of the youngster, who cannot distract herself by reading. Just as she exhibits a lost profile, the child also exhibits a ‘lost gesture’: her right hand, perhaps still holding a grape, is raised to her mouth. As we must invent her face, we must also imagine her gesture. In contrast to reading, with its conscious, deliberate, and conventionalized symbols for the adult’s pleasures, the child is absorbed in unnameable cares. Even more certainly than the mathematical relationships of music, which seem so abstract in comparison with the other arts, the symbolism of taste is totally abstract and non-objective in that it refers to nothing else. Manet essayed the contribution of the senses as attentively as he construed the other elements of the work.

Manet, The Gare Saint-Lazare, 1873 (detail)

The totally interior, saporific1 universe tasks the visual artist to create images that suggest taste. The intimate emotions engendered by seeing, which challenged the Impressionists, are subject to communal verification at a distance; we can point at what we see, requesting confirmation. Taste, however, locates an intimacy much less subject to substantiation. Manet eloquently matched the quality of taste, the perception of flavor, with a figure whose features remain unknown to us. We espy the girl engaged in complete self-absorption, committed to the most personal of perceptions. Her nibbling from the bunch of grapes proposes a thoroughly mental, interior, non-discursive, and phenomenally absolute set of considerations.

1 – The quality in a substance that is perceived by the sense of taste; flavor.

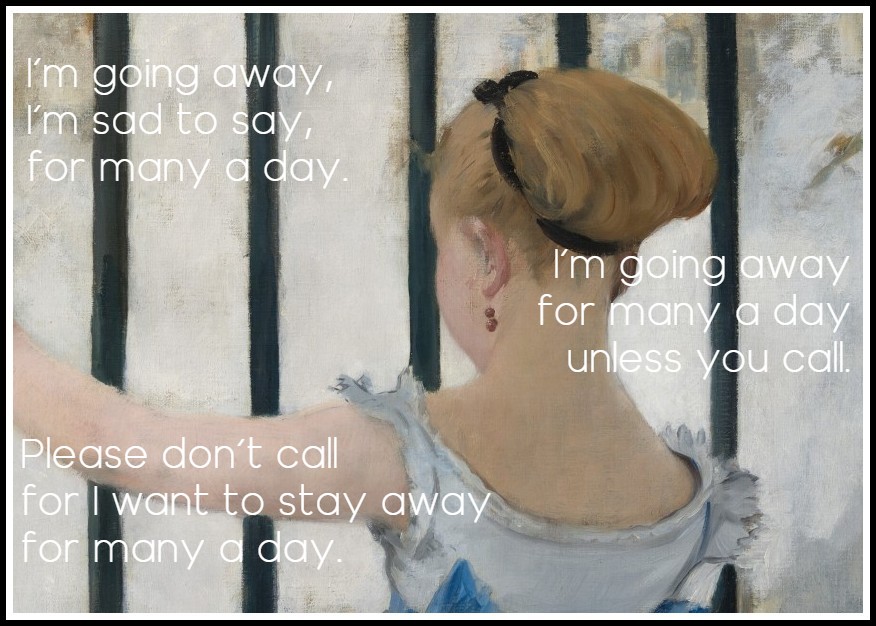

Manet, The Gare Saint-Lazare, 1873 (detail) | R.D. Laing, Conversations with Children (Penguin Books, 1978) p. 39

To picture the consumption of food is to show a coarse bodily function. Indeed, so strongly corporeal is eating that scenes of eating and drinking have been employed throughout the history of Western art to show rowdiness, drunken good nature, and to accompany lust. Certainly, one of the supreme expositions of the mischievous effects of ‘the grape’ is Diego Velázquez’s Los Borrachos, c. 1628 (‘The Drunkards’), in which a young man, crowned as Bacchus with vine leaves, bestows a leafy coronet upon one of his ‘followers.’ In fact, this mock-classical scene depicts a group of deeply inebriated contemporary Spaniards in every range of reaction to insobriety. A full spectrum of reactions to drinking is essayed, from leering riotousness, to introspective (if temporary) self-reproach, to momentary religious experience, to stupefaction. This amazing early work by Velázquez was a special favorite of Manet’s.

Velázquez, The Feast of Bacchus (‘Los Borrachos’), 1628-29

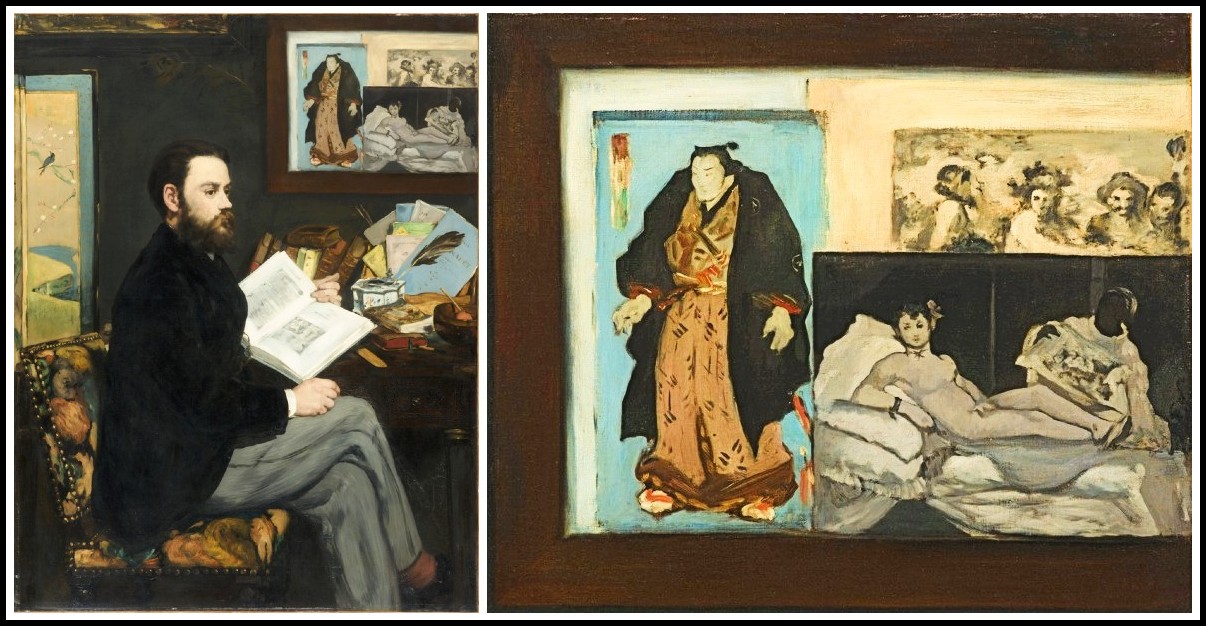

Although Manet seems never to have copied the work in oils, its image peers centrally from his Portrait of Zola. The appeal of Los Borrachos to Manet may have stemmed from its remarkable conceptual program, which spanned the total range of psychological reactions to wine.

Manet, Émile Zola, 1868

As the adjunct to religion or in regard to ritual meals, eating’s baseness can be set aside, as in paintings of the Last Supper, or of the Supper at Emmaus. Otherwise, it seems impossible to depict the act of eating and still solicit the ethereal qualities and ephemeral sensations of aroma and taste. Manet solved this problem by showing someone not eating but only suggested as eating. The sheer savor of food and the indescribable sensation of tasting fruit can enter the iconography of art, but only with the most exquisitely careful preparation of a scene. The figures’ contrivances suggest that Manet wished to invoke this impalpable world of taste as part of a greater scheme. A range of sensations passes through the little girl, from her tangible, sure grasp of the iron fence (touch), to her lost profile as she observes the steam (sight, both outward and inner), to her lost gesture of raising the fruit to her mouth (taste). The paradox of a spiritual state, represented by the coarsest sort of absentminded consumption, recalls analogies of carnal love extrapolated qualitatively—and sometimes by an order of magnitude—to represent divine ardor (a prime example are the apologias for The Song of Songs’ canonical status). The Gare Saint-Lazare’s representation of simple consumption was meant to connote something beyond the literal depiction. Thus, it does not ‘stand for’ another state in a simple one-to-one substitution of a symbol for an idea. The child’s nibbling of her grapes animates a richer situation than what appears superficially to be a mildly innocent portrayal. The graphic prominence of the bunch of grapes (lying separated on a ledge, the center of its own circle of compositional focus) suggests, however tentatively at first, the classical world. Another level of references is thereby introduced: literary symbolism.

Manet, The Gare Saint-Lazare, 1873 (details) | Jacob van Walscapelle, Still Life with Fruit, 1675

This nibbling, a tantalizingly unseen (corporeal) act, embraces a wide range of implications. Its very absence from the apprehensible front of the image robs it of the specificity that would contain and limit the gesture’s possible pictorial alignments. The motif can suggest an analogy to immaterial things, to a certain aura of the past, as well as to the child’s interior psychological world. All these different readings, simultaneously sustained and mutually supportive, hover before us because of the context within which this image occurs. So resonant is the image (of the inviting and archaic icon of the grapes, whose taste we know, and of the little girl who consumes them, whose face we do not know) that once we fix upon this arresting contrast we must disenthrall ourselves from these two related elements. Together the (unseen) gesture and the object (grapes) compound a new specific meaning, realizable only by this ideographic combination. Each constellation of images in the picture resounds until it suggests other states wholly removed from the original condition, and no one motif by itself asserts that world of relationships which unites the entirety of The Gare Saint-Lazare. Together these frank pictorial elements compound a richness that supports the entire painting as a prime example of the Symbolist mentality.

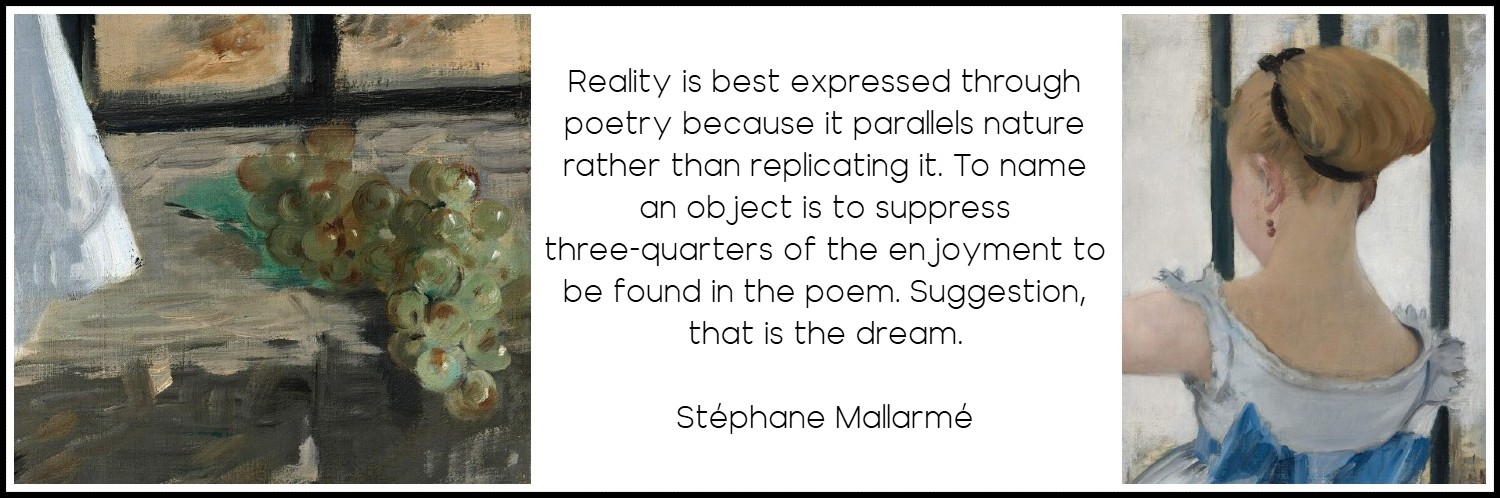

Manet, The Gare Saint-Lazare, 1873 (details) | Stéphane Mallarmé, The Symbolist Ethic & Aesthetic

VII. SYMBOLISM ESPIED

Emile Bernard: What then was the end proposed by pictorial symbolism? The same as that proposed by literary symbolism: to unite form and content while at the same time raising the work of art to a level to transcend idealism. In the Gare Saint-Lazare, Manet interrupts reading to remind us of what the absorption of reading is like. Not showing us the act of eating he reminds us of flavor. He contrasted reverie and attention to induce the feeling of concentration. Neither describing ideas with traditional allegory nor presenting emotional states by dramatic poses, Manet suggests ideas and emotions. All of this was accomplished by means of otherwise unexplained symbols, symbols outside the flow of a narrative and uncodified in emblem books. This formulation of unique imagery rests at the core of Symbolism as practiced by poets. The introduction to The Gare Saint-Lazare’s construction recalls Mallarmé’s words about his special, purposely concise techniques for summoning memories in order to reawaken in the reader stirrings far beyond the apparent powers of text: One must always cut the beginning and the end of what one writes. No introduction, no conclusion.

Manet, The Gare Saint-Lazare, 1873 | Nejc Soklič, Train Station Goodbye, 2021

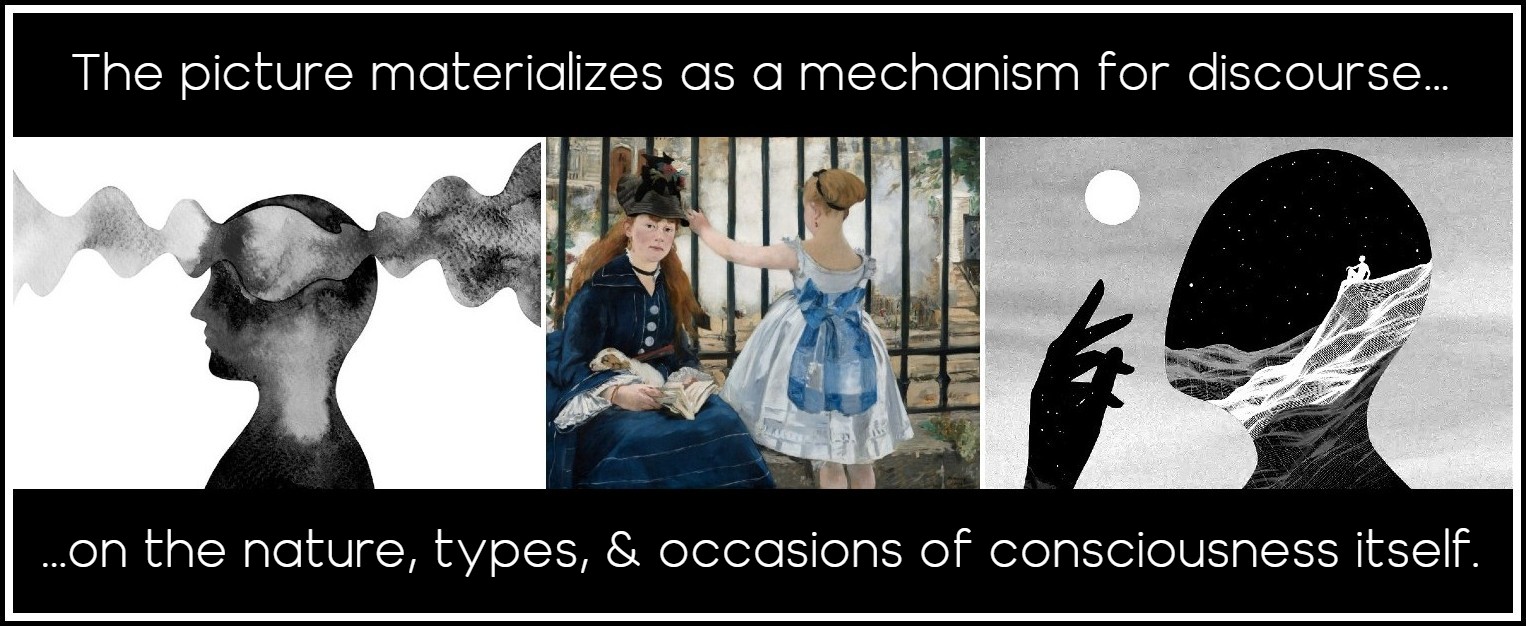

Manet’s compositional intelligence, which had once borrowed from disparate sources to construct a dialogue with painting and history, now combined diverse occurrences in his own world to form a synthetic meaning of a higher order than the original elements could by themselves conduce. The different forms of the two models’ attentions have each been perfectly assigned, although first appearances do not suggest a complex symbolic program for the painting. The contrast between the two figures is not that of pure opposition, with an isometric balance of one trait for another, a dialectic of only two contrasting sets of considerations. Rather, The Gare Saint-Lazare affords the occasion to examine many points within an enormous stratified range of behavior. In the painting’s every aspect Manet expended extreme care to afford counterparts for each level of consciousness. Accordingly, the picture materializes in its entirety as a mechanism for discourse on the nature, types, and occasions of consciousness itself.

M.I.T. McGovern Institute: Consciousness | Manet, The Gare Saint-Lazare, 1873 | Oska, New Scientist: Consciousness

Victorine Meurent’s book, with the white of its pages—vessels of meaning with the potential to convey all the world of ideas, of discursiveness—is utterly differentiated from the girl’s reverie. If the child’s state were exhibited by an adult, we might call it meditation, for it is wordless and expunges the ego. These different measures of consciousness might at first be taken to represent a thematic coincidence. But certain symmetries begin to appear, such as the obvious spatial one in which the adult turns toward us, and out of the painting, while the child turns away, into the picture and its blank world. Not coincidentally, the child stares raptly at the ‘blanc’, the white emptiness. An emissary, perhaps from the white world, the child wears white with a blue sash; the adult is attired in exactly the opposite colors, blue with white highlights. Were this opposition of states of mind (as well as a third condition, that of the adult’s absorption in reading) happenstance, Manet’s intentions for The Gare Saint-Lazare would not be indicated clearly enough to fashion a case for his methodical calculation. But the insistent reinforcement of the theme of consciousness and the spectrum of its various states appears throughout every part of the painting.

Manet, The Gare Saint-Lazare, 1873 (details) | M.I.T. McGovern Institute: Consciousness | Oska, New Scientist: Consciousness

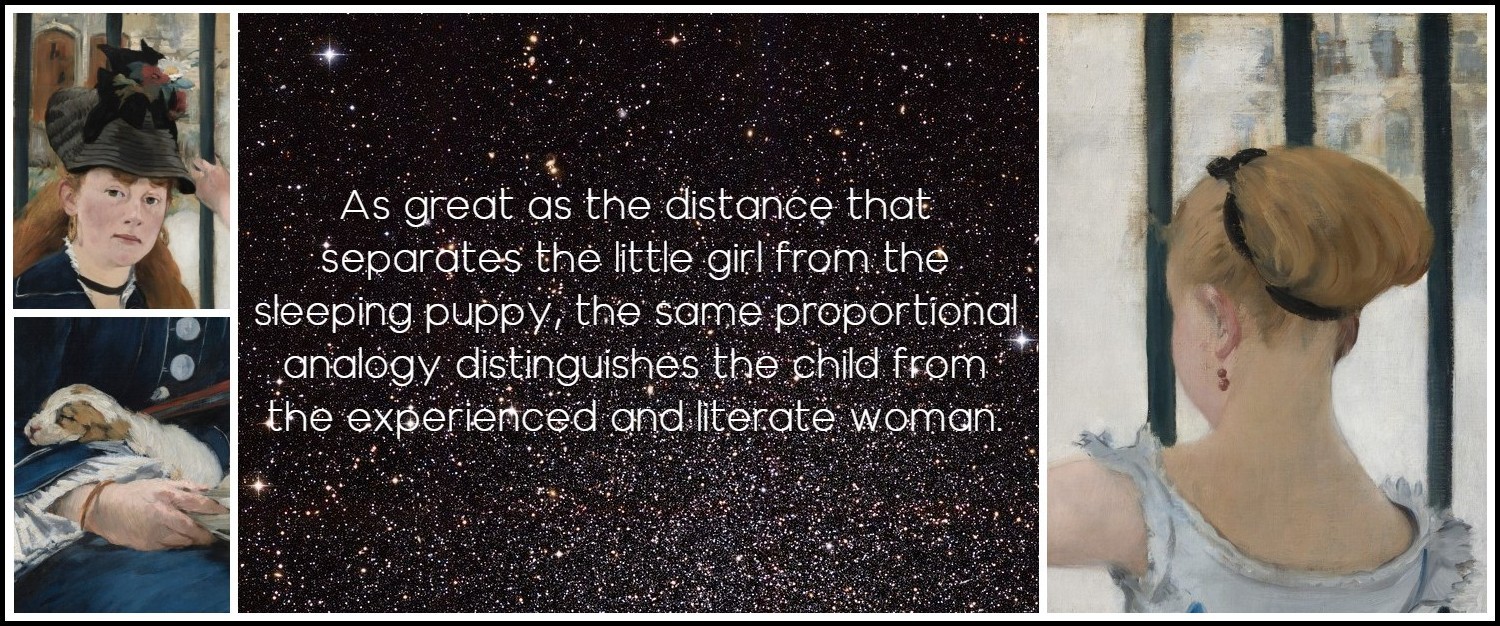

VIII. AT THE GARE SAINT-LAZARE: A CREATURE DREAMS

Even more intangible than any waking state, however meditative or diffuse, is sleep, and in sleep lies the great mystery of the dream. This condition dwells beyond discursive knowledge, although we attempt reconstructions when we return from that distant country. With words, we try to piece together the meanings of dreams that are prelinguistic, or protolinguistic, and that both generate a symbolism beyond our waking capacities and order those symbols in a grammar that is elusive and rare. To complete the graph of consciousness—which peaks with the high noon of adult wakefulness, descends through the concentrated field of the adult’s reading and its directed imaginings, and then dips into the world of a child’s thoughtless nibbling at her grapes and into her wandering attentions—the dream would have to be accounted. And how much more profoundly dreamlike, mysterious, more unknown (and unknowable, since it lurks outside the very possibility of linguistic retrieval), are the dreams of an animal, and not just any animal, but a baby animal, a puppy, its own consciousness a blank. What are the dreams of a puppy? Fresh and newborn, it is both uninformed in its canine world and impossibly distant from the human imagination. In its sleep—thrice removed from us, by slumber and dreaming, by species, and by infancy—it occupies a state we cannot know. As great as the distance that separates the little girl from the sleeping puppy, the same proportional analogy distinguishes the child from the experienced and literate woman—who may, to express herself, call upon all the inventoried creations of world literature.

Manet, The Gare Saint-Lazare, 1873 (details) | The Sculptor Dwarf Galaxy (European Southern Observatory)

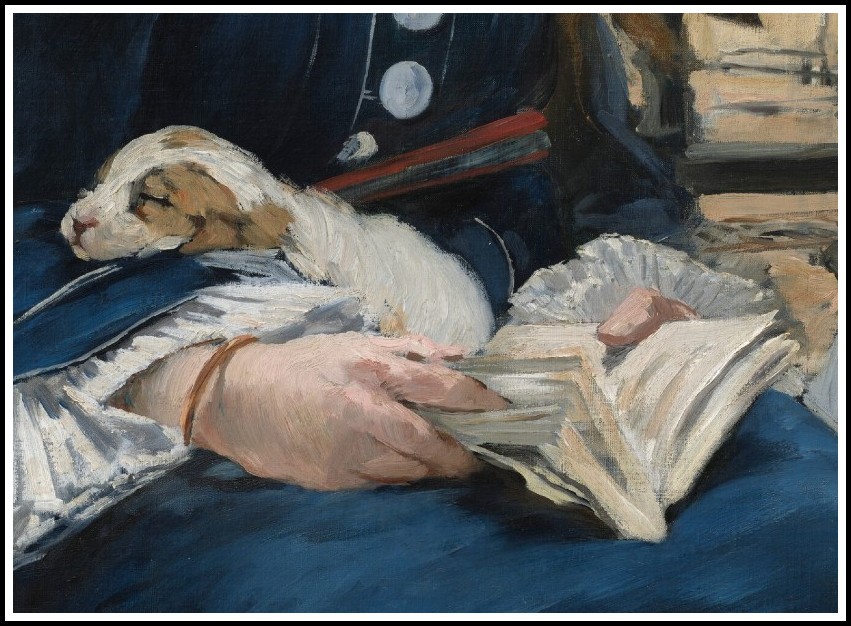

If Manet had wished to chart the extremes of animal consciousness, he ignored nothing. By placing the sleeping puppy in immediate proximity to the book, he fashioned a grand ligature between culture and biology, between experience and its sublimation in artifacts, of which painting is a special example. This is the true afternoon of dozing animals, of all animals including those who, like the child, graze. The states of human and animal consciousness have been enumerated. It should be noted that the general term ‘fauna’ in English, for animal life, is homonymic with the French word faune, for a particular animal. Manet has rendered a naturalist’s factual account of the ‘fauna’ one might encounter while wandering the precincts of a great city. The differing interdependencies of this ‘ecological niche’ identify a small corner of the closely observed modern world. The subject was arranged to render a densely focused meaning—but, then again, in art nature always conveys an unnatural, anthropocentric meaning.

Manet, The Gare Saint-Lazare, 1873 (detail)

If ‘nature’ is a cultural artifact, how much more artifice was required to reflect back on art itself? A reprise, The Gare Saint-Lazare also summarized certain of Manet’s past concerns. This sleeping puppy’s artistic pedigree descends from the slumbering lapdog that curls at the feet of Titian’s The Venus of Urbino, 1538.

Tiziano Vecellio, Venere di Urbino, 1538

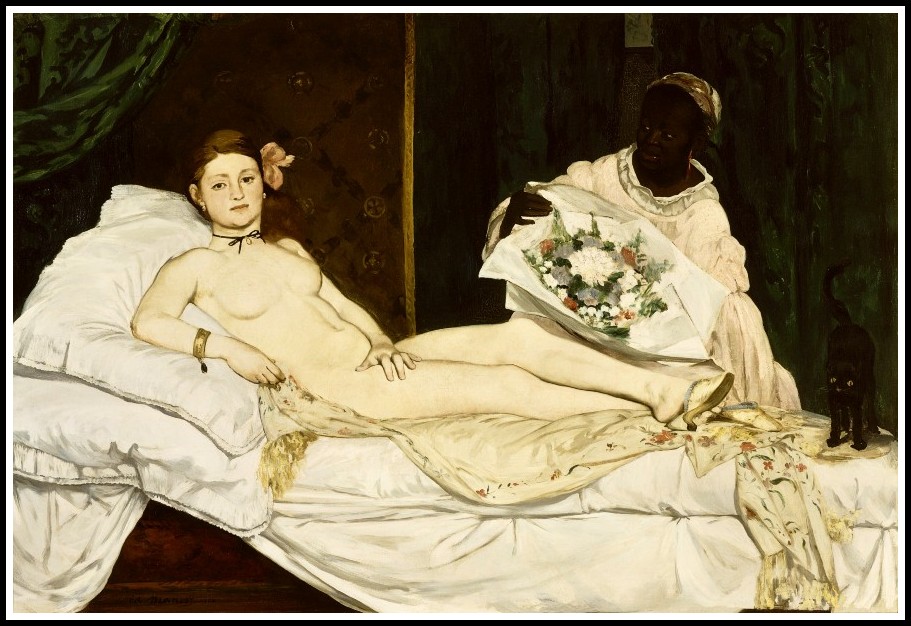

The Venus had served as the model for Manet’s Olympia, 1863, but in that work Manet had substituted a black cat for the faithful dog. When Titian painted the charming goddess identified with love, she was more chaste than the strumpet whose open lasciviousness affronted nineteenth-century Paris. For his insolent treatment of the Parisians’ open sexual traffic, the black cat served Manet’s purposes in the Olympia. Reinstated in The Gare Saint-Lazare, the brown-and-white parti-colored dog rests in his mistress’ lap, a surrogate for, or displacement of, the pubis.

Manet, Olympia, 1863

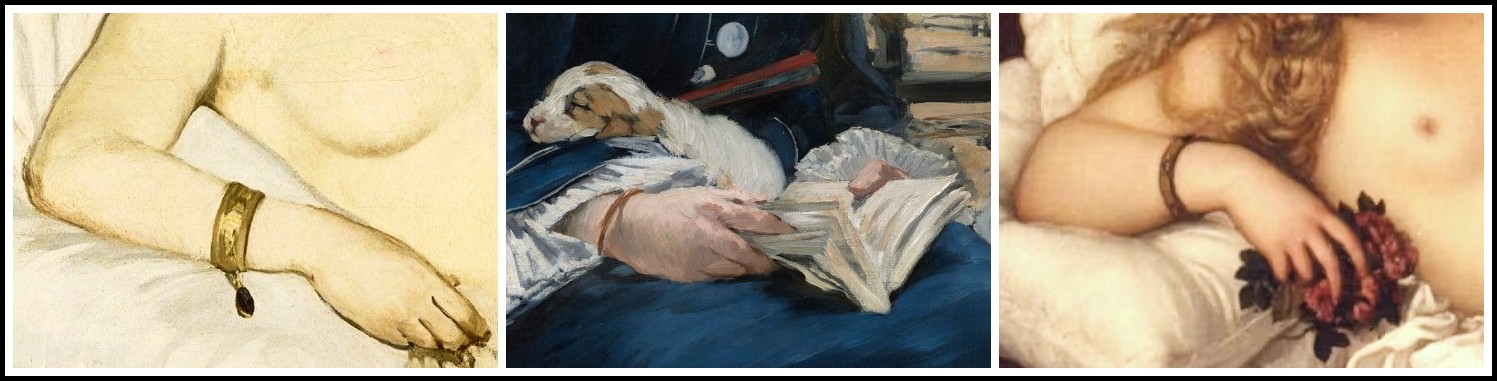

While no apparent sign of lust unites the puppy with references back through the Olympia to the Venus of Urbino, the painting’s lineage is nonetheless direct. In The Gare Saint-Lazare other details are held in common. The bangle worn on the right wrist by Titian’s Venus and by the Olympia appears once again on Victorine Meurent’s wrist in The Gare Saint-Lazare.

Manet, Olympia, 1863 (detail) | Manet, Gare Saint-Lazare, 1873 (detail) | Titian, Venus d’Urbino, 1538 (detail)

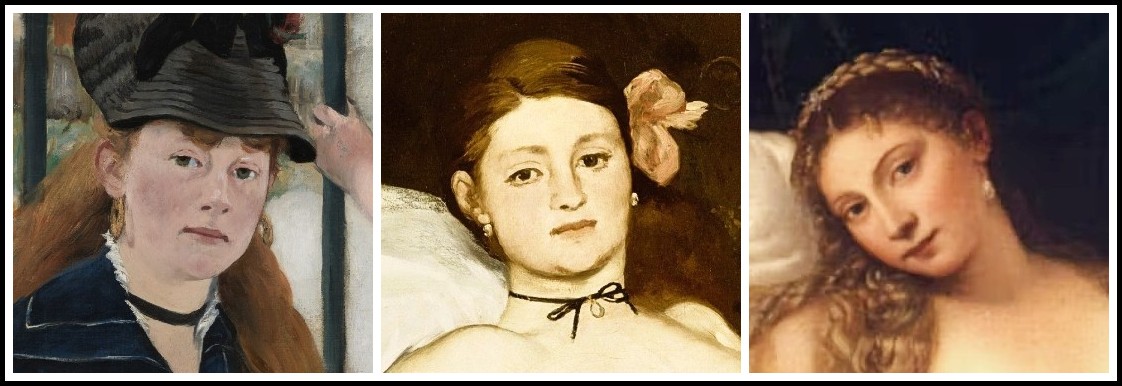

The thin black choker Mlle Meurent wore as Olympia is also worn at the Gare Saint-Lazare. Venus’s pearl earrings appear again in the Olympia, but they are replaced by gold ones in The Gare Saint-Lazare. A quietly repeated motif, this distinctive jewelry contributes an ornamental unity that underlies Manet’s portraits of Victorine Meurent. Aside from how she is clothed, the most basic difference between Mlle Meurent’s situation in The Gare Saint-Lazare and her role in other works is the model’s seated, frontal pose. This confrontational deportment arrives in Manet’s work from the storehouse of art history.

Manet, Gare Saint-Lazare, 1873 (detail) | Manet, Olympia, 1863 (detail) | Titian, Venus d’Urbino, 1538 (detail)

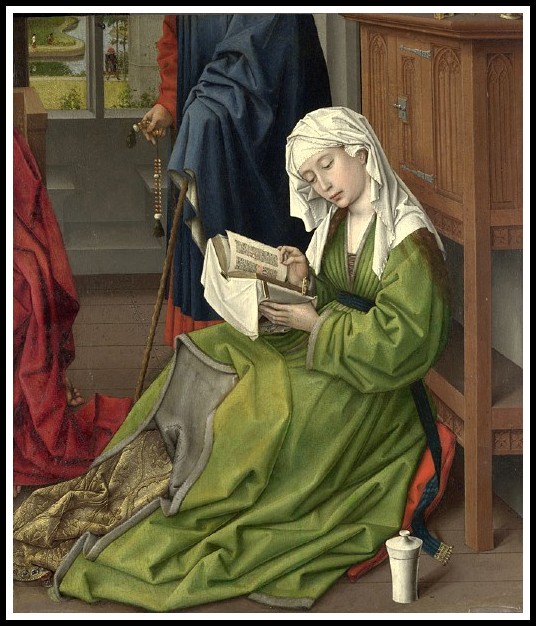

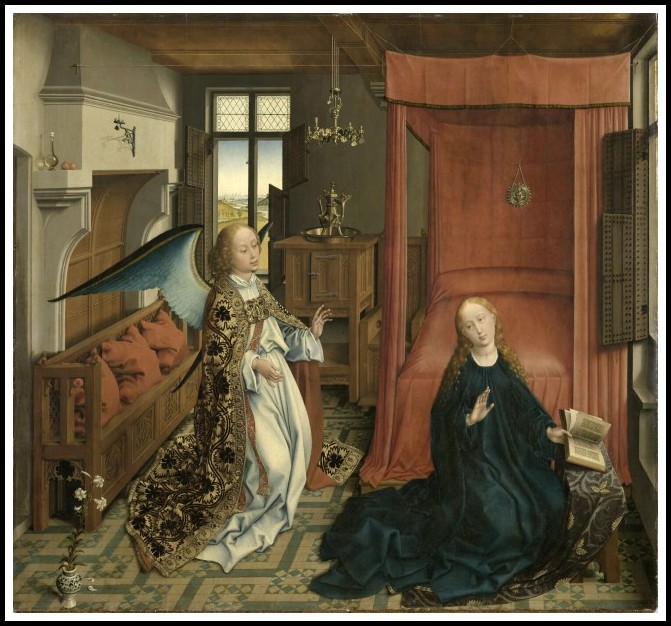

One source configures the pose, the upturned gaze, the reading, and the garb of a blue-clad figure: the ‘Virgin of humility.’ The motif, visible to Manet in myriad examples throughout Europe, is suggested by the blue color of what Victorine Meurent wears and by how she sits: upon the ground, reading. The Virgin epitomized the theme of humility when she sat plainly on the earth, without her throne.

Rogier van der Weyden, The Magdalen Reading, 1435

Blue: Mary; green: Magdalen

Characteristically, the Virgin sits reading within her chamber at the moment of the Annunciation, as in the central panel of Rogier van der Weyden’s dispersed triptych (Louvre, Paris). In such works the Virgin’s reading is interrupted by the archangel Gabriel, who, coming upon the woman unawares, startles her.

Rogier van der Weyden, The Annunciation, c. 1450

In one other situation, that of ‘Christ Appearing to His Mother’, the Virgin is suddenly and unexpectedly roused from her reading, an occupation in which she is often engaged as the model of piety. In this pose and occupation (reading), in her garb (blue dress and covered head), and in the action of her crucially interrupted reading, we recognize the Virgin of the Annunciation (or the Virgin when Christ appears to her). Since Victorine Meurent is lacking only a halo, how are we to differentiate her from her evident source? We are, after all, dealing with an artist whose concerns, attested in several paintings, were not wholly secular. Manet painted religious scenes out of an authentic need and from a Christianity against whose church he is not recorded as having made anti-Catholic pronouncements. His Catholicism, inherited as part of the national culture and his haute-bourgeois upbringing, was practiced, if at all, with grandly deliberate Parisian consciousness.

Rogier van der Weyden, Christ Appearing to the Virgin, c. 1440

Once the associations of Victorine Meurent’s pose and its implications for The Gare Saint-Lazare have been recognized, the figure assumes its place at the end of a chain of overtly religious citations—finally, another adaptation. In the past, Manet had dressed Victorine as The Street Singer, c. 1862…

Manet, Street Singer, 1862

… and as a transvestite for Mlle V… in the Costume of an Espada, 1862; the next year he undressed her for the Olympia. Now, a decade later, he could borrow the blue dress and pose of a seated Virgin. Although it may be considered a strange concept, it is really no odder to find this modern Parisian as a Holy Virgin than to find many of the other adaptations/transformations that Manet worked into his art.

Manet, Mademoiselle V… in the Costume of an Espada, 1862

Accordingly, three observers occupy the apex of the painting’s visual cone, the spot at which Victorine Meurent stares. The artist, at whom the model gazes (as he works), resides (simultaneously and coextensively) with us, and he and we are integrated at the vantage from which we view the picture. Also, the spectator who peruses the painting meets the eyes of the seated woman, as the archangel Gabriel when he startled the seated Virgin. The Gare Saint-Lazare’s spectator assumes the role and position of the angel Gabriel, and we are stand-ins for Manet. This compression of the tripartite spectator—not the first in art history—occurs at the point in space at which Victorine Meurent focuses.

The Tripartite Spectator of Manet’s The Gare Saint-Lazare

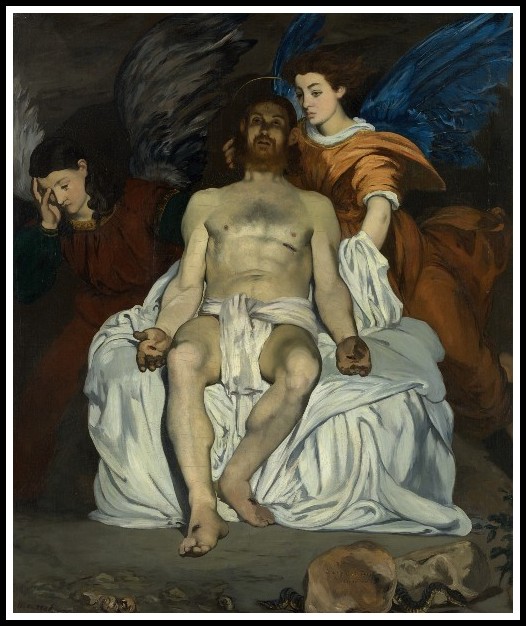

Recalling the occasion when the Virgin was thus seated, the artist could have imagined himself as the wounded Christ. His sufferings caused by the Olympia may have turned his mind to archetypal suffering, which prompted him to produce the Christ with Angels, 1864, the year after the Olympia, and now a new sort of synthesis brought religion to mind once more. If Manet discovered Victorine Meurent’s pose in the form of the seated Virgin and then compounded this image with references to both his own Olympia and its other intrinsic sources, we discover an especially complex network of signals to the art of the past. This sophisticated painter, who had gleaned the past for esoteric references to sustain the composition of the Déjeuner sur l’herbe, would have been precisely the sort to combine such variously gathered material again.

Manet, The Dead Christ with Angels, 1964

IX. THE CRUCIAL MISUNDERSTANDING

Albert Aurier, 1892: The nineteenth century—which in its childish enthusiasm has for eighty years vaunted the omnipotence of scientific observation and deduction, declaring that there is no mystery which does not yield to its lenses and scalpels—seems at last to becoming aware of the absurdity of its boasts and the emptiness of its efforts. Man is still surrounded by the same mysteries, the same formidable, enigmatic unknown, which had only become darker and more terrifying since it has been the fashion to ignore it. For some years past it has been clear to even the most casual observer that intellectual and artistic development in France is subject to two conflicting currents. The Gare Saint-Lazare’s components are not individually esoteric, but the manner of their organization, Manet’s way of thinking, is ‘difficult,’ much as modern poetry (starting with Mallarmé) seems ‘difficult’ and obscure. From commonplace materials Manet, too, arrived at such obscurity; he inquired into the very manner of our comprehension. For if The Gare Saint-Lazare is ‘about’ anything, it concerns our awareness and our manner of apprehending the world. These topics appear as unexpected implications. Such corollaries suggest that Manet’s contemporaries’ acceptance or rejection of the painting may have arisen from the treatment he afforded his subjects.

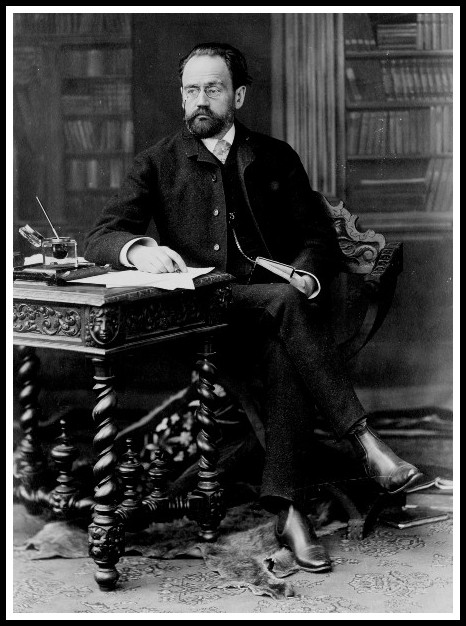

External Reality | Manet, The Gare Saint-Lazare, 1873: The ‘Magic Synthesis’ | Internal Reality

As noted earlier, the work was first treated with an obloquy that does not reveal how this seemingly ordinary subject could engender such critical vilification. Yet modern writers, too, have noted the opacity of Manet’s subject. For example, Mauner remarks that it is clear that what we know least about in Manet’s art is his content, to what extent it resides in his pure painting and to what extent it is to be found in his overt subject matter. The principal objections to viewing Manet’s art as consisting of legible entireties (at least for those paintings of the period starting with The Gare Saint-Lazare) issues not from anything Manet himself said or wrote but from a supporter, who was, paradoxically, one of the major voices of his day: Émile Zola. The great naturalist writer ‘excused’ Manet from literary engagement, even while certifying the artist’s intimacy with current writers. Zola deformed Manet’s intentions to correspond more closely to his own naturalist bent and goals. Manet, reticent if not supremely self-reliant, never objected but simply continued to paint as his needs dictated. Also, Manet’s career and reputation were not so well established that he could risk estranging Zola’s enthusiastic support in order to cavil over minor points when his entire artistic enterprise was under attack.

Nadar, Emile Zola, BnF

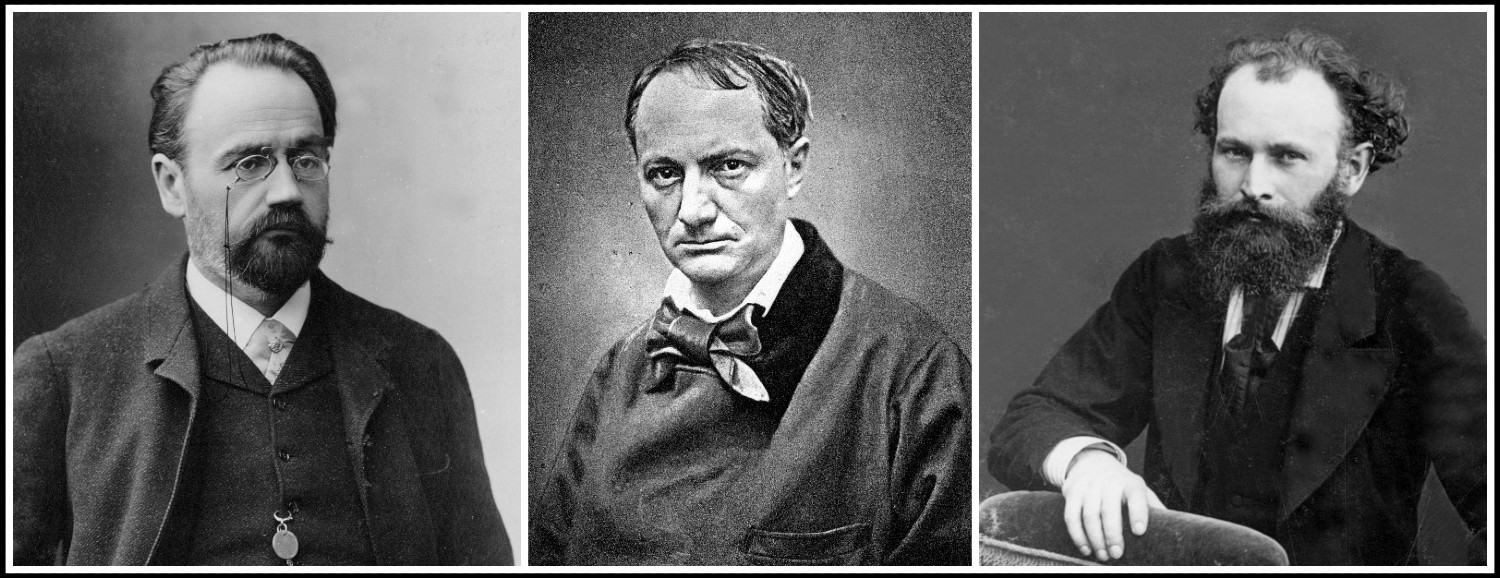

In a striking passage, Zola championed Manet’s art, but in terms that deflected subsequent investigation: I will use this opportunity to protest against the relationship that has been asserted between the paintings of Édouard Manet and the poems of Charles Baudelaire. I know that a lively sympathy has brought the poet and the painter together, but I think I can affirm the latter has never made the blunder, committed by so many others, of wanting to put ideas in his painting. The brief analysis I have given of his talent proves with what naïveté he places himself before nature. He is guided in his choice only by the desire to obtain beautiful color areas, beautiful oppositions. It is silly to try to make a mystical dreamer out of an artist obedient to such a temperament. The consequences of such a statement, and of many similar statements, decisively influenced subsequent viewers. In this text was born the image of Manet as the ‘painting animal,’ the bland unthinking naturalist, a realist painter who advanced Zola’s stance. Zola’s position mandated, and to some degree dictated, that successive spectators observe Manet’s art in terms of Baudelaire’s massively important criticism while discounting any fundamental artistic harmony, contemporaneity, or shared sensibilities between Manet and Baudelaire.

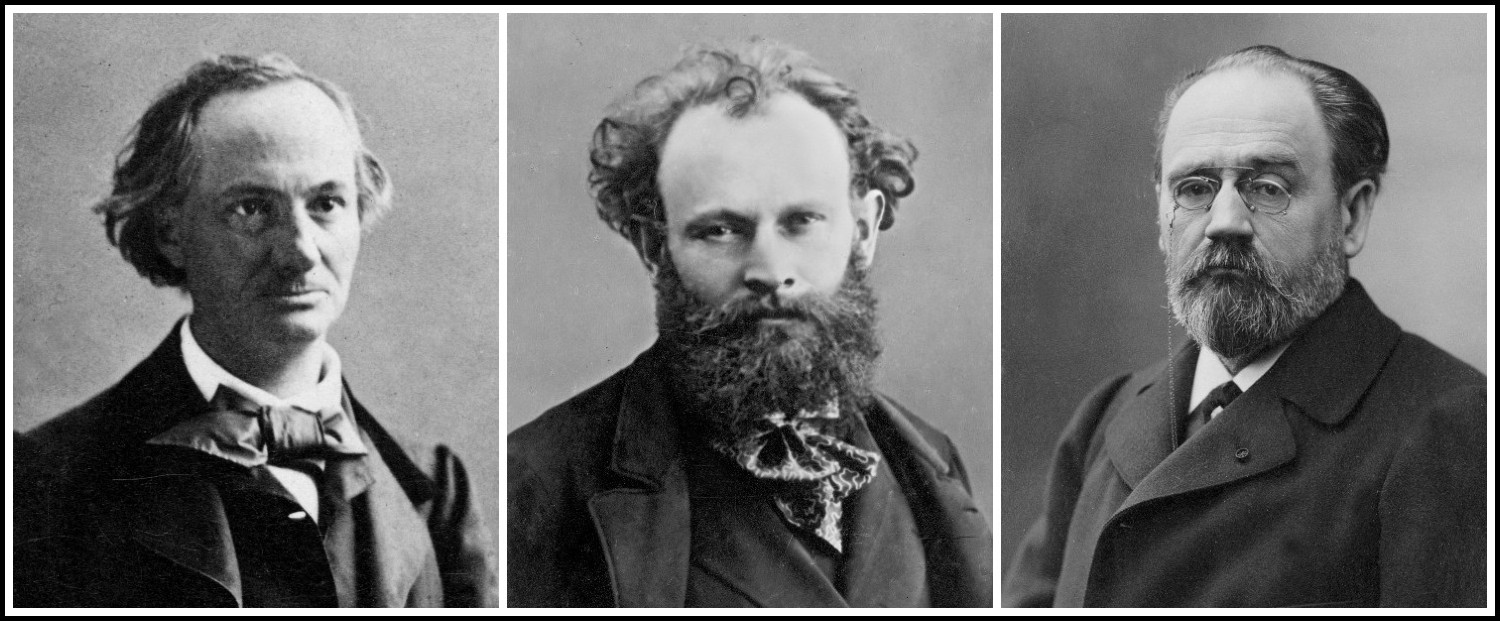

Emile Zola | Charles Baudelaire | Edouard Manet (BnF)

That Manet was the archetypal painter of his time was never in doubt for Zola or for the many readers who followed his proposal. Simultaneously, Baudelaire very much set the tone of writing for a certain, increasingly important sector of the world of letters. That Manet and Baudelaire might have been engaged in similar programs never really entered the question, and Zola dismissed the possibility, although it has long been clear that Manet’s art is far from a simple exposition of any obvious propositions. Thus, following the tone first set by Zola, for subsequent chroniclers Baudelaire seemed to remain an ardent and hardly disinterested, although somehow disengaged observer, who had made a direct contribution to Manet’s art only through his critical writing. Baudelaire’s personality and his presence in the life of Manet was severed from Baudelaire’s thinking and writing. That Zola may have contributed to the bifurcation of these two streams is highly probable. On one hand, the criticism fostered by Baudelaire eventually carried the day and has posited the basic terms by which we view Manet’s art. On the other hand, the subject matter of Manet’s art and his approach to art itself have not been successfully aligned with Baudelaire’s own position.

Charles Baudelaire | Edouard Manet | Emile Zola (BnF)

RELATED POST IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2024 | All rights reserved

Comments