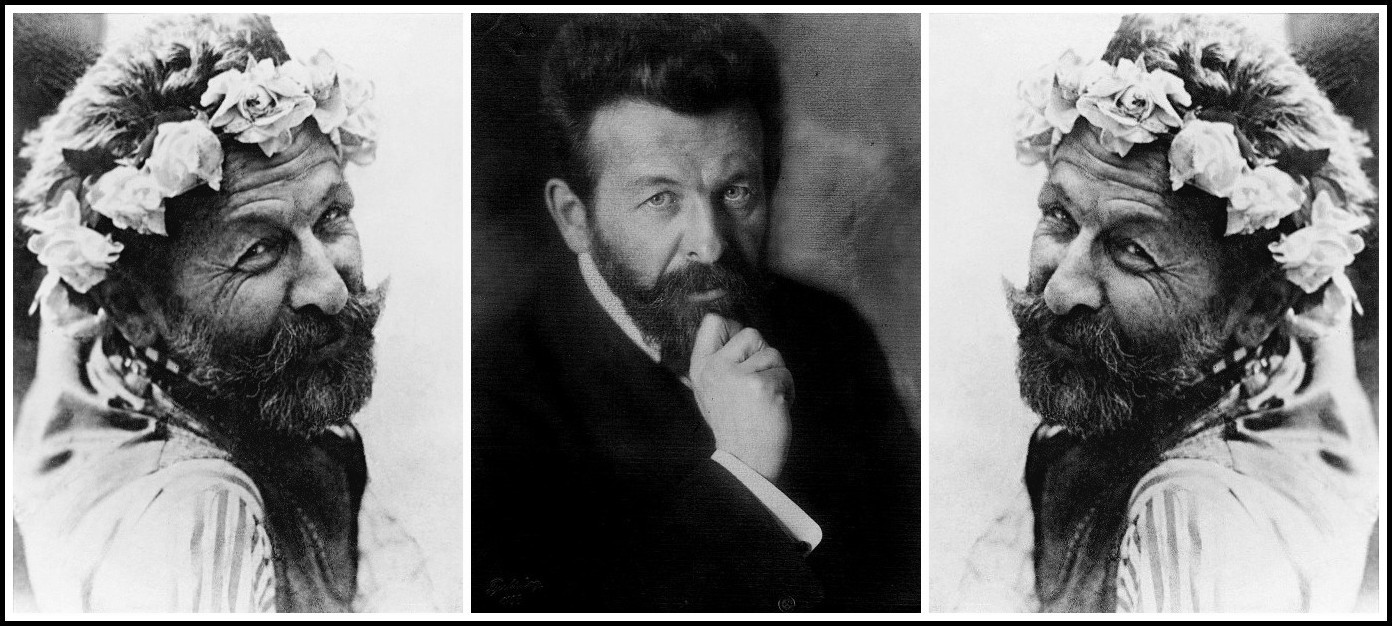

Ludwig Pfau, Richard Dehmel, Stefan George

SCHOENBERG LIEDER: THE COMPOSER AND GERMAN POETRY

Robert Vilain

Posted by kind permission of Robert Vilain, Honorary Professor of German & Comparative Literature, University of Bristol, and Senior Tutor, St Hugh’s College, University of Oxford

Abbreviated from Robert Vilain, ‘Schoenberg and German Poetry’ in Schoenberg and Words: The Modernist Years, ed. Charlotte Cross & Russell Berman (NY: Garland Publishing, 2000) pp. 1-29

Arnold Schoenberg: Queen of Hearts, 1909 | Green Self-Portrait, 1910

I. INTRODUCTION

The present essay is an attempt to approach from the perspective of the literary scholar the question of Schoenberg’s relationship with the poetry of his contemporaries, looking in particular at what have been considered inconsistencies in his literary taste and at some of the elements that attracted him to particular poets. This will involve an examination of these poets in relation to each other as well as in relation to Schoenberg, and some assessment of their literary-historical context. I shall not attempt to analyze what Schoenberg as a composer made musically of the texts he chose, but will try to draw out some of the qualities that may have stimulated him as a reader, suggesting that his discretion and sensitivity in this respect are greater than is sometimes acknowledged. I shall suggest that there is a degree of unity in the criteria that Schoenberg adopted, consciously or unconsciously, in his selection from literary texts, and that these criteria are both stylistic and thematic. Between 1893 and 1916, Schoenberg was moved to set poems by some sixty different authors—poets whose names are nowadays almost completely unknown, such as Oskar von Redwitz, Ottokar Kemstock, and Wilhelm von Scholz, and better-known writers as disparate as Petrarch and Rainer Maria Rilke, Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Rabindranath Tagore, Nikolaus Lenau and Richard Dehmel, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Jens Peter Jacobsen, Gottfried Keller and Stefan George. Statistically, Ludwig Pfau, Richard Dehmel, and Stefan George emerge as the most significant, with fourteen, seventeen, and twenty texts respectively, and it is on these poets that I shall focus this essay.

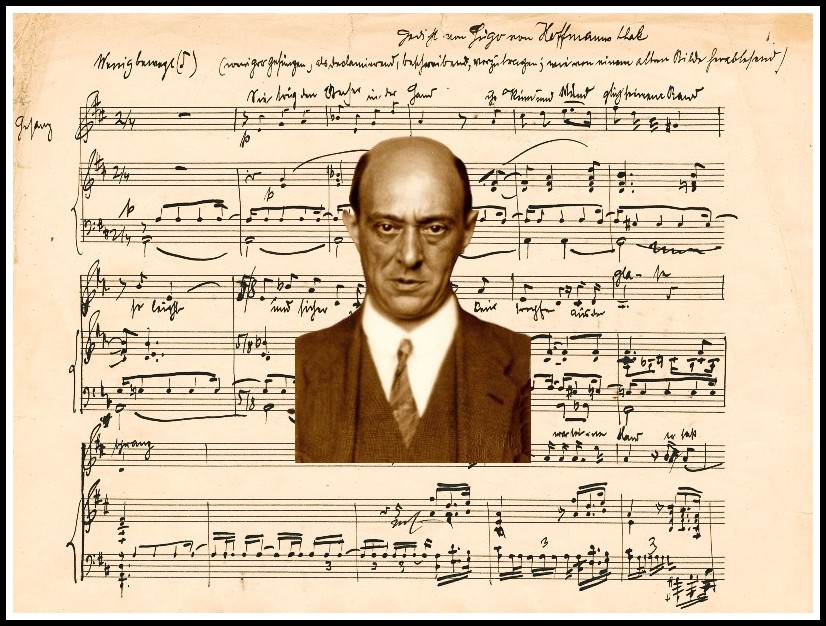

Arnold Schönberg, Die Beiden, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, 1899 | Arnold Schoenberg, Prague 1924

II. LUDWIG PFAU

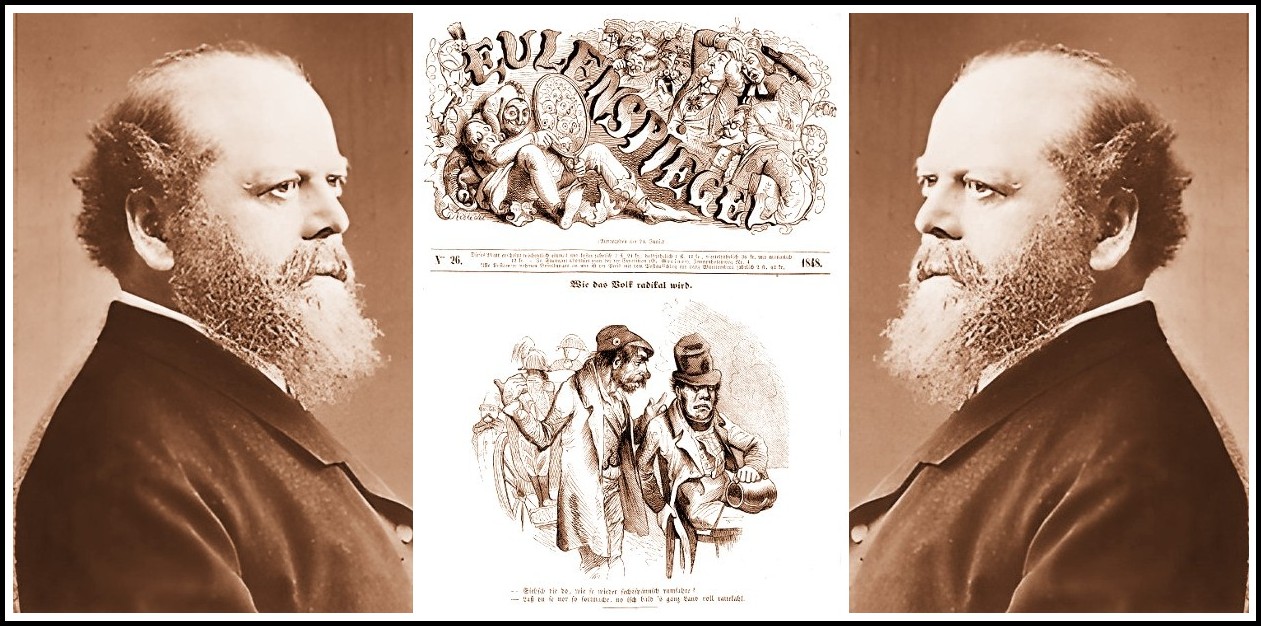

Walter Bailey suggests that ‘in the tradition of Brahms and Strauss, Schoenberg’s choice of poetry was not at first guided by literary worth’ and implicates in this judgment Ludwig Pfau, the poet set most frequently before 1897. Karl Ludwig Pfau (1821-1894), one of the 1848 revolutionaries, was convicted of high treason and spent many years in exile in Switzerland and France before returning to Germany in 1863. Pfau was not only a poet; indeed, he was for a while best known for his journalism, editing the satirical magazine Eulenspiegel (named after the fourteenth-century practical joker, whose simple comic exploits passed into German popular tradition).

Ludwig Pfau, Eulenspiegel N° 26, 1848

The poems by Pfau set by Schoenberg between 1894 and 1897 are unremarkable in form and subject matter. His love lyrics have a touch of anxiety about them, and several concern rejection or loss. In ‘Einsam bin ich und alleine’, the first and fourth lines recur as a refrain, heightening the poignancy of the situation.

LUDWIG PFAU 1: EINSAM BIN ICH UND ALLEINE (1895) | LONELY AM I AND ALONE (tr. R.J.)

Einsam bin ich und alleine,

Tragen muß ich Leid und Schmerz,

Und zurück in’s eigne Herz

Rinnt die Träne die ich weine.

Frühling kam und hat nicht eine

Rose mir gesteckt an’s Herz;

Frühling kam mit Spiel und Scherz,

Einsam bin ich und alleine.

Große Augen, arme Kleine,

Schick’ ich suchen allerwärts;

Aber in kein fremdes Herz

Rinnt die Träne die ich weine.

Lonely am I and alone,

Sorrow and heartache I must bear;

Back into my own heart, alas,

Run the tears that I cry.

Spring came and lay no rose

Upon my heavy heart;

Spring came with games and laughter,

Lonely am I and alone.

Big eyes, little one alone,

I send them searching everywhere;

Into no other heart, alas,

Flow the tears that I cry.

Schoenberg set a mixture of the melancholy and the jolly. ‘Gott grüß dich, Marie!’ [Greetings, Marie!] is a dancing song about a pretty girl, and again there is a refrain, this time three lines of rhythmical nonsense: ‘Heissarumbidibum / Mit der kieinen Killekeia / Mit der großen Kumkum’.

LUDWIG PFAU 2: GOTT GRÜß DICH, MARIE! (1895) | GREETINGS, MARIE! (tr. R.J.)

Gott grüß dich, Marie!

Komm’, die Spielleut’ sein hie,

Tun die Geiglein kuranzen,

Die Seiten ausfranzen.

Heissarumbumdibum!

Mit der kleinen Kilikeia,

Mit der großen Kumkum.

Gelt! Schatz? Ich und du!

Hast ein neues Paar Schuh,

Hast ein funkelrots Mieder,

Hüpft auf und hüpft nieder.

Heissarumbumdibum!

Mit der kleinen Kilikeia,

Mit der großen Kumkum.

Ein Kuß und ein Schmatz!

Ei du herziger Schatz!

Über Stauden und Stöcklein

Laß fliegen dein Röcklein.

Heissarumbumdibum!

Mit der kleinen Kilikeia,

Mit der großen Kumkum.

Wart! unten beim Grab’n

Liegt ein Spielmann begrab’n,

Und da stolpern wir Schwäblein

Und fallen in’s Gräblein.

Heissarumbumdibum!

Mit der kleinen Kilikeia,

Mit der großen Kumkum.

Greetings, Marie!

Come, the minstels are here,

The violins are swaying,

The pages are fraying.

Heissarumbumdibum!

With the little Kilikeia,

With the big Kumkum.

Right! Darling? Me and you!

Got a new pair of shoes,

Got a sparkling red bodice,

Hop up and hop down.

Heissarumbumdibum!

With the little Kilikeia,

With the big Kumkum.

A kiss and a smack!

Oh you sweet darling!

Over rustling straw and sticks

Let your little skirt fly.

Heissarumbumdibum!

With the little Kilikeia,

With the big Kumkum.

Wait! Down by the grave

A minstel lies buried,

And that’s where we Swabians stumble

And fall into the grave.

Heissarumbumdibum!

With the little Kilikeia,

With the big Kumkum.

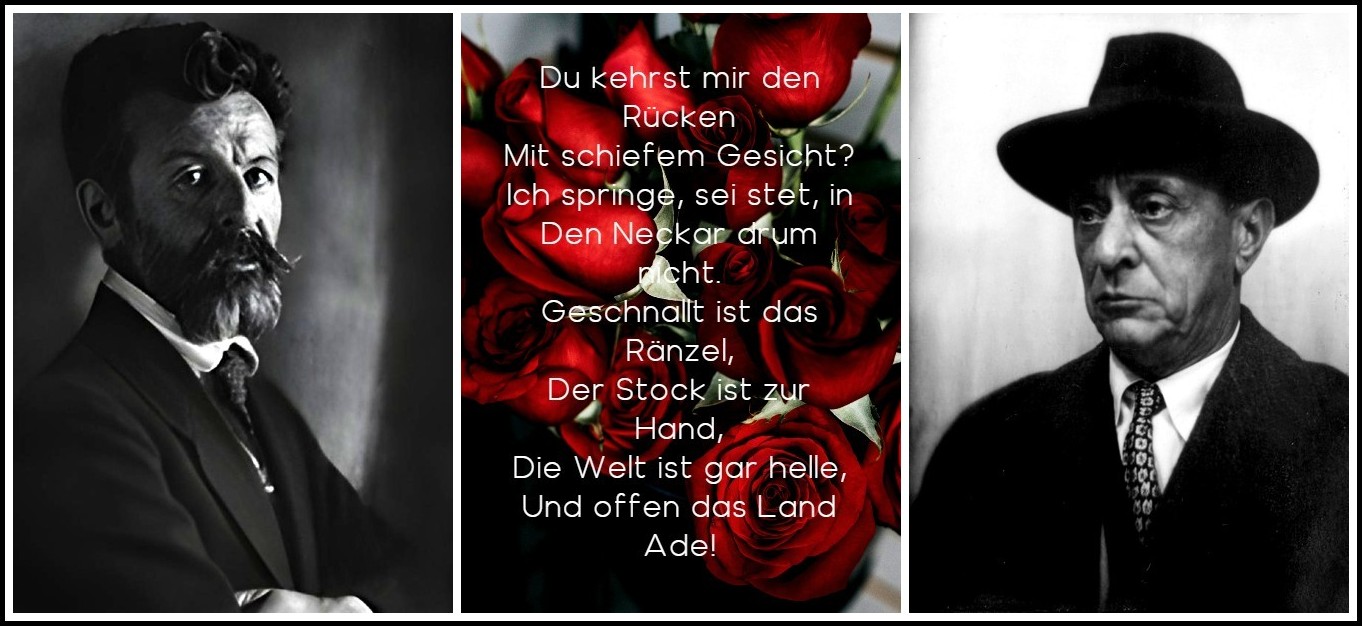

The rejected lover in ‘Du kehrst mir den Rücken’ [Are you turning your back on me?] shrugs his shoulders at the girl who rejects him and bouncily saunters into the big wide world to look for another. Furthermore, apart from the monosyllabic exclamations that end each stanza, the whole poem is in amphibrachs: the amphibrach consists of a stressed syllable sandwiched between two unstressed syllables, so in sequence they produce a jaunty, almost jigging rhythm. Schoenberg seems therefore to have been attracted to Pfau for his clarity and simplicity. Pfau was no poetic radical, but all the poems Schoenberg chose convey plain emotional states efficiently, if sometimes rather blandly. What they would represent for a late-nineteenth-century composer is perhaps a model of technical facility, a poet perfectly at home with the standard stylistic and rhythmic repertoire of the past fifty or sixty years.

LUDWIG PFAU 3: DU KEHRST MIR DEN RÜCKEN (1895) | ARE YOU TURNING YOUR BACK ON ME? (tr. R.J.)

Du kehrst mir den Rücken

Mit schiefem Gesicht?

Ich springe, sei stet, in

Den Neckar drum nicht.

Geschnallt ist das Ränzel,

Der Stock ist zur Hand,

Die Welt ist gar helle,

Und offen das Land

Ade!

Es glühn wohl viel Sterne

Am himmlischen Zelt,

Es ziehn wohl viel Straßen

An’s Ende der Welt;

An jeglicher Straße

Steht mannig ein Haus,

Schaut immer ein freundliches

Paar Augen heraus

Ade!

With a smirk on your face

Are you turning your back on me?

Not for that will I jump

Into the nearest river.

The knapsack is strapped on,

The hiking stick’s at hand,

The bright world awaits,

Wide-open is the land.

Farewell!

With a riot of stars

The firmament is aglow;

To the ends of the earth

Many a road leads.

And on every street

Many a house stands,

A pair of friendly eyes

Always looking out.

Farewell!

III. RICHARD DEHMEL

Richard Dehmel is quite a different case from Ludwig Pfau. He occupies a curious position in German literary history, himself embodying something of the complex and self-contradictory eclecticism with which Schoenberg has been charged. Walter Frisch remarks of the shift from Pfau and his ilk to Dehmel that ‘the quality of the poetry seems directly related to the musical results,’ yet it was and is by no means universally acknowledged that Dehmel’s effusions represent poetry of a particularly high quality. He has all but disappeared from the university syllabus, for example, and there is virtually no critical interest in his work nowadays. Apart from Schoenberg, his poems inspired and were set by Richard Strauss, Alexander von Zemlinsky, Hans Pfitzner, Max Reger, and Anton Webern.

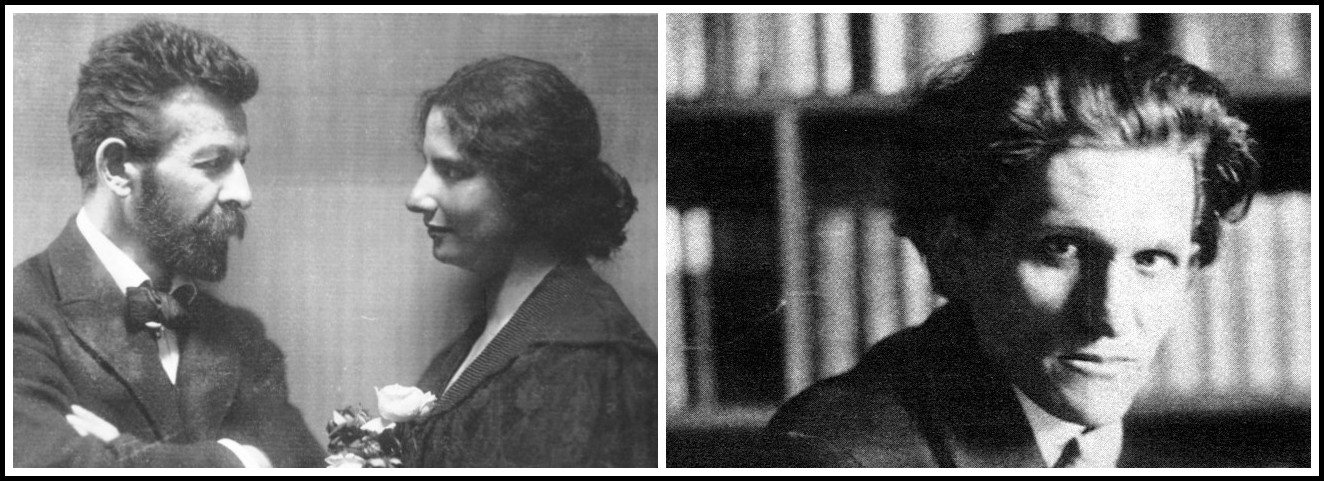

Richard Dehmel, 1910 & 1908 (Middle photo: Rudolph Dührkoop)

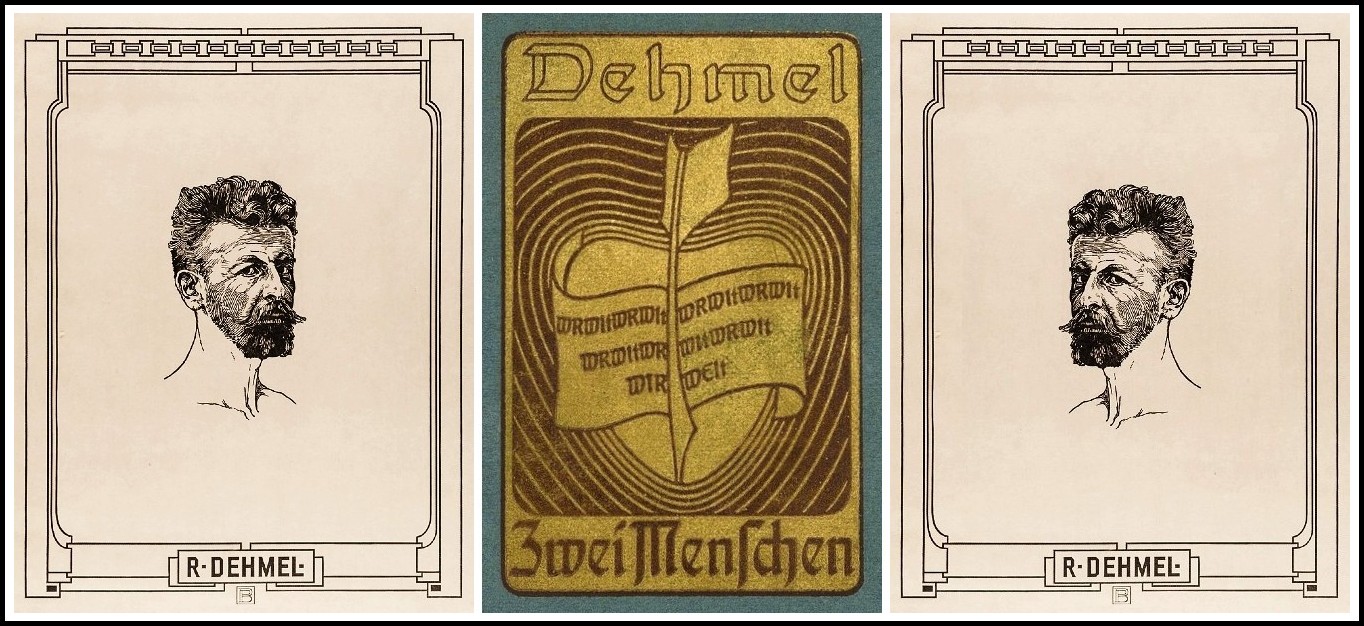

The quasi-religious tone of much of Dehmel’s work indicates affinities with the Jugendstil style of the late nineteenth century. He often asked well-known Jugendstil artists to illustrate his publications: the front cover of the second, revised edition of Erlösungen [Redemptions] (1898), is by E. R. Weiss; the typeface for the first edition of Zwei Menschen [Two People], the collection that grew out of the poem ‘Verklärte Nacht’ [Night Transfigured], originally in the collection entitled Weib und Welt [Woman and World], is by Peter Behrens.

Peter Behrens: Woodcut print of Richard Dehmel | Cover for Dehmel’s Zwei Menschen

The white swan in ‘Landung’ [Landing] and the black swan in ‘Der Richer’ (The Avenger], from his first collection, Erlösungen: Eine Seelenwanderung in Gedichten [Redemptions: A Soul’s Journey in Poems] (1891), are part of the iconography of Jugendstil, too. Beyond this, Dehmel’s whole artistic program had much in common with the Jugendstil aim of transfiguring reality via art, vitalizing the outside world through the intensity of inner experience.

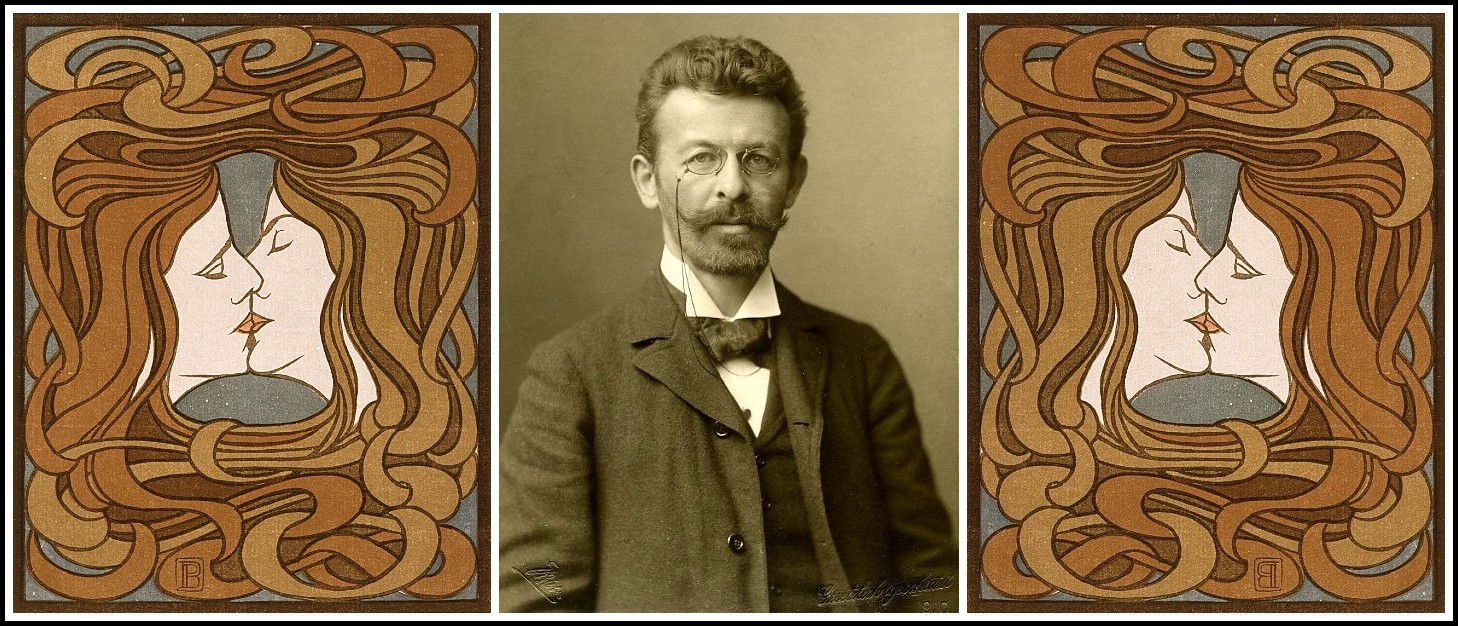

Peter Behrens, The Kiss, 1898 | Richard Dehmel, 1910 (Photo: Emil Bieber)

Dehmel’s second collection, Aber die Liebe [But Love] (1893), develops a Nietzschean/Christian duality (an odd but powerful pairing that was to resurface again and again in expressionist literature) allowing it to crystallize around the dominant theme of love. On the one hand, he shows how the modern age’s hunger for individuality leads to isolation and alienation, but on the other he repeatedly returns to an affirmation of the healing power of love. Stylistically there is still some of the passionate rhetoric of Erlösungen, but there is also the distanced, observing manner of the impressionist. Schoenberg’s letters to Dehmel, written more than fifteen years after he set his first Dehmel texts, explain the significance of the poetry and the way in which it affected him: Your poems have had a decisive influence on my musical development. It was because of them that I was for the first time compelled to seek a new tone in lyric writing. That is, I found it without having to look, by reflecting in music what your poems stirred up in me. He expands on this in a letter written on the occasion of Dehmel’s fiftieth birthday, 18 November 1913: I have already said that a Dehmel poem marks almost every turning-point of my musical development, and that it was nearly always in responding to your tones that I found the new tone that was to be my own. This tone was conveyed to us by the content, which was difficult to understand at that time, but more importantly by the sound of your poetry, which we absorbed fully. I have always responded to you with my ‘sound-understanding’ [Klang-Verstand] and because of this have perhaps quickly been able to penetrate the ‘sense of the senses’ [Sinnen-Sinn].

Richard Dehmel | ‘Du kehrst mir den Rücken’ | Arnold Schoenberg

RICHARD DEHMEL 1: NICHT DOCH! (1897) | COME NOW! (tr. R.J.)

Mädel, laß das Stricken — geh,

thu den Strumpf bei Seite heute;

das ist was für alte Leute,

für die Jungen blüht der Klee!

Laß, mein Kind,

komm, mein Schätzchen;

siehst du nicht, der Abendwind

schäkert mit den Weidenkätzchen

Mädel, liebes, sieh doch nicht

immer so bei Seite heute;

das ist was für alte Leute,

junge seh’n sich ins Gesicht!

Komm, mein Kind,

sieh doch, Schätzchen:

über uns der Abendwind

schäkert mit den Weidenkätzchen

Siehst du, Mädel, war’s nicht nett

so an meiner Seite heute?

Das ist was für junge Leute,

alte gehn allein zu Bett!

Was denn, Kind?

weinen, Schätzchen?

Nicht doch — sieh der Abendwind

schäkert mit den Weidenkätzchen

Girl, no more knitting, enough!

Cast aside that stocking today;

That’s a pastime for the old and grey,

For the young the clover is blooming!

Leave it, my child,

Come, my darling;

Don’t you see the evening breeze

Is flirting with the pussy willows?

Girl, dear, turn not away

Your gaze again today;

That’s what the old and grey do,

The young stare into each other’s eyes!

Come, my child,

Little darling, look:

Above us the evening breeze

Is flirting with the pussy willows

You see, girl, wasn’t it nice,

Your body beside mine today?

That’s what the young do,

The old go to bed alone.

What is it, child?

Crying, little darling?

Come now – see the evening breeze

Flirting with the pussy willows

RICHARD DEHMEL 2: MÄDCHENFRÜHLING (1897) | GIRLS’ SPRING (tr. Robert Vilain)

Aprilwind;

alle Knospen sind

schon aufgesprossen;

es sprießt das Grund,

und

sein Mund

bleibt so verschlossen?

Maisonnenregen;

alle Blumen langen,

stille aufgegangen,

dem Licht entgegen,

dem lieben Licht.

Fühlt, fühlt er‘s nicht?

April wind;

all the buds have

already sprouted,

the ground is sprouting,

and

his mouth

remains closed?

May-sun-showers;

all the flowers,

having quietly opened out,

are stretching towards the light,

the lovely light.

Does he really not feel it?

The idiosyncrasies of this poem are perhaps best understood against the background of the more famous poem from Heine’s Buch der Lieder [Book of Songs] that opens Schumann’s Dichterliebe [Poet’s Love], op. 48:

Im wunderschönen Monat Mai,

Als alle Knospen sprangen,

Da ist in meinem Herzen

Die Liebe aufgegangen.

Im wunderschönen Monat Mai,

Als alle Vögel sangen,

Da hab’ ich ihr gestanden

Mein Sehnen und Verlangen.

In the glorious month of May,

when all the buds were bursting forth,

then love blossomed

in my heart.

In the glorious month of May,

When all the birds were singing,

then I confessed

my longing and desire to her.

Heinrich Heine | Oskar Zwintscher, Portrait with Yellow Daffodils, 1907 | Richard Dehmel

Dehmel’s poem uses much of the same vocabulary and imagery as Heine’s but tums it inside out almost like a glove. Where Heine uses the blossoming of the flowers in May both to mirror and to motivate the (male) speaker’s declaration of love, Dehmel’s speaker is a girl, conscious nearly to the point of bursting that spring growth is rampant in nature, yet frustrated and unable to see why her beloved is not responding like Heine’s young man. Five of Heine’s eight lines share a rhyme sound, two in the first stanza as part of a familiar rhyme scheme, and three in the second, deliberately breaking up that familiar pattern—which helps to communicate the speaker’s rising emotion. Dehmel similarly plays with formal expectations, but to the opposite effect. The first stanza almost fulfills a standard aabccb pattern, but the penultimate line is split into two, producing three c-rhymes, one from the monosyllabic fifth line, which slows down the pace and introduces the note of tension. The second stanza’s mirroring device (putting the couplet at the end to produce deedff) fails to ‘round off’ the emotional content of the poem as one might expect, partly because the last word is negative, partly because the rhyme is itself used to articulate the gap between the yearning flowers and the indifferent boy.

Frank Wedekind, Spring Awakening, Katrin Lindner | SchauspielKIEL, Kiel, 2016

Rhythmically, too, Dehmel does the opposite of Heine, who uses the regularity of the iambic meter to underline the fact that the first line of each stanza is longer than the last three, emphasizing the mounting emotion. Dehmel’s first lines are single evocative words, establishing no metrical expectation; lines two to four of stanza one and two to five of stanza two fall into something approaching regularity, the alternation of stressed and unstressed syllables to accompany the construction of the girl’s romantic dream-picture; twice, however, an interruption is used to convey her profound unsettlement as the fifth line of stanza one splits and the fifth of stanza two is cut short, and in both cases the last line begins with two stressed syllables, to mark the bursting of the bubble.

Frank Wedekind, Spring Awakening, Catharina May | Theaternatur, Benneckenstein, 2018

Frisch notes that ‘the remarkable harmonic planning and control in “Mädchenfrühling” are complemented by—actually, inextricably linked to—Schoenberg’s sophisticated treatment of meter and rhythm,’ and explains a series of metrical ambiguities in the setting. Nonetheless, his explanation of Schoenberg’s omission of Dehmel’s line eleven highlights what is in effect a creative misreading of the original: Schoenberg created an abbreviated ternary or ABA’ form, where the A’ section if so short that he ‘may well have felt it necessary to truncate the poetry of the B section (‘Maisonnenregen’} somewhat to achieve a rounded musical form that would not be grossly imbalanced’. The original poem is, however, not ternary in structure but what one might call ‘modified binary’: each stanza begins with an evocation of the season (first April, then May), moves on to the activity of nature (first the buds breaking open, then the flowers growing towards the sun), and finally registers the failure of the boy to act in parallel with nature. In the second stanza the middle section is longer or broken off less quickly, which suggests the pain of waiting and the girl’s growing frustration with the boy’s inability or unwillingness to respond to the increasingly obvious ‘clues’ that nature is providing. In Heine’s poem there is no chronological development; Dehmel provides one; Schoenberg’s setting seems to have imposed a third emotional structure on a familiar romantic topos.

Vikoria Hauer & Ludwig Weissenberger, Endlich Fruehlings Erwachen, Theater der Jugend, 2023

It is striking how often Dehmel’s love poems record problems, division, or dissatisfaction. Those of Weib und Welt, which caused such a scandal when they were published in 1896, are no exception, despite the fact that they emerged from Dehmel’s—ultimately fulfilled—emotions for Ida Auerbach. The first of the Dehmel settings of 1899, ‘Mannesbangen’ [Man’s Fear] is another such, even though it specifically evokes sexual fulfillment. The poem is a paradoxical conceit: the opening lines are almost defiant in self-defense, the central section then describes in sensual detail the very situation in which the speaker is most vulnerable, and it closes with an admission of fear and an accusation. But each element is double-edged: the woman running her hands through the man’s hair produces a sensation so acutely pleasurable that it becomes akin to pain; the accusation—’you sinner’—is not to be taken literally, but, given the position of the man’s head, should be read as an ironic declaration of complicity in sexual excitement; the trembling derives as much from sexual arousal as it does from fear—indeed, fear itself has only been evoked as an ironic way of expressing the true interpretation of the man’s trembling. The first two lines coolly fit themselves to the two clauses of the statement, but then the line lengths immediately begin to dislocate the statements, with a break after ‘deinen,’ and another after ‘solchen.’ The verb in the second of the subordinate clauses dependent on ‘wenn’ is delayed for four short, punchy lines by the comparison of hands with daggers, giving a sense of mounting tension released by the rhyme of ‘fahrst’ with ‘begehrst.’ Line 9, the longest in the poem, is also the most relaxed. After this release of tension, the last couplet reads more calmly than Frisch, for example, suggests. Nonetheless, the poem is acerbic to a degree not found in the earlier Dehmel collections, positing in its ironies an antagonism that keeps the partnership on edge, and there is nothing remotely folksy about it.

RICHARD DEHMEL 3: MANNESBANGEN (1899) | MAN’S FEAR (tr. Robert Vilain)

Du mußt nicht meinen

ich hätte Furch vor dir.

Nur wenn du mit deinen

scheuen Augen Glück begehrst

und mir mit solchen

zuckenden Händen

wie mit Dolchen

durch die Haare fährst,

und mein Kopf liegt an deinen Lenden:

dann, du Sündrin,

beb’ ich vor dir.

You must not think

I am afraid of you.

Only when you crave

happiness with your shy eyes

and run your

quivering hands

through my hair

like daggers,

and my head is lying on your loins:

then, you sinner,

I tremble before you.

It is related in style and mood to the overtly sadistic ‘Warnung’ [Warning] from the same collection.

RICHARD DEHMEL 4: FROM 6 LIEDER, OP. 3 – No. 3: WARNUNG | WARNING (tr. R.J.)

Mein Hund, du, hat dich bloß beknurrt,

und ich hab ihn vergiftet;

und ich hasse jeden Menschen

der Zwietracht stiftet.

Zwei blutrote Nelken

schick ich dir, mein Blut du,

an der einen eine Knospe;

den dreien sei gut, du,

bis ich komme.

Ich komme heute Nacht noch;

sei allein, sei allein, du!

Gestern, als ich ankam,

starrtest du mit Jemand

ins Abendrot hinein – Du:

denk an meinen Hund!

My dog, you, just growled at you,

And I poisoned him;

And I hate every human being

Who sows discord.

Two blood-red carnations

I send you, my blood you,

A bud on one of them;

Be good to the three of them, you,

Until I come.

I will come tonight;

Be alone, be alone, you!

Yesterday, when I arrived,

You were staring with someone

Into the setting sun – You:

Remember my dog!

Dehmel represents a significant advance for Schoenberg over Ludwig Pfau. There is a thematic development, since if both poets write of love, even Dehmel’s earlier lyric does so more subtly, combining positive and negative instead of switching between them. The poems from Weib und Welt that Schoenberg set are more complex still, straining emotions to their limits while both ironizing and refining them. The other advance is technical: Pfau’s verse was highly competent and produced some interesting effects, albeit little that could be called original; Dehmel’s writing—again even in the earlier, modified Volkslied style—responds technically to the complexities of the subject matter, manipulating rhythm in particular with a degree of freedom unknown to Pfau.

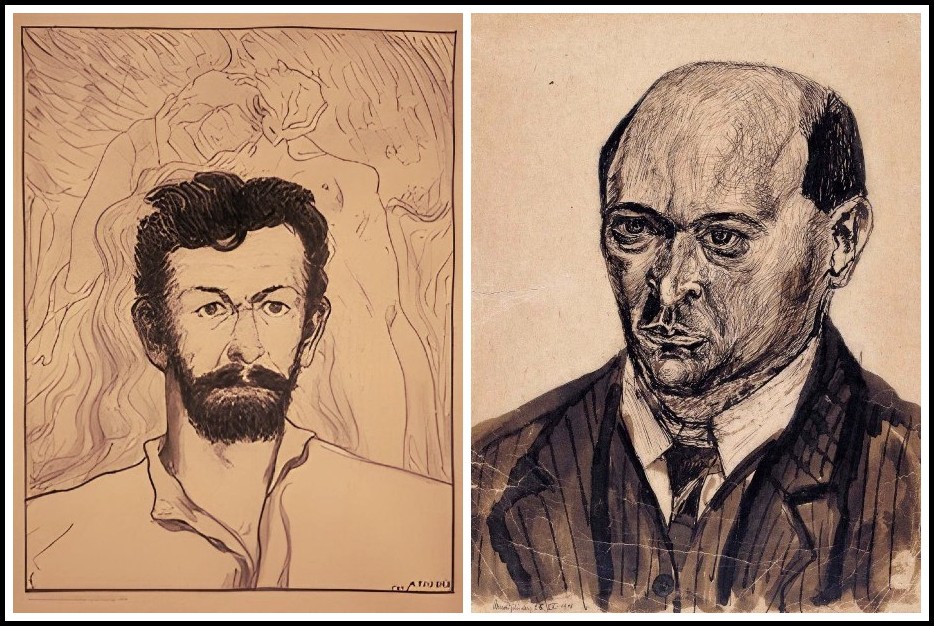

Emil Rudolf Weiss, Richard Dehmel, 1900 | Arnold Schoenberg, Self-Portrait, 1908

IV. STEFAN GEORGE

While Dehmel was abjuring the traditional influences that produced neo-romantic or symbolist poetry in German, Stefan George and Hugo von Hofmannsthal were espousing them. When Lublinski turned his back on Dehmel, so to speak, he added, ‘any discussion of the lyric poetry of the future for the moment means a discussion of the poetry of Stefan George’. Dehmel and George were openly hostile to each other; Dehmel’s second wife, Ida Auerbach, had once been one of George’s muses, so there are personal as well as professional reasons for George’s description of Dehmel’s work as ‘amongst the worst and most objectionable writing I have ever read’. Hofmannsthal was for several years caught between the two poets, and his behavior is almost a yardstick for the differences between them. When Hofmannsthal’s relations with George were cool, his correspondence with Dehmel livened up; when Hofmannsthal and George were on good terms, he dropped the correspondence with Dehmel. Their works were so different in style that, in the words of Julius Bab, ‘all serious connoisseurs of the arts in Germany are divided into those who admire Dehmel and those who admire George’. This was not true of Schoenberg, however. He wrote in 1913 that a poem by Dehmel stands at all the major turning points in his musical development, and it is clear that his settings of George mark an important stage in the transition to free atonality. How can it be that two such diametrically opposed writers occupy such important positions, especially as Schoenberg’s Viennese circle of friends included Adolf Loos and Karl Kraus, and the latter’s hostility to the artistic directions represented by George was implacable?

It remains therefore one of the most enduring ironies of Schoenberg’s choice of texts that the fifteen poems from the middle section of Das Buch der hängenden Gärten (The Book of the Hanging Gardens) set by Schoenberg in 1907-1908 (op. 15) were George’s particular homage to the woman who became Richard Dehmel’s wife and for whom he had written Weib und Welt, Ida Auerbach, née Coblenz. Astonishingly, Coblenz appears not to have understood that George was in love with her. She was naive enough, and uncomprehending enough about poetry, to recommend Dehmel’s Erlösungen to George at Christmas 1892. Three years later, she asked permission to send the poems she called ‘Semiramis-Lieder,’ which became part of Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, for publication in the journal Pan—edited by one Richard Dehmel. Dehmel wrote back saying, PAN does not want the same thing as He does by any stretch of the imagination. George believes he has a monopoly on ‘Art Itself’; we do not. In the house of our father Apollo there are many mansions! He wants art for art’s sake; we want art for life’s sake, and life takes many forms, and is by no means a temple for the initiates.

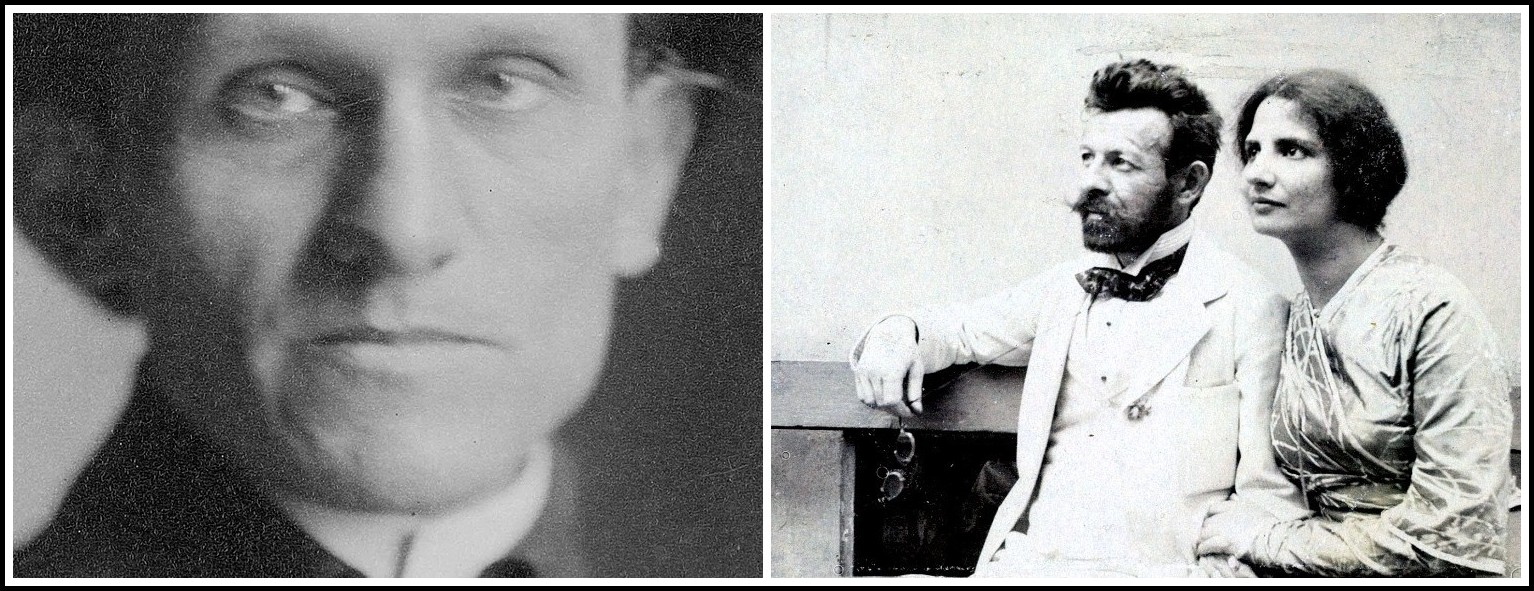

Stefan George | Richard & Ida Dehmel, 1901

It was after meeting Dehmel at Coblenz’s home in Berlin that George sent his last letter, implying that if she thought Dehmel ‘great and noble’ while he could only see the other poet as ‘coarse and vulgar,’ their friendship was at an end. They had no further contact, and Coblenz, after being wooed by Dehmel from 1898, possibly earlier, married him on 22 October 1901. This was the personal, the ‘biographical’, fallout from two incompatible conceptions of poetry and of two incompatible styles. Where Dehmel gushed and raged, George encoded and retrenched; Dehmel espoused the robust views of the Berlin literary circles, George influenced the development of neo-romantic and symbolist poetry in Vienna; Dehmel used all the formal latitude he felt he needed, George preferred traditional forms and understated rhythms. That Ida Coblenz could shift her attentions from George to Dehmel is only comprehensible if we accept she did not feel strongly for George in the first place; that Schoenberg could be seriously interested in both poets is at first sight quite inexplicable.

Richard & Ida Dehmel | Stefan George, 1899

The ‘Semiramis’ poems referred to by Ida Coblenz—so-called after the ninth-century Babylonian queen on whom Rossini’s Semiramide is loosely based—are the fifteen from Das Buch der hängenden Gärten set by Schoenberg, and are amongst the most erotic that George ever wrote. They occupy the middle section of the book, which itself is the third panel of a triptych, after Das Buch der Hirten und Preisgedichte (The Book of the Shepherds’ Songs and Hymns] and Das Buch der Sagen und Sänge [The Book of Legends and Songs], their context being the poet-king’s return to a familiar but exotic world, associated with youth. His soul is transformed, and he has a vision of freedom, of ‘offene bahnen / Nach den ersehnten höchsten stufen’ [open ways to the longed-for highest levels]. Before acceding to this realm, he is called temptingly by the voices of an earthly kingdom, by war, death, and sexuality. The imagery is strongly erotic.

Die leiber vor weiss des marmors mit bläulichen adern

Vom saftigen gelb der reife-beginnenden beeren—

Die leiber die hellrot wie blüten und hochrot wie blut.

The bodies of the white of marble with bluish veins,

of the juicy yellow of the berries beginning to ripen—

the bodies that are light red like blossom and deep red like blood.

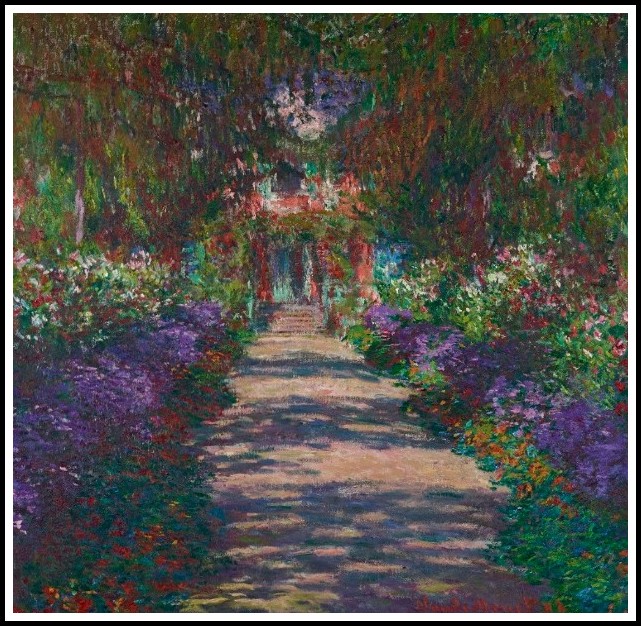

Monet, Pathway in Garden in Giverny, 1902

He resists, and there follow two poems in which his regal purity is reaffirmed and then, in the alternating rhythm that this section has, a poem that urges the poet to abandon his dreams of royal power and purity for a sybaritic life of sensuality. The last poem in this first section, ‘Friedensabend’ [Evening of Peace], describes a hot evening, dominated by threatening clouds, in which the voices from the suppressed destructive worlds call quietly to the poet—

Im dichten dunste dringt nur dumpf und selten

Bin ton herauf aus unterworfren welten.

In the dense haze there rises up only dully and rarely

a tone from subjugated worlds.

Monet, San Giorgio Maggiore at Dusk, 1912

—and the following fifteen poems, those set by Schoenberg, constitute an evocation of that rare and threatening tone, a love affair. This central section is dominated by the tension of desire and anxiety. The poet arrives as a novice.

STEFAN GEORGE 1: THE BOOK OF HANGING GARDENS – No. 3

All translations of the lieder in the following sequence are from Loralee Songer, Songs of the Second Viennese School (NY: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016)

Als Neuling trat ich ein in dein Gehege;

kein Staunen war vorher

in meinen Mienen,

kein Wunsch in mir,

eh ich dich blickte, rege.

Der jungen Hände Faltung sieh mit Huld;

erwähle mich zu denen, die dir dienen,

und schone mit erbarmender Geduld

den, der noch strauchelt

auf so fremdem Stege.

As a novice I entered your sanctuary;

no wonder showed

before my face,

no wish stirred in me

ere I saw you.

Look with favour upon my young clasped hands,

choose me to be among your servants

and protect with merciful patience

the one still stumbling

on so strange a path.

He is nervous, afraid to enter the territory of other men, but encouraged that the woman appears to be trying to meet his gaze, and prepares rich gifts of silk and roses for her. He is paralyzed by his desire.

STEFAN GEORGE 2: THE BOOK OF HANGING GARDENS – NUMBER 6

Jedem Werke bin ich fürder tot.

Dich mir nahzurufen mit den Sinnen,

neue Reden mit dir auszuspinnen,

Dienst und Lohn, Gewährung und Verbot,

von allen Dingen ist nur dieses not,

und Weinen, daß die Bilder immer fliehen,

die in schöner Finsternis gediehen,

wann der kalte, klare Morgen droht.

To all labors I am henceforth dead.

Calling you close with my senses,

To spin new tales with you,

Service and reward, permission and denial,

Of all things only this is needed,

And weep that the visions always flee,

Which flourished in the beautiful dark,

When the cold, clear morning looms.

The alternation of fear and hope keeps the poet in a state of near despair, and physical contact with his beloved is like a drug to which he has become addicted—‘Wenn ich heut nicht deinen leib berühre / Wird der faden meiner seele reißen’ [If I do not touch your body today, the thread of my soul will break] (Nr. 8). The blooms in a flower bed symbolize his love, strong stems with goblet-shaped heads, some velvety-soft, all emitting an enticingly sweet smell, but surrounded by erotic purple thorns.

STEFAN GEORGE 3: THE BOOK OF HANGING GARDENS – NUMBER 8

Wenn ich heut nicht deinen Leib berühre,

wird der Faden meiner Seele reißen

wie zu sehr gespannte Sehne.

Liebe Zeichen seien Trauerflöre

mir, der leidet, seit ich dir gehöre.

Richte, ob mir solche Qual gebühre?

Kühlung sprenge mir, dem Fieberheißen,

der ich wankend draußen lehne.

If I do not touch your body today,

The thread of my soul will break

Like an overstretched bowstring.

Let love tokens be mourning crepes

For me, who suffers, since I belong to you.

Consider whether I deserve such torture,

Spray cooling drops upon me, the fever-ridden,

Who, shaking, leans outside your door.

The eleventh poem is the consummation of their love—extraordinarily sexual writing from a poet normally so fastidious (it will be discussed further down)—and the last four evoke their gradual parting. The first of these [No. 12] enjoins the beloved to ignore the threats from outside: ‘denke der wächter nicht die rasch uns scheiden dürfen’ [do not think of the watchers who may quickly part us]; do not think either of the white sands that are ready to receive their blood.

STEFAN GEORGE 4: THE BOOK OF HANGING GARDENS – NUMBER 12

Wenn sich bei heilger Ruh in tiefen Matten

um unsre Schläfen unsre Hände schmiegen,

Verehrung lindert unsrer Glieder Brand:

So denke nicht der ungestalten Schatten,

die an der Wand sich auf und unter wiegen,

der Wächter nicht, die rasch uns scheiden dürfen

und nicht, daß vor der Stadt der weiße Sand

bereit ist, unser warmes Blut zu schlürfen.

When in blest repose in deep meadows

Round our temples our hands caress,

Reverence relieves the fire in our limbs:

So think not of the monstrous shadows

That, on the wall, rise and fall,

Nor of watchers who may part us in haste

Nor of the white sand beyond the town,

Ready to drink down our warm blood.

But she will not step into the boat he has prepared for her.

STEFAN GEORGE 5: THE BOOK OF HANGING GARDENS – NUMBER 13

Du lehnest wider eine Silberweide

am Ufer; mit des Fächers starren Spitzen

umschirmest du das Haupt dir wie mit Blitzen

und rollst, als ob du spieltest, dein Geschmeide.

Ich bin im Boot, das Laubgewölbe wahren,

in das ich dich vergeblich lud zu steigen…

die Weiden seh’ ich, die sich tiefer neigen

und Blumen, die verstreut im Wasser fahren.

You lean against a silver willow

At the shore, with the sharp points of the fan

You shield your head as if with bolts of lightning

And, as if you were playing, you twirl your jewelry.

I am in the boat that is protected by leafy vaults,

The boat into which I vainly invited you to step…

I see the willows that bow down lower,

And flowers that float, scattered, upon the water.

Despite his pleading, she talks of evanescent things like the leaves on the trees and the delicate mutability of the dragonflies.

STEFAN GEORGE 6: THE BOOK OF HANGING GARDENS – NUMBER 14

Sprich nicht immer

von dem Laub,

Windes Raub;

vom Zerschellen

reifer Quitten,

von den Tritten

der Vernichter

spät im Jahr.

Von dem Zittern

der Libellen

in Gewittern,

und der Lichter,

deren Flimmer

wandelbar.

Do not always speak

Of the foliage,

Booty of the wind;

Of the shattering

Of ripe quinces,

Of the footsteps

Of the destroyers

Late in the year.

Of the trembling

Of dragonflies

In thunderstorms,

And of the lights

Whose flickering

Is changeable.

‘Nun ist wahr dass sie für immer geht’ [Now it is true that she is leaving forever] and the poet is left alone inside his Garden of Eden with the night outside as clouded and muggy as it was when he began.

STEFAN GEORGE 7: THE BOOK OF HANGING GARDENS – NUMBER 15

Wir bevölkerten die abend-düstern

Lauben, lichten Tempel, Pfad und Beet

freudig sie mit Lächeln, ich mit Flüstern –

nun ist wahr, daß sie für immer geht.

Hohe Blumen blassen oder brechen

Es erblaßt und bricht der Weiher glas

Und ich trete fehl im morschen Gras.

Palmen mit den spitzen Fingern stechen.

Mürber Blätter zischendes Gewühl

jagen ruckweis unsichtbare Hände

draußen um des Edens fahle Wände.

Die Nacht ist überwölkt und schwül.

We inhabited the evening-dimmed

Arbours, lighted temple, pathway and flowerbed

Joyfully – she with smiles, I with whispering –

Now it is true that she is leaving forever.

Tall flowers pale or breach

The glassy surface of the pond pales and breaks

And I miss my step in the boggy grass.

Palms stab me with their pointy fingers.

The sibilant mass of friable leaves

Is whirled about erratically by unseen hands

Outside about the dull walls of Eden.

The night is clouded and sultry.

The last section of George’s Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, consisting of six poems, reasserts the ideal of purity that was adumbrated in the first section, but does so with characteristic ambivalence. The poet turns his back on erotic love, calling it ‘heidnische verzückung’ [heathen rapture] and regretting that it made him betray his calling, and ‘the sanctity of his office’. His distraction has meant that the enemy has invaded his kingdom, and he feels so weakened as to be unable to summon up again the heroism of section I, his only consolation is the perpetuation of his poetic gifts. He throws away his diadem and goes to serve another ruler as a slave: tempted to murder his new master, he resists, leaves the palace and makes his way to the river; on the way, in the symbolic breaking of a sycamore branch, he purifies himself of his sin. Leaving the community of men and women, the poet-king sits alone and contemplates the loss of his kingdom in the beautifully elegiac penultimate poem. Voices from the river call to the man who has lost love and promise him that they can reconcile ‘arms and words,’ love and art, with a ceremonial kiss.

Gustav Klimt, Island in the Attersee, 1901 | Stefan George

Schoenberg’s personal and professional circumstances in 1907-1908 made him particularly susceptible to the emotions depicted in this drama of desire and loss. He was on the verge of a breakthrough to atonal composition but did not have the necessary energy to bring it about, concerts aroused increasingly scandalized reactions, the critics were hostile, and his marriage to Mathilde von Zemlinsky was shaky. In 1932 he wrote in ‘Wie man einsam wird’ [How One Becomes Lonely]: I had had to fight for every work. I had been insulted by critics in the most disgraceful manner, I had lost friends, and I had given up every scrap of faith in the judgement of my friends. And I stood almost alone against a world full of enemies.

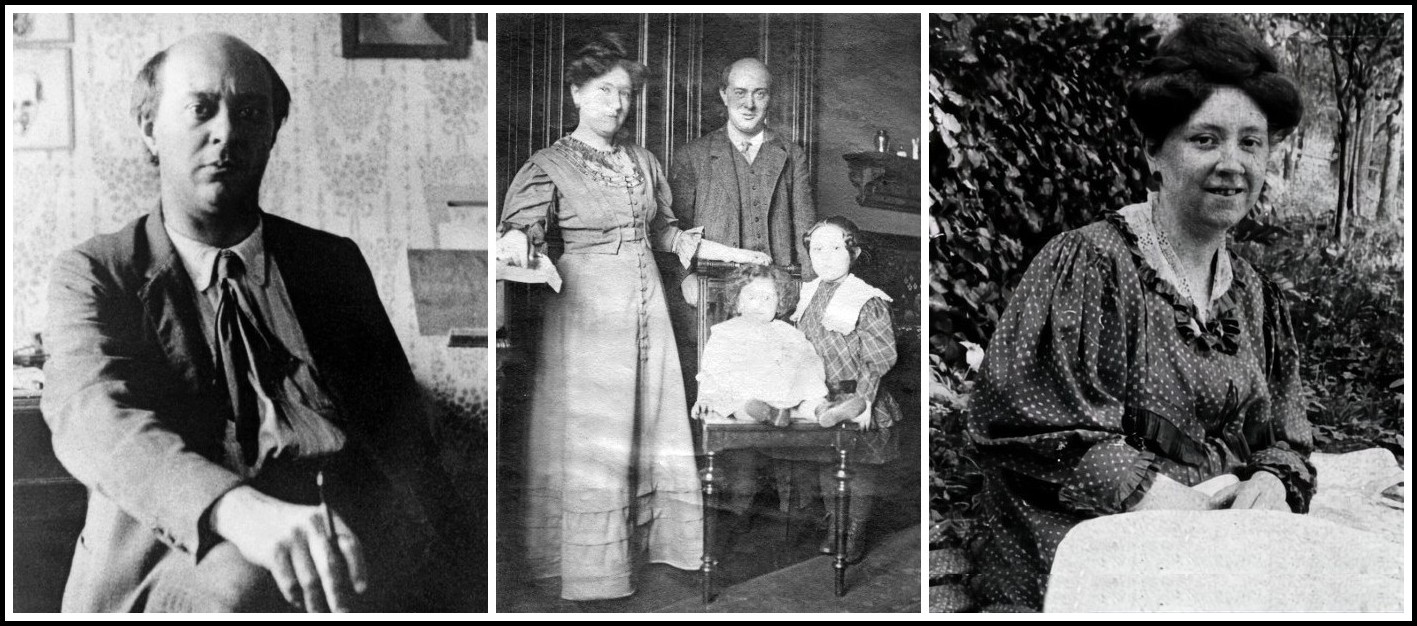

Arnold Schoenberg, 1907 | Mathilde & Arnold with Georg & Gertrude, 1907 | Mathilde Schoenberg

Before completing the George Songs, op. 15, Schoenberg had set ‘Ich darf nicht dankend an dir niedersinken’ [I must not sink down beside you in thanks] from Waller im Schnee (Pilgrim in the Snow]), as the first of Two Songs, op. 14 (in December 1907), begun two more settings, ‘Der Jünger’ [The Disciple] from Der Teppich des Lebens [The Tapestry of Life], and ‘Friedensabend’ [Evening of Peace], the last poem from section one of Das Buch der hängenden Gärten. He had also written the F-sharp minor String Quartet, op. 10 (March 1907—August 1908), whose third and fourth movements are settings of George’s ‘Litanei’ [Litany] and ‘Entrückung’ [Transportation] from Der siebente Ring (The Seventh Ring]. Schoenberg’s discovery of George, probably through the Ansorge Society, had opened up a poetic world of strong but controlled emotion, characterized by great formal and ethical rigor and above all by loneliness and the need for renunciation.

STEFAN GEORGE 8: FROM SCHOENBERG, OPUS 14: N° 1 – ICH DARF NICHT DANKEND

Translation taken from Bryan Simms, The Atonal Music of Arnold Schoenberg, 1908-1923 (OUP, 2000)

Ich darf nicht dankend

an dir niedersinken.

Du bist vom Geist der Flur,

aus der wir stiegen:

will sich mein Trost

an deine Wehmut schmiegen,

so wird sie zucken, um ihm abzuwinken.

Verharrst du bei

dem quälenden Beschlusse,

nie deines Leides Nähe zu gestehen,

und nur mit ihm und mir dich zu ergehen

am eisigkalten tiefentschlafnen Flusse?

I must not kneel in thanks

before you.

You came from the spirit of the fields,

from which we rose:

If I try to ease

your melancholy,

You turn away in rejection.

Must you remain

with your agonizing decision,

Never to acknowledge the nearness of your sorrow,

And only to walk with it and me

Along the river trapped in icy sleep?

‘Entrückung’—which opens with the famous ‘Ich fühle luft von anderem planeten’ [I feel air from another planet]—describes the total dissolution of the poetic identity in sound and movement and its eventual reestablishment as a passive element of the greater spiritual whole: ‘Ich bin ein funke nur vom heiligen feuer / Ich bin ein dröhnen nur der heiligen stimme’ [I am only a spark from the holy fire, I am only a rumble of the holy voice].

STEFAN GEORGE 9: SCHOENBERG, STRING QUARTET No. 2, Op. 10: IV. ENTRÜCKUNG | TRANSCENDENCE

Translated by Richard Stokes, author of The Book of Lieder

Ich fühle luft von anderem planeten.

Mir blassen durch das dunkel die gesichter

Die freundlich eben noch sich zu mir drehten.

Und bäum und wege die ich liebte fahlen

Dass ich sie kaum mehr kenne und du lichter

Geliebter schatten – rufer meiner qualen –

Bist nun erloschen ganz in tiefern gluten

Um nach dem taumel streitenden getobes

Mit einem frommen schauer anzumuten.

Ich löse mich in tönen, kreisend, webend,

Ungründigen danks und unbenamten lobes

Dem grossen atem wunschlos mich ergebend.

Mich überfährt ein ungestümes wehen

Im rausch der weihe wo inbrünstige schreie

In staub geworfner beterinnen flehen:

Dann seh ich wie sich duftige nebel lüpfen

In einer sonnerfüllten klaren freie

Die nur umfängt auf fernsten bergesschlüpfen.

Der boden schüttert weiss und weich wie molke.

Ich steige über schluchten ungeheuer,

Ich fühle wie ich über letzter wolke

In einem meer kristallnen glanzes schwimme –

Ich bin ein funke nur vom heiligen feuer

Ich bin ein dröhnen nur der heiligen stimme.

I feel air from another planet.

The faces that once turned to me in friendship

Pale in the darkness before me.

And trees and paths I loved grow wan

So that I hardly know them, and your light,

Beloved shadow – summoner of my torment –

Is now extinguished quite in deeper burning flames,

In order, after the frenzy of warring confusion,

To appear in holy awe and yearning.

I dissolve into tones, circling, weaving,

In groundless thanks and nameless praise,

Surrendering without a wish to the mighty breathing.

A tempestuous wind overwhelms me

In sacred rapture where the fervent cries

Of praying women in the dust implore:

Then I behold how misty clouds disperse

In the sun-suffused clear skies

That only embrace on the farthest mountain retreats.

The ground shudders white and soft as whey.

I climb across vast chasms,

I feel myself floating above the furthest cloud

In a sea of crystal radiance –

I am but a spark of holy fire,

I am but a thundering echo of the holy voice.

‘Litanei’ evokes the return of a pilgrim to the house of his lord; he is physically exhausted, weighed down by grief and desperate for peace, and the poem ends with a plea to replace the love he feels with the lord’s grace: ‘Töte das sehnen – schliesse die wunde! / Nimm mir die liebe – gib mir dein glück!’ [Kill my longing, close my wound! Take my love from me and give me your grace!]. It is related to the stance of self-abasement described in ‘Der Jünger’. Schoenberg must have felt in 1907 that the emotional tenor established in these poems by George was one related to his own.

STEFAN GEORGE 10: SCHOENBERG, STRING QUARTET No. 2, Op. 10: III. LITANEI | LITANY

Translated by Richard Stokes, author of The Book of Lieder

Tief ist die trauer, die mich umdüstert,

Ein tret ich wieder, Herr! in dein haus…

Lang war die reise, matt sind die glieder,

Leer sind die schreine, voll nur die qual.

Durstende zunge darbt nach dem weine.

Hart war gestritten, starr ist mein arm.

Gönne die ruhe schwankenden schritten,

Hungrigem gaume bröckle dein brot!

Schwach ist mein atem rufend dem traume,

Hohl sind die hände, fiebernd der mund.

Leih deine kühle, lösche die brände,

Tilge das hoffen, sende das licht!

Gluten im herzen lodern noch offen,

Innerst im grunde wacht noch ein schrei…

Töte das sehnen, schliesse die wunde!

Nimm mir die liebe, gib mir dein glück!

Deep is the sorrow that darkens around me,

Once more I enter, Lord! thy house…

Long was the journey, weary now the limbs,

Empty the altars, full only the torment.

The parched tongue longs for the wine.

Hard was the struggle, numb is my arm.

Grant sweet repose to faltering footsteps,

For hungry mouths crumble your bread!

Weak is my breath calling forth the dream,

Hands are empty, feverish the mouth.

Lend thy coolness, quench the conflagration,

Cancel all hope, vouchsafe the light!

Fires in the heart still glow openly,

Deep within me a cry is still awake…

Kill all longing, close the wound!

Take love from me, give me thy joy!

Content aside, however, Schoenberg’s account of how his music arose in conjunction with George’s poetry, given famously in his essay ‘Das Verhiltnis zum Text’ [The Relationship to the Text] (1912), has curious similarities with the terms in which he accounted for his attraction to Dehmel’s poems in November 1913. The following predates his comments on Dehmel: A few years ago I was deeply ashamed to discover that in the case of some Schubert Lieder that were very familiar to me I had absolutely no idea of what was going on in the poems. When I had read these poems I found that it had not helped my understanding of these Lieder in the slightest, that I was not remotely required to alter my assessment of what the music presented. Quite the reverse: it was revealed to me that I had grasped the content, the true content, without knowing the poem, and had perhaps grasped it more profoundly than if I had remained on the surface of what thoughts the actual words were expressing. Even more decisive for me than this experience was the fact that I had completed many of my own Lieder intoxicated by the opening sounds of the first words of the text, without being remotely concerned with what happened in the rest of the poem, indeed without having even the faintest grasp of this in the midst of the whirl of composition. When one hears a line of a poem, a measure of a composition, one is able to grasp the whole. Thus I had perfectly assimilated the Schubert Lieder, poetry included, purely from the music, and perfectly assimilated Stefan George’s poems purely from their sound.

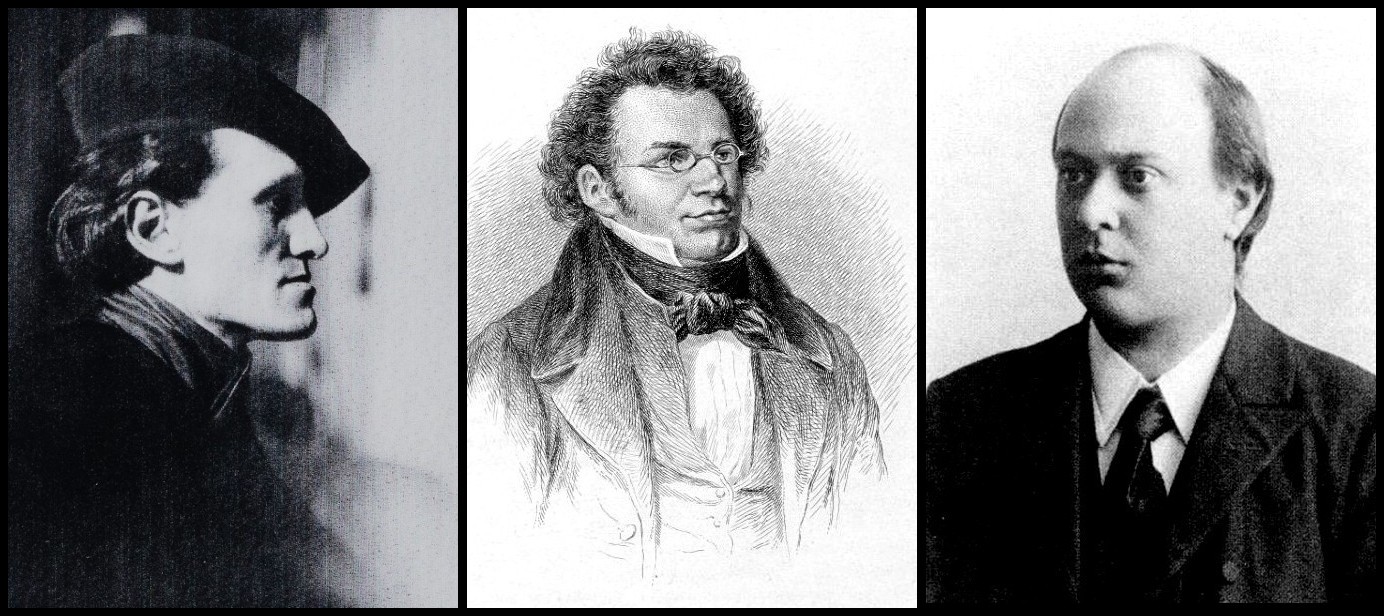

Stefan George | Franz Schubert | Arnold Schoenberg

The fact that most musicologists seem to accept what Schoenberg says without question does not invalidate the literary scholar’s near-astonishment at such a claim: it is prima facie highly improbable that complex texts, whose every carefully crafted syllable adds to and refines the complete meaning of the poem, can be fully grasped even after several very close readings. Yet in the context of the expressionist journal in which Schoenberg’s account first appeared, the desire to emancipate the music from the superficial ‘meaning’ of the text is quite comprehensible, and this context may account for the sense that Schoenberg is exaggerating. But George’s verse has a peculiar incantatory quality that may also account for the gist of Schoenberg’s remarks. Take the seventh of Das Buch der hängenden Gärten poems. The poem evokes the state of desperate longing that has overcome the central figure because of his physical and emotional dependence. The first two lines convey the disorientation partly by means of displacing the verb in each to the final position, as if they were both formally subordinate clauses; there is, however, no subordinating conjunction, and they must have the sense of main clauses. The third line contains the only normal main verb in the poem, upon which the four subordinate dass-clauses in lines 4-7 depend, and thus assures the tight structure of the poem as a whole. These last four lines look regular enough, a litany of misfortunes, but the second of them is the only line in the poem that is not a perfect iambic pentameter, since it has only four feet, Interrupting the pattern this way (and breaking up the strong ‘dass ich’ pattern and inverting subject and object) helps to convey an additional weariness. There are only three rhyme sounds in the poem, whose scheme is thus abbcacc, a deliberately lopsided and irregular pattern. The content is quite unremarkable, and there is hardly an image in the poem that could be called original, but the familiar symptoms of a lover’s distress are expressed with such technical skill that the import is quite idiosyncratic and fresh.

STEFAN GEORGE 11: THE BOOK OF HANGING GARDENS – NUMBER 7 (tr. Robert Vilain)

Angst und hoffen wechselnd mich beklemmen,

Meine worte sich in seufzer dehnen.

Mich bedrängt so ungestümes sehnen,

Dass ich mich an rast und schiaf nicht kehre,

Dass mein lager tränen schwemmen,

Dass ich jede freude von mir wehre,

Dass ich keines freundes trost begehre.

Fear and hope grip me in turn,

my words trickle away into sighs.

l am oppressed by a monstrous longing

so that I do not tum to rest and sleep,

so that tears flood my bed,

so that I push all forms of joy away,

so that I seek for no friend’s comfort.

Something similar can be said of the climactic eleventh poem. Again, the syntax makes the sense of the poem hover. It opens with a subordinate clause that forms part of a question—a question, moreover, that seems to cast doubt on the fact of their lovemaking. The memory of it is introduced slowly, the subject of the subordinate verb after ‘Ich erinnere dass’ is displaced by a comparison, ‘wie schwache rohren’; the ‘wir’ is unusually the penultimate word of its clause, but it has been anticipated in a strong position by ‘beide,’ emphasizing that the experience was fully shared. The trembling is conveyed partly by the sense, partly also by the alliteration of ‘b’ in ‘beide stamm zu beben wir begannen’. The deliciousness of the sensation and the slight haze of the memory is expressed partly by the use of ‘wenn’—this conjunction suggests that the trembling began whenever their bodies touched and not just at their first kiss. The penultimate line is also dependent on ‘ich erinnere,’ and the fact that the two memories are recalled side-by-side (instead of being linked, say, by ‘so that’) contributes to the subtle, but erotic, distancing of the experience. Lines 6 and 7 are also one foot shorter than the others, all iambic pentameters, which gives more urgency and allows for a meaningful pause before the full-length last line, more measured because of its five monosyllabic words.

STEFAN GEORGE 12: THE BOOK OF HANGING GARDENS – NUMBER 11 (tr. Robert Vilain)

Als wir hinter dem beblümten tore

Endlich nur das eigne hauchen spürten

Warden uns erdachte seligkeiten?

Ich erinnere dass wie schwache rohre

Beide stumm zu beben wir begannen

Wenn wir leis nur an uns rührten

Und dass unsre augen rannen—

So verbliebest du mir lang zu seiten.

When we at last felt only our own breathing

behind the garlanded gate,

did we experience the bliss we had imagined?

I remember that, like weak reeds,

the two of us began to shake even

when we touched each other lightly,

and that tears welled up in our eyes—

thus you remained for a long time at my side.

V. CONCLUSION

There is a clear progression both in subject matter and theme in the poets Schoenberg set most often between 1894 and 1909. They are all love poets: Ludwig Pfau the simplest, dividing his positive and negative emotions between poems; Dehmel tortured by the coexistence in the same collections, within single poems, of the delights of Eros and its dangers; George most subtly wrestling with both himself and the imminence of loss within the one collection. In each case, the technical means have developed to suit the new tenor of the material. George’s finely tuned verses are only apparently a return to old-fashioned styles, and in reality, they are the vehicles for a rarified and profoundly melancholy world view. His is also the world in which emotions are most delicately displaced by form.

Pierre Bonnard, The Garden, 1945 | Stefan George

The ‘content’ of each poet’s work does in many respects appear to match Schoenberg’s state of mind as he set them—but it does not do so necessarily. Had he set Dehmel in 1907, it would doubtless have been possible to account for this biographically: Dehmel, too, wrote poems that would suit a mood of embattled rejection. By bringing out some of the technical and stylistic features of these three poets, I have tried to suggest that there is at least another strand, besides content, to the development of Schoenberg’s taste. Equally, this enables us to take Schoenberg at his word when he says that he is less concerned with the content of the poetry and respect the sincerity and meaningfulness of his choice of poems at the same time. Whatever else Pfau, Dehmel, and George may have been, they were in a sense ‘strong’ poets. It is true that all write of troubled emotions and the two rivals were both beset by fears and anxieties. Nevertheless, none doubted the importance of poetry and his own ability to contribute to—in George’s case dictate—the canon. Schoenberg’s accounts of his response to poetry implies that this was a major factor in his choice, and suggests, too, that his literary taste was rather more developed than is usually acknowledged.

Camille Pissarro, Soleil levant à Eragny, 1894 | Arnold Schoenberg, 1924

ROBERT VILAIN: THREE BOOKS

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2024 | All rights reserved

Comments