Goodbye Pork Pie Hat | Crepuscule with Nellie | Blood Count

THE ELEGY IN MUSIC – PART 2 – JAZZ: MINGUS, MONK, STRAYHORN

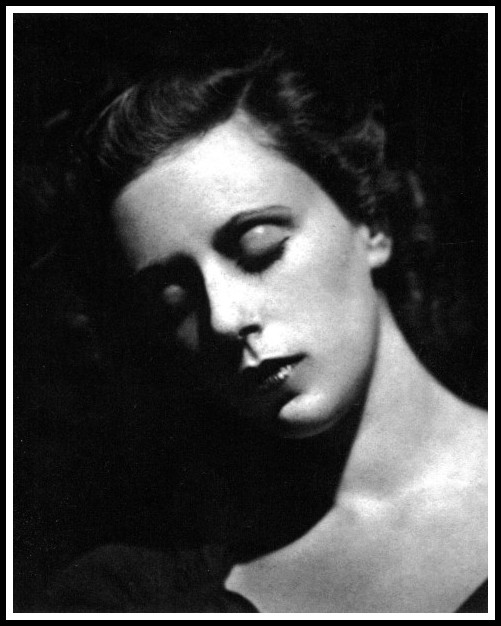

Pannonica de Koenigswarter, London, 1935

I. APPRAISAL

Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan is the author of the literary novel Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms

In this section I draw on the framework presented in The Elegy in Music – Part 1: A Fresh Perspective to offer my appraisal, as elegies, of ‘Goodbye Pork Pie Hat’ (Mingus), ‘Crepuscule with Nellie’ (Monk), and ‘Blood Count’ (Strayhorn). The sections that follow this one provide an analysis of the pieces.

MINGUS: GOODBYE PORK PIE HAT

‘Goodbye Pork Pie Hat’ is one of the finest elegies in all of music. Why? Because from beginning to end it holds in tension celebration and lament, the evocation of the subject’s individuality and the expression of the composer’s. And—above all—because the solitude it evokes through its stately dignity is far removed from any ‘atmospheric loneliness’: it is an expression of both the subject’s and the composer’s singularity.

MONK: CREPUSCULE WITH NELLIE

What makes ‘Crepuscule with Nellie’ such a fine elegy? The melody. As Roger Scruton writes, music without melody lacks the most important dimension of musical significance. Music is not a ‘sound effect’ but an expression of life, and melody is the principal sign of this. Melodies are the true musical individuals, the actors on the stage of music, whose life-stories are told by the notes.1 Indeed, listening to ‘Crepuscule with Nellie’, as ‘the notes tell the life-story of the melody’, I hear the ‘life-story’ of Thelonious and Nellie. Speaking of the Town Hall performance of the piece, Gérard Titus-Carmel describes Monk’s piano as patient and inexorable … sounding by itself like an orchestra: so how can one add to it without destabilizing the whole? How can one add a new orchestra around his, an orchestra that is only rhythm and force of attack against the sovereign fury of his solitude?2 The utter individuality of Monk’s melody, its angularity and edginess, is animated by a tension between ‘patient’ and ‘inexorable’, ‘fury’ and ‘solitude’, nostalgia and foreboding. The melody, along with Monk’s unique sense of tension and movement, largely accounts for the elegiac excellence of ‘Crepuscule with Nellie’.

1 – Roger Scruton, Understanding Music: Philosophy and Interpretation (London: Bloomsbury, 2016) p. 180

2 – Gérard Titus-Carmel, ‘D’un Monk, l’autre’. In Mystère Monk, ed. Franck Médioni (Paris: Éditions Seghers, 2022) p. 285. Translated here by Richard Jonathan.

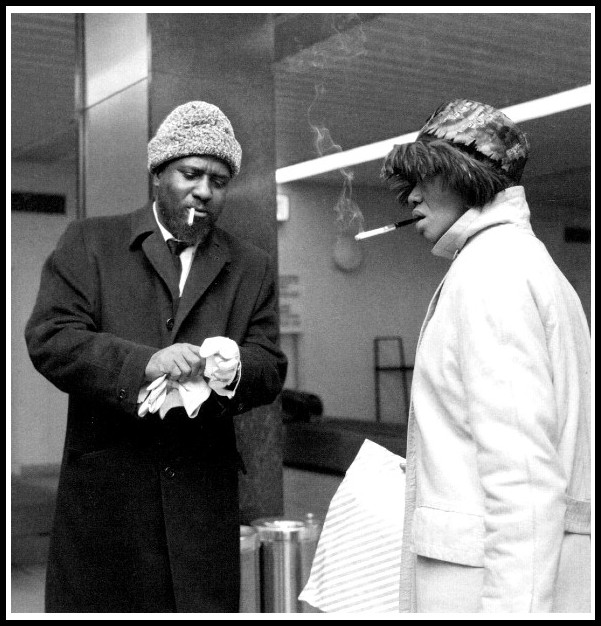

Thelonious Monk & Nellie, Paris, 1964 | Photo: Roger Kasparian

BILLY STRAYHORN: BLOOD COUNT

Billy Strayhorn composed a number of elegiac pieces of great beauty—‘Chelsea Bridge’ being one of the greatest—but it is ‘Blood Count’, the searing elegy he completed on his deathbed, that I find the most moving. Why? Because, in the interpretation I consider the finest—Stan Getz’s 1982 quartet recording of the piece on Pure Getz—revolt and resignation contend with each other in a scintillating tension. Ravaged by esophageal cancer, denied the recognition he deserved, Billy Strayhorn did not die ‘a good death’. As David Hajdu recounts, ‘Blood Count’, in its final form, is a wrenching moan, its pedal-point bass line evoking the rhythmic drip of intravenous fluid. And Strayhorn put away his music paper. “He did not write anything more after ‘Blood Count’,” said Marian Logan. “That was the last thing he had to say. And it wasn’t ‘Good-bye’ or ‘Thank you’ or anything phony like that. It was ‘This is how I feel,’ and he felt like shit—‘Like it or leave it’.”1 And yet, through its anger and despair, what comes through most clearly is a quiet dignity, a dignity that may not hold out a promise of redemption, but neither quite excludes it. The song walks a knife-edge, the funambule of Strayhorn’s soul balancing between bitterness and self-pity, but falling definitely into neither. ‘Blood Count’, like ‘Goodbye Pork Pie Hat’ and ‘Crepuscule with Nellie’, is one of the finest elegies in music and, like them, seems destined to endure for as long as art can defy time and death and the human soul resist self-abasement.

1 – David Hadju, Lush Life: A Biography of Billy Strayhorn (New York: Farrar Straus & Giroux, 1996) p. 253

II. GOODBYE PORK PIE HAT – CHARLES MINGUS

ARAM SAROYAN ON CHARLES MINGUS

In 1979, the last year of his life, Charles Mingus was dismayed when a radio commentator during a rebroadcast of a Mingus concert in New Orleans praised an early composition of his but got its musical lineage wrong, ‘I was inspired by Duke Ellington, Debussy, Stravinsky, Bartók,’ he said. ‘It had nothing to do with [jazz bassist] Oscar Pettiford.’ Ellington was his lifelong idol, and because Mingus also composed for the full orchestral palette, he is Ellington’s truest successor. His only rival, Thelonious Monk, was perfectly at home with the small ensemble (although his music is periodically the subject of successful orchestral settings). I remember seeing Mingus one night at Birdland during the 1960s. He stood with his bass to the left on a bandstand that included reeds, horns, and a rhythm section, and while his players had scores, Mingus would spontaneously call on soloists or indicate whole sections for particular emphasis or unrehearsed interludes. It was as if he was playing his bass and his orchestra simultaneously. His body of work is among the most emotionally protean with one of the most varied and informed musical pedigrees in American history. In addition to the influences he names above, his compositions embrace gospel, blues, R & B, salsa and Afro-Cuban strains—often in boldly articulated ‘movements.’ Works like ‘Fables of Faubus,’ ‘Self Portrait in Three Colors,’ ‘Reincarnation of a Love Bird,’ and ‘Sue’s Changes’ are new American classics.

From Aram Saroyan, Door to the River: Essays and Reviews from the 1960s to the Digital Age (USA: Black Sparrow Books, 2010) p. 51

BRIAN PRIESTLEY ON ‘GOODBYE PORK PIE HAT’

The creation of Goodbye Pork Pie Hat’ was set in motion on the bandstand at the Half Note Café, just after the quintet began a fortnight’s stay in mid-March 1959. Sy Johnson has repeated Handy’s account that ‘They were playing a very slow, minor blues and, in the middle of the tune, a man came in and whispered to Charles that Lester Young had died. And his response was, immediately, to start fashioning what became ‘Goodbye Pork Pie Hat’, and, by the time they were finished, the germ of it was there.’

From Brian Priestley, Mingus: A Critical Biography (Da Capo Press, 1982) p. 103

‘Goodbye Pork Pie Hat’ refers to the favored headgear of saxophonist Lester Young and was directly inspired by his slow, alcoholic self-destruction (a process terminated less than two months before the recording of Mingus Ah Um in May 1959).

The memorable theme derives its effectiveness from an underlying tension between the seemingly simple blues melody and the yearning chord-sequence. As musicologist Andrew Homzy puts it, ‘Like Duke Ellington, Mingus was able to compose over the blues structure with such strength, beauty and sophistication that the listener is not aware of the music’s humble origins.’ Highlights of this particular realization are John Handy’s solo and the moment (2m42 from the start) when his flutter-tonguing is mirrored by the tremolo of Mingus’s bass.

From Brian Priestley, liner notes for the 1998 Columbia Records CD issue of Charles Mingus, Mingus Ah Um.

TODD JENKINS ON ‘GOODBYE PORK PIE HAT’

The tune lays a mutant blues theme upon a beautiful, very un-bluesy chord structure. The expansive initial chords are rich with 9ths and 13ths, and during the solo sections every chord is a 7th or minor 7th, which creates a notable harmonic density. Appropriately, the tenors of Handy and Ervin are the only horns to be heard, and the blending of sound is gorgeous.

From Todd S. Jenkins, I Know What I Know: The Music of Charles Mingus (USA: Greenwood Publishing) p. 64

III. CREPUSCULE WITH NELLIE – THELONIOUS MONK

ROBIN D.G. KELLEY ON ‘CREPUSCULE WITH NELLIE’

Monk had started composing a piece for Nellie just when she fell ill. He worked on it throughout the month of May 1957 between home and the Algonquin, and Nica captured a ‘draft’ of it on tape during one of Coltrane’s visits. He wanted to call it ‘Twilight with Nellie,’ but the Baroness promptly suggested he use the French word for twilight: crépuscule. It became his obsession. He conceived of it as a through-composed piece—there would be no improvisation, no variation, just a concise arrangement. ‘Crepuscule with Nellie’ was to be his concerto and he wanted it to be perfect. Driven to mania, he stayed up many nights wrestling with the song’s middle or bridge. He was desperate to finish the song because he feared he might lose his precious wife. Monk kept tinkering with ‘Crepuscule’ right up to his Riverside record date on June 25. He had stayed up several nights prior stressing over the music and out of sorts in Nellie’s absence. Finally, all of Monk’s fretting over ‘Crepuscule with Nellie’ paid off. Every part of the song is carefully orchestrated, from the bass counterpoint figures to the voicings to the little fills thrown in at various points. He plays a chorus and a half with just the rhythm section and then adds the horns for the next chorus and a half. The horns are not always together and sound somewhat tentative, but it does not detract from the composition’s haunting melody, descending harmonies, rhythmic displacements, and its odd thirty-three-bar structure and five-bar coda. When Nellie finally heard it on record, she smiled.

Robin D.G. Kelley, Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original (pp. 221-23). Aurum Press. Kindle Edition.

Nellie & Thelonious Monk, Milan, 1964 | Photo: Roberto Polillo

RAN BLAKE ON ‘CREPUSCULE WITH NELLIE’

Nellie Monk was a great source of strength to her husband. ‘Crepuscule with Nellie’1, written while she was recuperating from an illness, may be Monk’s most harmonically rich composition; the parallel sixths in bar 1, which set the mood, are certainly not a typical Monk device. He creates harmonic ambiguity by starting on a II major chord, not even introducing the flat 7th for a couple of beats. The dissonant interjection at the end of bar 2 is probably something that only Monk could have thought of. At first glance it seems foreign to the rest of the tune, but in fact it provides the vital spur that keeps listeners on the edges of their seats.

1 – This is Monk’s only through-composed piece, so no specific recording is referenced here.

From Ran Blake, ‘The Monk Piano Style’ in The Thelonious Monk Reader, ed. Rob van der Blieck (Oxford University Press, 2001) p. 254

Thelonious Monk, ‘Crepuscule with Nellie’ | © 1958/1986 Thelonious Music Corp.

LAURENT DE WILDE ON THELONIOUS MONK

Monk is inimitable. He is one of a kind, unique. I know 50 Miles Davises, 73 Charlie Parkers, and 54 John Coltranes in all the major capitals of the world. But there aren’t any Monks. He is much too independent to have a school. For a musician, a novice at the piano, working on Monk’s music is very difficult. The technical aspect is important. The way he places his body, the way he crosses his hands, the way he plays with his fingers—it’s a very unorthodox technique. I went to a Steinway store. They had a mechanical Steinway playing Monk. I heard this piano playing Monk. The notes were right, but it was not Monk. Why? Because the sound was missing. Monk’s incredible dynamics were not there, Monk who could strike one note with a 200-kilogram force and the next one with a force of just two grams. Fortunately, we have not yet been able to imitate Monk. His music, in that respect, cannot be assimilated.

From Laurent de Wilde, ‘Thelonious’. In Mystère Monk, ed. Franck Médioni (Paris: Éditions Seghers, 2022) p. 94. Translated here by Richard Jonathan.

Thelonious Monk, L’Olympia, Paris 1969 | Photo: Jacques Bisceglia

LAURENT DE WILDE ON ‘CREPUSCULE WITH NELLIE’

The symphonic (Town Hall Concert) ‘Crepuscule with Nellie’ is beautifully moving—Monk carries the whole band by himself, in a poignantly nonchalant rubato. This serenade to his wife, composed in 1957 when Nellie was in the hospital and Monk was left alone, can now be experienced in Technicolor and Panavision. But the critics who covered the Town Hall concert didn’t find the experience quite to their taste. Then again, the concept of a big band which amplifies the pianist’s playing was completely original. It had already taken time for people to get used to his piano style, and it would take a few more years to get the brassier version accepted. In fact, the piano itself represents the whole orchestra. Any composition teacher can show it to you on the keyboard: ‘Here is where the trombones are; the trumpets can go up to here, and the bass down to here’. That way, when you write music at the piano, you can always imagine that you have a big band at your fingertips. But here, it’s just the opposite: it’s the band that plays the piano! Arranger Hall Overton’s genius was his ability to harness the whole ensemble to the yoke of the piano.

From Laurent de Wilde, Monk, tr. Jonathan Dickinson (New York: Marlowe & Co., 1997) pp. 165-66

RADIO FRANCE REVIEW OF LAURENT DE WILDE’S ‘NEW MONK TRIO’

It is already twenty years ago now that Laurent de Wilde published his now-classic biography of Thelonious Monk and, a few years later, made a documentary on Monk for Arte Television. Ever since then, fans have been waiting for this homage to one of the greatest and most mysterious creators in American music. With much humility, Laurent de Wilde had already interpreted a number of Monk’s pieces over the course of his musical explorations, from acoustic versions of ‘Off Minor’ and ‘Jackie-ing’ to electronic versions of ‘Shuffle Boil’ and ‘Epistrophy’. New Monk Trio, released during the centenary of Monk’s birth, sees de Wilde tackling Monk’s timeless legacy over the course of an entire album. It is impossible, of course, to imitate Monk’s unique, mysterious sound; instead, the trio—Laurent de Wilde, piano; Jérôme Regard, bass; Donald Kontomanou, drums—reinvents, recomposes and rearranges Monk’s tunes, modifying the original tempo, changing the form, expanding the harmonies, and bringing different melodies together in one piece. Only ‘Reflections’ is not rearranged. And, as a final homage, Laurent de Wilde offers us a superb original composition for solo piano, ‘Tune for T’.

Fip (Radio France) October 2017

Of the many Monk-only albums, I find Laurent de Wilde’s New Monk Trio the freshest, the most exciting, and the most engaging (followed by Anthony Braxton’s Six Monk’s Compositions).

Richard Jonathan

IV. BLOOD COUNT – BILLY STRAYHORN

WALTER VAN DE LEUR ON ‘BLOOD COUNT’

Strayhorn wrote ‘Blood Count’ when he was seriously ill with esophageal cancer. It was his final work, scored at the Hospital of Joint Diseases on Manhattan’s Upper East Side in 1967.

From Strayhorn: An Illustrated Life, ed. A. Alyce Claerbaut & David Schlesinger (Chicago: Agate Bolden, 2015) p. 172

‘Blood Count’ is a forceful and tormented ballad that derives its expressive powers from typical Strayhornisms: a tightly composed dramatic melody against a lean but highly effective background. Its theme seems full of interrupted thoughts, and the fatalism of the unresolved descending line in the final bars seems to explore emotions not previously heard in Strayhorn’s work.

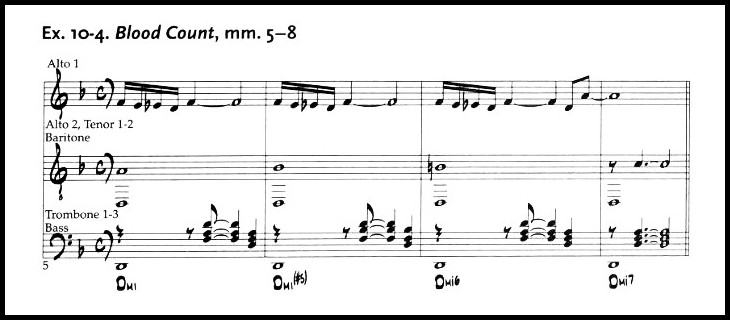

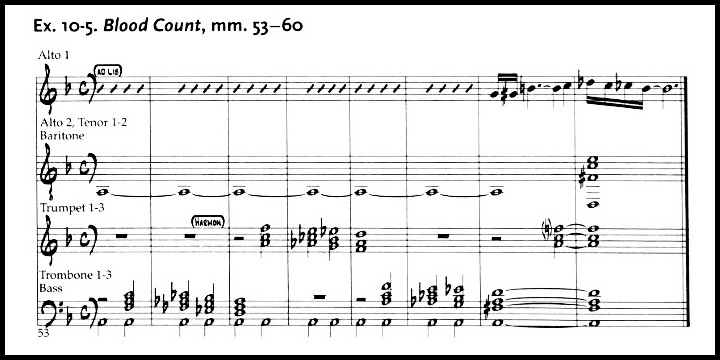

Much as all his earlier compositions seemed to resound a deeper biographical layer, in ‘Blood Count’ Strayhorn uses musical metaphors to express openly his feelings of sadness, frustration, and failure. ‘Blood Count’ is in D minor, a remarkable key since Strayhorn hardly ever used minor tonalities in his work. He confirms this minor key decisively in the second half of the first eight-bar strain, where a desperately repeated gesture spells out the interval between the minor third and the tonic (Ex. 10-4).

Blood Count, mm. 5-8

At the end of this first strain, Strayhorn uncharacteristically cuts off the alto’s line to jump back to the initial melody, without any harmonic or melodic connection. With this hard cut he deviates sharply from his compositional habits. ‘Blood Count’ grows increasingly unnerving in the bridge, with its anguished repeated descending gesture e”- f’-e’, and the ending is utterly unsettling: over a pedaled bass, the trombones and trumpets alternately play a line of desolate descending major triads that keep falling back to a D minor chord, suggesting that there is no escape (Ex. 10-5). With its dramatic melody and interrupted thoughts, and the fatalism of its the final bars, ‘Blood Count’ conjures the devastating consequences of Strayhorn’s progressing cancer.

From Walter van de Leur, Something to Live For: The Music of Billy Strayhorn (Oxford University Press, 2002) p. 171-72

Blood Count, mm. 53-60

Strayhorn’s invisibility during his long connection with the Ellington orchestra stands in marked contrast with his significance as a jazz composer. He possessed an advanced harmonic knowledge and paired his unfaltering talent for creating original melodies with a great rhythmic sensitivity. In addition, Strayhorn’s understanding of musical form and internal balance was staggering. But Strayhorn’s true forte lies in his capacity to weld all this knowledge and talent into naturally sounding, individual works, expressing the whole gamut of conflicting human emotions. With these means, Strayhorn composed some of the most sophisticated and meaningful works in the entire history of jazz.

From Walter van de Leur, Something to Live For: The Music of Billy Strayhorn (Oxford University Press, 2002) p. 182

MARIAN MCPARTLAND ON BILLY STRAYHORN

One of the first songs I played when I started working at the Hickory House in the early ‘50s was ‘Lush Life.’ I learned it from the Nat Cole recording. I hadn’t met Billy yet. I just loved the tune—such a beautiful, sad, and sophisticated tune. There’s a feeling in a lot of his music, a sadness, that is so raw and true that it tells you more about Billy than you could learn from meeting him. He was a wonderfully social person and always had a smile for everyone he met. But there was a regretfulness and unhappiness—a sadness inside him that comes across in his music. Just listen to ‘Lush Life’ or ‘Chelsea Bridge’ or ‘After All’ or ‘Passion Flower’ or ‘Blood Count.’ He wrote music that was wonderfully upbeat, too—’Take the ‘A’ Train.’ But a lot of people could write like that. Nobody else could write ‘Lush Life,’ not even Ellington. I’ve gotten in a lot of trouble for saying this, but I stand by it, and I’ll say it again. Strayhorn’s music is all his own, and it stands apart from Ellington’s music because it’s so deeply abstract and sophisticated.

From Strayhorn: An Illustrated Life, ed. A. Alyce Claerbaut & David Schlesinger (Chicago: Agate Bolden, 2015) p. 115

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2024 | All rights reserved

Comments