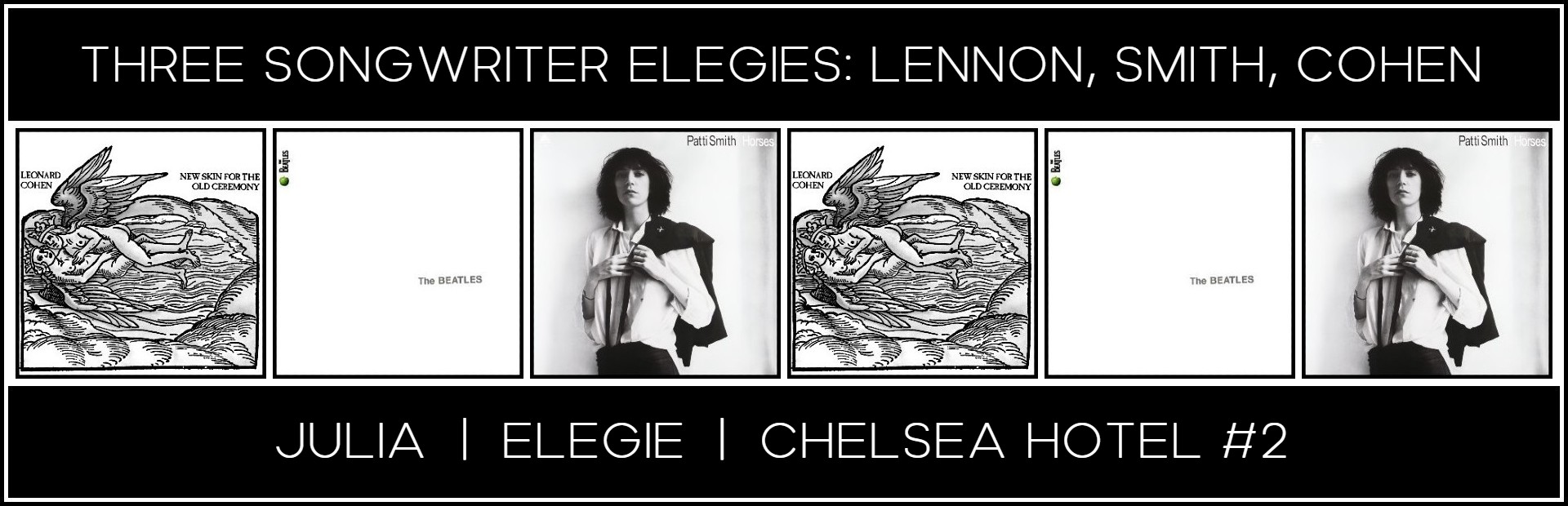

Julia | Elegie | Chelsea Hotel #2

THE ELEGY IN MUSIC – PART 4: JOHN LENNON, PATTI SMITH, LEONARD COHEN

Pierre Soulages, 2013

I. APPRAISAL

Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan is the author of the literary novel Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms

In this section I draw on the framework presented in The Elegy in Music – Part 1: A Fresh Perspective to offer my appraisal, as elegies, of ‘Julia’ (John Lennon), ‘Elegie’ (Patti Smith) and ‘Chelsea Hotel #2 (Leonard Cohen). The sections that follow this one provide an analysis of the pieces.

JOHN LENNON: JULIA

As a cultural figure, John Lennon’s significance, beyond his status as a composer of some of the twentieth century’s finest songs, lies in his experience of mourning and loss as manifested in his life and music. In ‘Julia’ he addresses, for the first time directly, the loss of his mother. Thanks to the security that Yoko Ono’s love procures him, he is able to open the door of the crypt at the core of his being, that kernel of loss where his mother lies. No sooner is she brought into the light than she is eclipsed: the song stages a transfer of love from Julia to Yoko. Neither woman is quite real—seashell eyes, windy smile; sleeping sand, silent cloud—the song is a freeze frame on a double exposure: Yoko translucent over Julia. ‘Julia’ is elegiac, not an elegy. Lennon will confront the Lacanian ‘Real’ of death two years later, in ‘Mother’. Then, the rage that the loveliness of ‘Julia’ suppresses will finally be given expression. ‘Mother’, then, is the true elegy for Julia.

Pierre Soulages, 2013

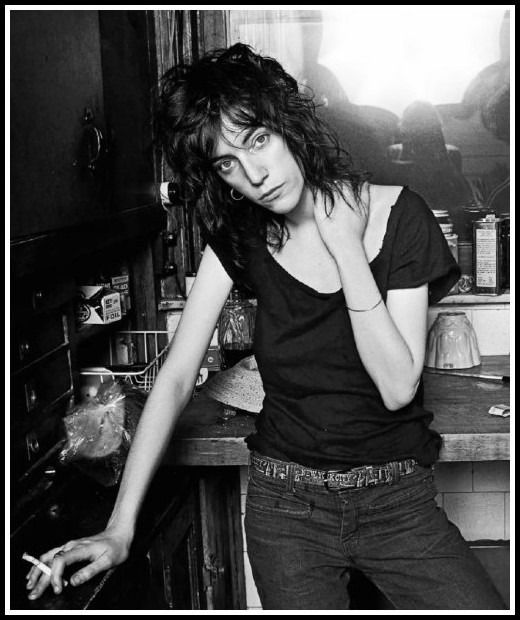

PATTI SMITH: ELEGIE

Patti Smith has a gift for memorializing, Rimbaud being the primary recipient of her penchant for paying homage. In ‘Elegie’, it is Jimi Hendrix that she remembers. And how! In all of rock, I can think of no finer elegy than this. Music—instruments and voice—and lyrics are seamlessly interwoven, given the song a compact, organic quality that largely accounts for its power. The poetry, welling up from a reservoir of feeling, resides equally in the music and the words. Despite its slow, meditative tempo, the elegy radiates the spirit of rock: no ‘prettiness’, no sentimentality, no striving for effect, just a virile femininity that recognizes that the heart, before being the seat of feeling, is a muscle. At once immanent and transcendent, feet on the ground and head in the clouds, ‘Elegie’, evidently, was made in a state of grace: its beauty may not be convulsive, but it nevertheless partakes of the miraculous.

Pierre Soulages, 2013

LEONARD COHEN: CHELSEA HOTEL #2

As a lyricist, Leonard Cohen, as his peers acknowledge, is peerless. It is not surprising, then, that out of a late-night encounter, never to be renewed, in a hotel room—her lips teaching him Latin, Southern Comfort presiding over the solidarity of the damned—he wrote an elegy that, in the richness of its resonance, outshines all sublunar laments. Cohen’s ethics emerge clearly in ‘Chelsea Hotel #2’. In line with the teaching of Zhuangzi,1 he accepts but does not hold, he allows things to pass without clinging to them, he keeps his vital capacity alert and communicative. It is this that makes the song an excellent elegy: it transcends lament and fosters lucidity, it eschews the comfort of the crowd in favour of individuality.

Pierre Soulages, 2013

II. JULIA – JOHN LENNON

Ian MacDonald

From Ian MacDonald, Revolution in the Head: The Beatles’ Records and the Sixties (London: Pimlico, 1998) pp. 285-86

Half of what I say is meaningless

But I say it just to reach you, Julia

Julia, Julia

Ocean child calls me

So I sing a song of love

Julia

Julia, seashell eyes

Windy smile calls me

So I sing a song of love

Julia

Her hair of floating sky is shimmering

Glimmering in the sun

Julia, Julia

Morning moon, touch me

So I sing a song of love

Julia

When I cannot sing my heart

I can only speak my mind, Julia

Julia, sleeping sand

Silent cloud, touch me

So I sing a song of love

Julia

Hmm-hmm-hmm

Calls me

So I sing a song of love

For Julia, Julia, Julia

The last of the sequence of folk-style finger-picking songs on The Beatles and the last number to be recorded for the double-album as a whole, ‘Julia’ is psychologically one of Lennon’s fulcrum pieces: a message to his dead mother telling her that, in ‘ocean child’ (the Japanese meaning of Yoko), he has finally found a love to replace her and that he can now relinquish his quasi-oedipal obsession (see ‘Yes It Is’).

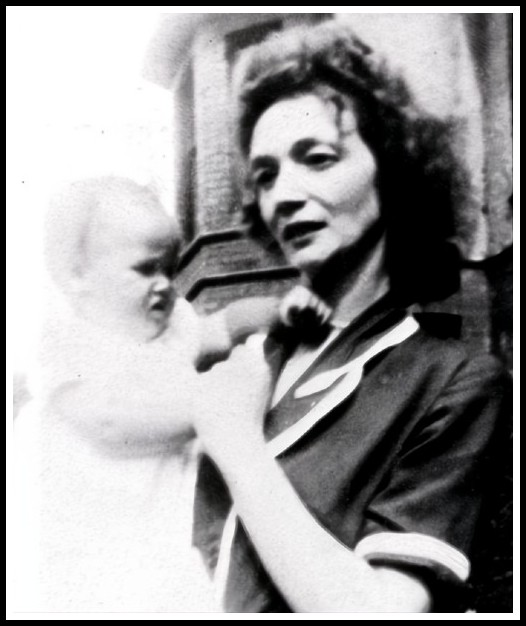

Julia, John Lennon’s mother, with Jacqui, his half-sister, 1950

Source: Julia Baird, John Lennon: My Brother (Grafton Books, 1988)

Born in 1914, Julia Stanley married Freddy Lennon in 1938, giving birth to John in 1940. When their marriage broke up two years later, John was adopted by Julia’s sister Mimi and her husband George Smith, and he went to live with them at Mendips, their house in Menlove Avenue.

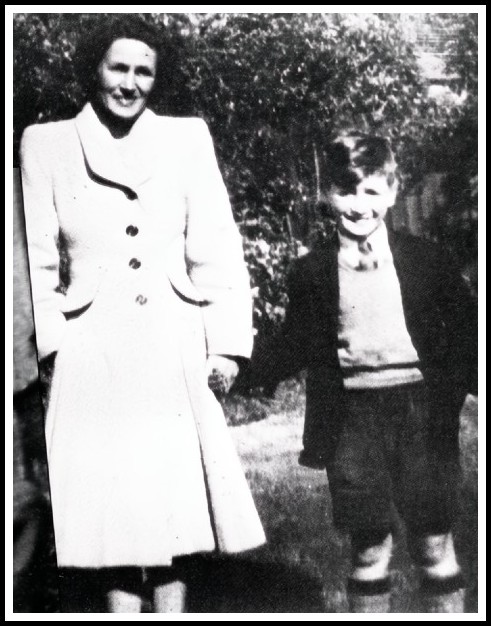

John Lennon with his aunt Mimi

Source: Julia Baird, John Lennon: My Brother (Grafton Books, 1988)

Meanwhile, Julia set up home with John Dykins, by whom she had two illegitimate children. When he was six, John became the subject of a fraught tug-of-love between his parents, at the height of which he ran after Julia in the street sobbing ‘Mummy, don’t leave me’. After this, while continuing to live with George and Mimi, he saw his mother more frequently.

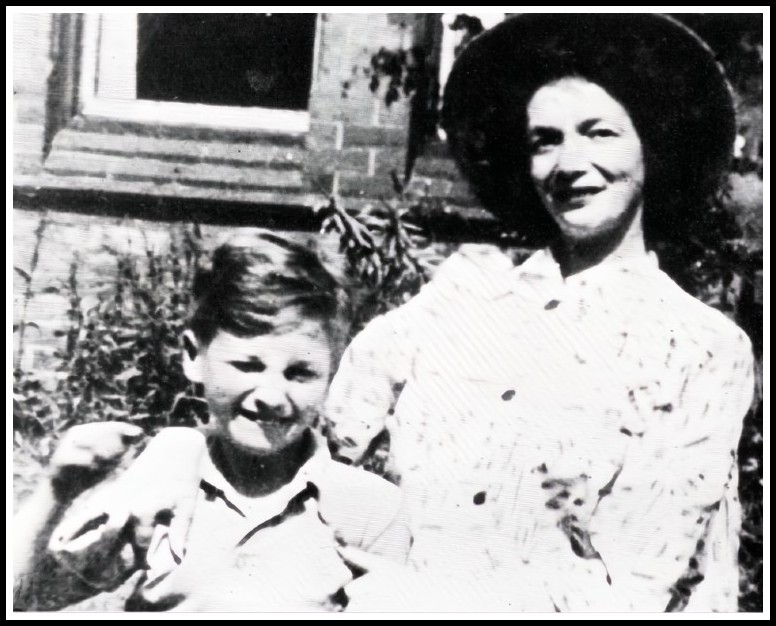

John Lennon c. 1950

Source: Julia Baird, John Lennon: My Brother (Grafton Books, 1988)

Following the second crisis in his life (Uncle George’s death in 1955), John and his mother grew closer. A free spirit, she was a laughing lover of life who positively encouraged the rebel in him. Siding with him and his friends against censorious adults, she followed the progress of The Quarry Men with genuine interest, teaching them tunes on her banjo. To John, Julia was a semi-dream-figure (‘a young aunt or a big sister’): the only human being he had ever loved without reservation. Her death in a road accident outside Mendips on 15th July 1958 shattered him, and for the next two years he was consumed by ‘a blind rage’, drinking wildly and incessantly getting into fights. That his new friend Paul McCartney had also lost his mother in his teens brought them close despite their temperamental differences, while The Beatles gave Lennon a sanity-saving purpose. However, his relationships with women, who found themselves endlessly measured against the incomparable Julia, remained angry and often violent.1

1 – According to McCartney, Julia was ‘a very beautiful woman, very good-looking, with long red hair. John absolutely adored her, and not just because she was his mum’.

John Lennon with his mother Julia, 1949

Source: Julia Baird, John Lennon: My Brother (Grafton Books, 1988)

‘Julia’, with which Yoko Ono helped,1 expiates Lennon’s tortured devotion to his mother. In the incantatory repeated notes of its intro, the song suggests an offering to an ancestral spirit: an attempt to break an obsession by commending the supplicant’s new earthly love in the hope of a blessing. The heart of this ritual—the transfer of Lennon’s love from Julia to Yoko—is its ten-bar middle where a quasi-oriental scale implies that the accompanying image (‘Her hair of floating sky is shimmering’) applies to both women: Julia in his boyhood memory, Yoko in his present and future thoughts. (Ono sent him many cryptic postcards while he was in India, one of which asserted that she was a cloud and that he should look for her in the sky.)2

1 – Her influence is detectable in the song’s haiku-like images. (She may have suggested ‘seashell eyes’, taken from the then-fashionable Lebanese mystical poet Kahlil Gibran.)

2 – The Oedipal aspect of Lennon’s love for Julia was replicated in his marriage to Ono (whom he called ‘Mother Superior’), she being frequently cast in a maternal role, an arrangement in which each colluded.

Julia, John Lennon’s mother (middle), with sisters Harrie and Nanny, 1949

Source: Julia Baird, John Lennon: My Brother (Grafton Books, 1988)

Lennon’s most childlike and self-revealing song, ‘Julia’ is almost too personal for public consumption. Nor did it succeed in laying his mother-fixation, as the exorcisms of ‘Mother’ and ‘My Mummy’s Dead’ on his first solo album prove.

MOTHER

John Lennon

Mother you had me, but I never had you

I wanted you, you didn’t want me

So I, I just got to tell you

Goodbye, goodbye

Father you left me, but I never left you

I needed you, you didn’t need me

So I, I just got to tell you

Goodbye, goodbye

Children don’t do what I have done

I couldn’t walk and I tried to run

So I, I just got to tell you

Goodbye, goodbye

Mama don’t go

Daddy come home…

To a great extent, Julia Lennon was her son’s muse. Once he had rid his soul of grief for her, his creativity forfeited its pressure and, during his more reconciled final decade, his output lost most of the edge and forcefulness it displayed at its fundamentally unhappy zenith in the mid-Sixties.

MY MUMMY’S DEAD

John Lennon

My mummy’s dead

I can’t get it through my head

Though it’s been so many years

My mummy’s dead

I can’t explain

So much pain

I could never show it

My mummy’s dead

III. ELEGIE – PATTI SMITH

Philip Shaw

From Philip Shaw, Horses (London: Bloomsbury, 33⅓, 2008) pp. 130-31

I just don’t know what to do tonight

My head is aching as I drink and breathe

Memory falls like cream in my bones, moving on my own

There must be something I can dream tonight

The air is filled with the moves of you

All the fire is frozen yet still I have the will

Trumpets, violins, I hear them in the distance

And my skin emits a ray, but I think it’s sad, it’s much too bad

That our friends can’t be with us today

Patti Smith, 1969 | Photo: Norman Seeff

Recorded on the sixth anniversary of Jimi Hendrix’s death, 18 September 1975, ‘Elegie,’ the last track on Horses, is, from a musicological point of view, the first true tune on the album. Circling around Am and B♭, Smith draws on her love of opera, inflecting the lyrics with a rich, harmonic diversity not encountered elsewhere on the album. The song belongs, however, as much to Richard Sohl and to Allen Lanier as it does to Smith. While the former contributes a beautiful, classically inspired piano arrangement, the latter performs a sonorous, elegiac guitar solo, reputedly devised and recorded in a single take. As a farewell offering to the record, as well as to Hendrix, Morrison, Rimbaud et al., the tone of the song could not be more appropriate.

Adopting a different voice for each line, Smith conveys a strong sense of the emotional complexity of loss, moving from blank desertion (‘I just don’t know what to do tonight’), through detached observation (‘Memory falls like cream in my bones’), to the sheer voluptuousness of grief (‘Moving on my own’); ‘Elegie’ is brought to a focus on the assertion of ‘will.’ Smith’s caustic intonation of the word is the cue for Lanier’s remarkable solo, accompanied by a wordless, expressive melody, conveying all the feeling that language leaves unsaid. When the singer returns to conventional lyrical expression, the flat, acidic tone is resumed, undercutting the potential for sentiment encoded in the final couplet (‘I think it’s sad, it’s much too bad / That our friends can’t be with us today’). Only here, again, the sense of toughness is displaced by the convulsive, extended sob on the song’s final syllable.

In the end, ‘Elegie’ suggests the futility of our attempts to come to terms with loss. Here, so-called closure is as perilous and fragile as the experience, death, that it seeks to comprehend and contain. Like its precursors in the elegiac poetic tradition, such as Milton’s ‘Lycidas’ (1638) and Shelley’s ‘Adonais’ (1821), Smith’s ‘Elegie’ is thus open-ended and radically decentered; it speaks disturbingly of the richness of death, of how loss can be transformed into profit; of how a singer can feed on the legacy of the dead (Morrison, Hendrix, Rimbaud), and of how declarations of self-reliance and autonomy (‘Moving on my own … I have the will’) are haunted and undermined by attendant feelings of guilt and sorrow. Horses could not have a finer conclusion.

IV. CHELSEA HOTEL #2 – LEONARD COHEN

Sylvie Simmons

From Sylvie Simmons. I’m Your Man: The Life of Leonard Cohen (London: Vintage, 2017) p. 189

I remember you well in the Chelsea Hotel

You were talking so brave and so sweet

Giving me head on the unmade bed

While the limousines wait in the street

Those were the reasons and that was New York

We were running for the money and the flesh

And that was called love for the workers in song

Probably still is for those of them left

Ah but you got away, didn’t you baby,

You just turned your back on the crowd

You got away, I never once heard you say

I need you, I don’t need you

I need you, I don’t need you

And all of that jiving around

I remember you well in the Chelsea Hotel

You were famous, your heart was a legend

You told me again you preferred handsome men

But for me you would make an exception

And clenching your fist for the ones like us

Who are oppressed by the figures of beauty

You fixed yourself, you said, ‘Well never mind,

We are ugly but we have the music.’

And then you got away, didn’t you baby,

You just turned your back on the crowd

You got away, I never once heard you say

I need you, I don’t need you

I need you, I don’t need you

And all of that jiving around

I don’t mean to suggest that I loved you the best

I can’t keep track of each fallen robin

I remember you well in the Chelsea Hotel

That’s all, I don’t even think of you that often

Leonard checked back into the Chelsea. Not many days passed before he noticed a woman who seemed to share his timetable, wandering the hotel at three in the morning looking for a drink and company. Janis Joplin had moved into the Chelsea while recording her second album with Big Brother & the Holding Company, which John Simon was producing. One night, as Leonard was on the way back to the hotel from the Bronco Burger and Janis from Studio E, they found themselves sharing the elevator, and then an unmade bed. In later years, after Leonard immortalized Janis’ blowjob in song—first in ‘Chelsea Hotel #1’, which he sang live but never released, then in ‘Chelsea Hotel #2’, recorded on 1974’s New Skin for the Old Ceremony—he polished the encounter into a stage anecdote. ‘She wasn’t looking for me, she was looking for Kris Kristofferson, I wasn’t looking for her, I was looking for Brigitte Bardot, but we fell into each other’s arms through some process of elimination.’ His words had the dark humour of both loneliness and honesty. Leonard’s later refinements to the anecdote were less black, more stand-up comedy. He said he asked her who she was looking for and when she told him he quipped, ‘My dear lady, you’re in luck, I am Kris Kristofferson.’ Either way, she made an exception.

Interestingly, the anecdotes followed a similar pattern to the songs. ‘Chelsea Hotel #1’ was the more open and emotional of the two:

A great surprise, lying with you baby

Making your sweet little sound …

See all your tickets

Torn on the ground

All of your clothes and

No piece to cover you

Shining your eyes in

My darkest corner

The second was more guarded and unsentimental—I can’t keep track of each fallen robin … / I don’t think of you that often—making the encounter sound humdrum, particularly when compared with the extravagance in his poem ‘Celebration’,1 where the orgasm from oral sex felled the protagonist ‘like those gods on the roof that Samson pulled down’. Leonard expressed regret on several occasions later at having named Joplin as the fellatrix and muse of the song. ‘She would not have minded,’ he said. ‘My mother would have minded.’ Quite possibly, but really it was Leonard who minded—not just at this rare lack of good manners, but at having revealed so much of the mystery, shown how the trick was done. Janis was a one-night stand and, it’s safe to say, not the only woman in the Chelsea to have given him head, yet something about her, or about what happened to her—less than three years later, at the age of twenty-seven, in a hotel room in Los Angeles, Janis Joplin OD-ed and died—seemed to have got under Leonard’s skin.

1 – See my discussion of Leonard Cohen’s ‘Light as the Breeze’, a discussion in which ‘Celebration’ is featured, in Leonard Cohen & Serge Gainsbourg: Song Comparison – Part 1.

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2024 | All rights reserved

Comments