Ever Fallen in Love & Boys Don’t Cry | Right & Shining Star | I’ve Seen That Face Before & Roxanne | Just Like Heaven & Beginning to See the Light | She Bop & Turning Japanese

Song Meanings

TWENTY SONGS PAIRED AND COMPARED: A THEMATIC ANALYSIS – PART 1

Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan is the author of the literary novel Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms

All paintings by Tommaso Fattovich. Posted by kind permission of the artist.

Tommaso Fattovich, Passed Me By, 2021

INTRODUCTION COMMON TO PARTS 1 & 2

Take two sets of ten songs. Pair each song from one set with a song from the other. Conduct a comparative analysis of the songs in each pair, focusing on a theme the pairing brings out. Aim to both instruct and delight the reader by the freshness and depth of the analysis.

That, dear reader, is what I will attempt to do in this comparative analysis of twenty songs. Of course, no interpretation of a work of art can ever be definitive. Think, therefore, of my interpretations as adventures in thought aimed at stimulating your own thinking, the idea being to enrich our appreciation of the songs.1

1 – Note that as the songs (together with the songs in ROCK SONGS AND SEX) originally made up the playlist for a fictional New Year’s Eve party that took place on 31 December 1987, only songs released before that date could be selected (one exception: ‘First We Take Manhattan’, released Feb. 1988). The fiction in question is, of course, my novel, Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms.

Twenty Songs Paired and Compared – Parts I & II – List of Songs

1. EVER FALLEN IN LOVE (FYC) | BOYS DON’T CRY (THE CURE)

EVER FALLEN IN LOVE

You spurn my natural emotions

You make me feel like dirt

And I’m hurt

And if I cause a commotion

I’ll only end up losing you

And that’s worse

Ever fallen in love with someone

Ever fallen in love

In love with someone

Ever fallen in love

In love with someone

You shouldn’t ‘ve fallen in love with

I can’t see much of a future

Unless we find out now

Just what’s to blame

And we won’t be together much longer

Unless we realize that we’re both the same

That’s what I’m saying

Ever fallen in love with someone

Ever fallen in love

In love with someone

Ever fallen in love

In love with someone

You shouldn’t ‘ve fallen in love with

Did you ever fall in love?

Did you ever?

BOYS DON’T CRY

I would say I’m sorry if I thought that it would change your mind

But I know that this time I have said too much, been too unkind

I try to laugh about it

Cover it all up with lies

I try to laugh about it

Hiding the tears in my eyes

‘Cause boys don’t cry

Boys don’t cry

I would break down at your feet and beg forgiveness, plead with you

But I know that it’s too late and now there’s nothing I can do

So I try to laugh about it

Cover it all up with lies

I try to laugh about it

Hiding the tears in my eyes

‘Cause boys don’t cry

Boys don’t cry

I would tell you that I loved you if I thought that you would stay

But I know that it’s no use, that you’ve already gone away

Misjudged your limit

Pushed you too far

Took you for granted

Thought that you needed me more, more, more

Now I would do most anything to get you back by my side

But I just keep on laughing

Hiding my tears in my eyes

‘Cause boys don’t cry

Boys don’t cry

Tommaso Fattovich, Shoots and Ladders, 2023

‘EVER FALLEN IN LOVE’ & ‘BOYS DON’T CRY’, OR KINDNESS & THE COUPLE

Expressing vulnerability is not the strong point of rock songwriters. And yet it is precisely the expression of vulnerability that, in governing the emotional climate of these songs, accounts for their greatness. Desire is a form of vulnerability, and kindness is the ability to bear vulnerability, that of others as well as one’s own.1 This dynamic—the interplay of desire and kindness—is what drives both ‘Ever Fallen in Love’ (1986) and ‘Boys Don’t Cry’ (1979).

What makes ‘Ever Fallen in Love’ touching is that the beloved has already left and the only one who doesn’t know it is the lover. Anyone who’s loved can relate to the song, for this phenomenon is inherent in the dynamics of the couple: ‘Separation is the repetition, in negative mode, of the surprise of love. “I’m leaving you” corresponds to “I love you”. Both are non-negotiable, both are impermeable to dialogue’.2 In the first verse, the lover acknowledges his rejection, his degradation, his hurt, but he fears that if he protests, the knowledge he has repressed—it’s already over—will return to overwhelm him: ‘You spurn my natural emotions / You make me feel like dirt / And I’m hurt / And if I cause a commotion / I’ll only end up losing you / And that’s worse’.

Tommaso Fattovich, Day Ride, 2023

In the second verse—‘I can’t see much of a future / Unless we find out now / Just what’s to blame’—he tries to take the high ground and salvage some dignity by pretending he can still be a subject and have his say in the fate of the couple. The ruse, of course, never works; the self-deception will only intensify the devastation to come. To that delusion the lover then adds another: he resorts to reason, as if love were amenable to rationality, and argues that the couple have to ‘find out now just what’s to blame’. To put a spin on Lou Reed, ‘You can reason all you want to, but I don’t love you anymore’.3

The pathetic then redoubles, as the lover asserts: ‘And we won’t be together much longer / Unless we realize that we’re both the same / That’s what I’m saying’. This is but another ruse to shore up the ruins of the relationship, for the pleading lover can never be on the same footing as the rejecting beloved, they can never be ‘the same’.4 The lover is in a heightened state of vulnerability, and the beloved has already moved on. What would kindness look like in this situation? I leave you, dear reader, to decide. For my part, I will simply point out that ‘all one-way love makes us aware of the universal strangeness of our state as a desiring being’.5

1- The phrasing of my argument is drawn to a large extent from a book by Adam Phillips and Barbara Taylor, On Kindness (London: Penguin Books, 2010).

2 – Franco La Cecla, Je te quitte, moi non plus (Paris: Calmann-Lévy, 2004). Translated here from the French by Richard Jonathan.

3 –‘You can hit me all you want to, but I don’t love you anymore’. Lou Reed, ‘Caroline Says II’ (Berlin)

4 – If one resorts to facts outside the song, as I generally refuse to do, the interpretation of this line could be that Pete Shelley is saying to Francis Cookson, the man he had lived with for seven years, ‘We’re both bisexual/gay, so why are you going to marry that girl? Admit it, you’re the same as me’. See BBC article, Pete Shelley: The story of Buzzcocks’ pansexual punk anthem Ever Fallen in Love.

5 – Franco La Cecla, Je te quitte, moi non plus (Paris: Calmann-Lévy, 2004). Translated here from the French by Richard Jonathan.

Tommaso Fattovich, Waves, 2023

In ‘Boys Don’t Cry’, the lyric perfectly captures the boy’s incapacity to assume the risks of love. Every one of the four verses expresses his preference for self-protection, his refusal to risk becoming vulnerable by being kind. What would kindness be in this context? Simply allowing the beloved to speak for herself. ‘I would say I’m sorry, but…’; I would break down at your feet, but…’; ‘I would tell you that I loved you, but…; ‘I would do most anything, but…’. All these ‘I would, but’ assertions are the rationalizations of an adolescent seeking to hide his own insecurity. Nevertheless, he does realize that without risk-taking there can be no love relation. He does take a degree of responsibility—‘misjudged your limit, pushed you too far, took you for granted’—and, as his tears attest, he does realize that fear inhibits the flowering of love. In ‘Boys Don’t Cry’, the boy’s ‘silent’ tears contradict his ‘voiced’ declarations, and therein lies the reason why the song is so successful in dramatizing the problematics of kindness and the couple (vulnerability and trust, hurting and being hurt). In its very structure, it shows that a person struggling to hold back their tears is more moving than one who cries. In both ‘Boys Don’t Cry’ and ‘Ever Fallen in Love’, then, words and music collaborate to evoke the complexity of love. Spastically dancing to the first tune, sensually to the second, the body may be mindless, but the songs leave us with something to keep in mind.

2. RIGHT (DAVID BOWIE) | SHINING STAR (EARTH, WIND & FIRE)

RIGHT

Taking it all the right way

Keeping it in the back

Taking it all the right way

Never no turning back

Never need no

Never no turning back

Flying in just a sweet place

Coming inside and sail

Flying in just a sweet place

Never been known to fail

Never been known

Never been known to fail

(Wishing) wishing you (wishing) that sometimes (sometimes)

Doing it, doing it right (doing it) one time (one time)

Gets you when you’re down

(Nobody, nobody, do it again, get it off)

Ah, sometimes, doing

Wishing sometimes (give it back)

Up there, up there (giving it)

Ah, my darlin’

(No) Ah, my darlin’ (giving it) ah (up there) aye

(Gimme, gimme) up there (yeah) gimme, doing

Taking with me (sometimes)

Loving it, doing it (right) till (take it) one time

Gimme (doing it)

Giving it (giving it back)

SHINING STAR

When you wish upon a star

Your dream will take you very far

When you wish upon a dream

Life ain´t always what it seems

Once you see your light so clear

In the sky so very dear

You´re a shining star, no matter who you are

Shining bright to see what you can truly be

What you can truly be

Shining star come into view

Shine its watchful light on you

Gives you strength to carry on

Make your body big and strong

Born a man-child of the sun

Saw my work had just begun

Found I had to stand alone

Bless it now I got my own

So if you find yourself in need

Why don´t you listen to these words of heed

Be a tiny grain of sand

Words of wisdom, yes I can

You´re a shining star, no matter who you are

Shining bright to see what you can truly be

Shining star for you to see, what your life can truly be

Tommaso Fattovich, Tippa My Tongue, 2022

‘RIGHT’ & ‘SHINING STAR’, OR THE TRAGIC & THE COMIC MODES

In literary theory,1 the tragic mode focuses on an individual structurally separated from society and struggling with himself. In the comic mode, the theme is the integration of society, with a focus on a central character struggling not with himself but with others.2 David Bowie is3 indisputably an artist and as such he is structurally an outsider.4 His struggle with himself is to realize his individuality as fully as possible via his artistic work and his way of life. In this sense, Bowie operates in the tragic mode. Earth, Wind & Fire, led by Maurice White, conceived of their music as aiming to convey ‘positive messages of love, spirituality, and self-empowerment, to serve and uplift humanity, guiding it through troubling times’.5 Their work aimed as social integration, empowering Blacks to assume their rightful place in American society. It has a collective orientation. EWF’s struggle is not with themselves but with others. In this sense, they operate in the comic mode.

‘Shining Star’ (1975) is an example of EWF’s positivity. To my ears, the music is fine but the lyrics come across as trite. While the chorus—‘You´re a shining star, no matter who you are / Shining bright to see what you can truly be’—is on a par with that of other ‘inspirational’ songs aiming to ‘uplift’, the verses are sub-par, even against pop music’s low bar: ‘When you wish upon a star / Your dream will take you very far / When you wish upon a dream / Life ain´t always what it seems / Once you see your light so clear / In the sky so very dear’. To put it kindly, that’s simply lazy writing. Of course, one cannot evaluate a lyric independently of the music it is integrated into, but one can speak of its effectiveness in the song. If many listeners are indeed ‘uplifted’ by the song, then it is indeed effective. For my part, however, I’m ill-at-ease with ‘positivity’. Why? Because such talk is cheap; it demands nothing of the listener, it doesn’t challenge. It tends toward sloganeering and preaching, practices that are not only antithetical to art bit untrue to life. I much prefer artists who, however ‘poetically’, tell it straight: James Brown, ‘Say it Loud (I’m Black and I’m Proud)’; Stevie Wonder, ‘Living for the City’; Marvin Gaye, ‘What’s Going On?’. On the whole, is Black American music more disposed to embrace ‘positivity’ than white rock and roll? Positivity, likely; joy, definitely.

1 – Northrop Frye, Anatomy of Criticism (Princton University Press, 1990 [1957])

2 – ‘Out of the struggle with oneself one makes tragedy; out of the struggle with others, melodrama’, goes an oft-cited aphorism.

3 – As I am writing about the work, I use the present tense, as I will for EWF.

4 – ‘I still haven’t become overground, really. I have just become the largest-selling of the underground.’ David Bowie in a 1976 interview in Sean Egan, Bowie on Bowie: Interviews and Encounters (London: Profile Books, 2015) Kindle Edition.

5 – Dwight Brooks, Earth, Wind & Fire’s ‘That’s the Way of the World’ (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 33⅓, 2022) Kindle Edition.

Tommaso Fattovich, The Clouds Will Drop Ladders, 2022

‘Right’ (1975) is from Young Americans, an album Bowie describes as ‘plastic soul’, a term his guitarist, Carlos Alomar, contests: ‘I defy that term and say that it was a true, authentic soul record’.1 Bowie adopted the idiom of soul music. ‘David was one of the first white artists they’d recorded at Sigma Sound Studios in Philadelphia. He was immediately accepted by the black community.’2 It may have been because he was immersed in that environment that he tempered his tragic mode—his ‘tarrying with the negative’3—and tried to convey a certain ‘positivity’: ‘Bowie said he wanted to put “a positive drone over” with “Right,” to write a success mantra. For whom? “Right” seems as much intended for its composer as its audience.’4 Indeed. Bowie never panders to his audience, never flatters them; instead, he challenges them, but challenging them is simply a side-effect of his challenging himself.

1 – Carlos Alomar in Dylan Jones, David Bowie: A Life (London: Penguin-Random House, 2018) p. 210

2 – Ava Cherry in Dylan Jones, David Bowie: A Life (London: Penguin-Random House, 2018) p. 214

3 – Hegel: ‘The living Spirit, the Substance made Subject, is living by virtue not of shrinking before the death inherent in its own dissolution, but of facing it head-on. “It wins its truth only when, in utter dismemberment, it finds itself. It is this power, not as something positive, which closes its eyes to the negative; on the contrary, Spirit is this power only by looking the negative in the face, and tarrying with it.”‘ Hegel, discussed and cited in Andrew Haas, Hegel and the Art of Negation: Negativity, Creativity and Contemporary Thought (London: I.B. Taurus, 2013)

4 – Chris O’Leary, Rebel Rebel: All the Songs of David Bowie From ‘64 to ‘76 (Winchester, UK: Zero Books, 2015) p. 374

Tommaso Fattovich, Space Octopus, 2024

So, even with the impetus to align himself with positivity, he simply cannot ‘betray’ his ‘tragic’ instincts. For example, the ‘natural’ title for the song would have been ‘The Right Way’, but Bowie simply calls it ‘Right’: the ‘natural’ title is far too preachy and, moreover, it sets itself up as an answer whereas for artists, questions are far more interesting than answers.1 But Bowie does much more than that to undermine positivity: he ‘dices and splices’ the lyric, fragmenting it, refusing discursiveness in the same way Picasso subverts the canons of realism. What’s more, thanks in part to the call-and-response between himself and the other singers, he does it in a way that is organic, not a gimmick. He systematically erases completion, he cultivates ambiguity: his ‘positive drone’, besides being a great dance song, at once affirms and undermines its positivity. If anyone still doubts Bowie’s genius, ‘Right’, if they’ve got ears to hear, will set them right.

1 – ‘One writes a novel when one does not have answers; when one has answers one writes an essay.’ Kamel Daoud, in an interview on French radio (France Inter, Le grand entretien) 28 August 2024. Translated here by Richard Jonathan.

3. I’VE SEEN THAT FACE BEFORE [LIBERTANGO] (GRACE JONES) | ROXANNE (THE POLICE)

I’VE SEEN THAT FACE BEFORE (LIBERTANGO)

Strange, I’ve seen that face before

Seen him hanging round my door

Like a hawk stealing for the prey

Like the night waiting for the day

Strange, he shadows me back home

Footsteps echo on the stones

Rainy nights on Hausmann Boulevard

Parisian music drifting from the bars

Tu cherches quoi, rencontrer la mort ?

Tu te prends pour qui, toi aussi tu detestes la vie

Dance in bars and restaurants

Home with anyone who wants

Strange, he’s standing there alone

Staring eyes chill me to the bone

Dans sa chambre, Joël et sa valise

Un regard sur ses fringues

Sur les murs, des photos

Sans regret, sans mélo

La porte est claquée, Joël est barré

ROXANNE

Roxanne

You don’t have to put on the red light

Those days are over

You don’t have to sell your body to the night

Roxanne

You don’t have to wear that dress tonight

Walk the streets for money

You don’t care if it’s wrong or if it’s right

Roxanne

You don’t have to put on the red light

Roxanne

Put on the red light

I loved you since I knew you

I wouldn’t talk down to you

I have to tell you just how I feel

I won’t share you with another boy

I know my mind is made up

So put away your make up

Told you once I won’t tell you again

It’s a bad way

Roxanne

You don’t have to put on the red light

Roxanne

You don’t have to put on the red light

Tommaso Fattovich, We Can Get Gum, 2022

‘I’VE SEEN THAT FACE BEFORE’ & ‘ROXANNE’, OR COMPLACENCY & RUTHLESSNESS

‘I’ve Seen that Face Before’ (1981) and ‘Roxanne’ (1978) both present an encounter with an ‘alien other’ who, I will argue, is a cover for the protagonist’s own alienated self. In the Grace Jones song, that someone is a stalker; in the Police song, a prostitute. ‘I’ve Seen that Face Before’ is a slice-of-life that shows the protagonist ruthlessly facing down her alien other (the stalker). ‘Roxanne’ is a fantasy that shows the protagonist complacently trying to ‘rescue’ his alien other (the prostitute).1

In both men and women, prostitutes inspire fantasy. A woman might wonder, ‘What is it like to lose my subjectivity and become an object, free of responsibility? What is it like to remove the limits to pleasure?’ A man’s fantasy might replace a sexual scenario with a rescue mission. This is the ‘white knight syndrome’, and it is evident in ‘Roxanne’: the guy wants to ‘rescue’ the girl from prostitution. ‘I loved you since I knew you’, he sings; ‘I won’t share you with another boy’. To persuade her to change her ways he resorts to morality: ‘You don’t care if it’s wrong or if it’s right’. It is this recourse to morality that reveals his complacency: morality, in fostering alienation, does not enable one to ‘become who one is’.2

‘Morality arises when goodness is lost’, said Lao Tzu, ‘goodness’ implying the ability to sustain the tension between the poles of a contradiction. That takes a certain maturity, a certain self-confidence—precisely what the guy lacks. He believes his moralizing can turn the Whore into a Madonna, one who will return his ‘love’. What he fails to grasp is that his desire to rescue Roxanne is a cover for his quest to face himself. She is the ‘alien other’ upon whom he projects what he has repressed (‘alienated’) in himself. Had he not resorted to morality, Roxanne, I suspect, would have had a thing or two to teach him. Faced with his complacency, she simply ignored him. Now, lest we forget, the song is a fantasy, an imagined encounter at the margins of the real. Were it more real, how would the story have ended? My guess is that the girl, a smirk on her face, would have told the guy to get lost, knowing full well that he already is.

1 – Readers may consider more appropriate a comparison of ‘I’ve Seen that Face Before’ with ‘Every Breath You Take’, since in both songs stalking is the central theme. If I chose ‘Roxanne’, it is because it highlights the protagonist’s view of the prostitute, just as ‘I’ve Seen that Face Before’ does the protagonist’s of the stalker. It is this aspect of the songs—their grounded point of view—that I find most interesting.

2 – Nietzsche, The Joyful Science.

Tommaso Fattovich, Yoppa, 2022

‘I’ve Seen that Face Before’ casts a cold eye on the clubbing scene in Paris.1 The protagonist is part of that scene, and her ‘alien other’, the stalker, is a caught in a cycle of anonymous sex, an antidote to loneliness that has now lost its effectiveness. ‘What are you looking for, a tryst with death? Who do you think you are, you’re sick of life just like the rest’:2 Does the protagonist include herself in ‘just like the rest’? The song suggests she does. Beyond the pursuit of self-soothing sex, then, it is the ‘sickness unto death’3—despair—that the protagonist shares with the stalker. It is in this sense that he is her ‘alien other’, the embodiment of the self she has ‘alienated’ in him (projected onto him).

Stalker and victim, despair and death, a couple interlocked: dimensions of tango, no doubt (see, for example, Last Tango in Paris). ‘In his bedroom, Jöel and his suitcase / A glance at his clothes / On the walls, photos / No regrets, no drama / The door’s slammed shut, Joël has split’.4 Who is Joël? The stalker? His lover? He’s taking his suitcase, so he’s not about to kill himself. Nevertheless, we have a sense of an ending. Stalkers, however, rarely give up: their modus operandi is escalation. And thus it is that ‘I’ve Seen that Face Before’ safeguards its mystery, a mystery that even dancing to it cannot unravel. The song suggests that stalking is an extreme of a continuum along which anyone who has yearned for intimacy can place themselves. And who has not yearned for intimacy? Indeed, stalking is rooted in a problematic experience of relationships:5 who has not had a ‘problematic experience of a relationship’?

In contrast to ‘Roxanne’, there is no complacent moralizing in ‘I’ve Seen that Face Before’. The protagonist is not seeking cover from what she’s afraid of in herself. On the contrary, in confronting it directly, she is ruthless. ‘I’ve Seen that Face Before’ casts a cold eye on reality, free of comforting fantasies.

1 – What the song shows can, of course, be found in any big city.

2 – My translation from the French.

3 – Kierkegaard

4 – My translation from the French.

5 – See Bran Nicol, Stalking (London: Reaktion Books, 2006) for an outstanding discussion of the subject.

4. JUST LIKE HEAVEN (THE CURE) | BEGINNING TO SEE THE LIGHT (THE VELVET UNDERGROUND)

JUST LIKE HEAVEN

‘Show me, show me, show me how you do that trick

The one that makes me scream’, she said

‘The one that makes me laugh’, she said

And threw her arms around my neck

‘Show me how you do it, and I promise you, I promise that

I’ll run away with you, I’ll run away with you’

Spinning on that dizzy edge

I kissed her face and kissed her head

And dreamed of all the different ways I had to make her glow

‘Why are you so far away?’ she said

‘Why won’t you ever know that I’m in love with you

That I’m in love with you’

You, soft and lonely

You, lost and lonely

You, strange as angels

Dancing in the deepest ocean

Twisting in the water

You’re just like a dream, you’re just like a dream

Daylight licked me into shape, I must have been asleep for days

And moving lips to breathe her name I opened up my eyes

And found myself alone, alone, alone above a raging sea

That stole the only girl I loved and drowned her deep inside of me

You, soft and lonely

You, lost and lonely

You, just like heaven

BEGINNING TO SEE THE LIGHT

Well, I’m beginning to see the light

Some people work very hard but still they never get it right

Well, I’m beginning to see the light

Now, now baby, I’m beginning to see the light

Wine in the morning and some breakfast at night

Well, I’m beginning to see the light

Here we go again, playing the fool again

Here we go again, acting hard again

Well, I’m beginning to see the light

Hey now, baby, I’m beginning to see the light

I wore my teeth in my hands so I could mess the hair of the night

Hey, well I’m beginning to see the light

I’m beginning to see the night

I met myself in a dream

And I just want to tell you everything was alright

Hey now, baby, I’m beginning to see the light

Here comes two of you, which one will you chose?

One is black and one is blue, don’t know just what to do

Well, I’m beginning to see the light

Yeah, yeah, baby I’m beginning to see the light

Some people work very hard but still they never get it right

Well, I’m beginning to see the light

There are problems in these times but none of them are mine

Oh baby, I’m beginning to see the light

Here we go again, I thought that you were my friend

How does it feel to be loved?

Tommaso Fattovich, Blondie, 2021

‘JUST LIKE HEAVEN’ & ‘BEGINNING TO SEE THE LIGHT’, OR VARIETIES OF ECSTATIC EXPERIENCE

Both ‘Just Like Heaven’ (1987) and ‘Beginning to See the Light’ (1969) convey an ecstatic experience. In the Cure song, ecstasy derives from l’amour fou—’beauty will be convulsive or not at all’—while in the Velvet Underground song, the ecstatic experience is that of having crossed a threshold in the mystic’s journey.

Robert Smith: ‘The song is about hyperventilating—kissing and fainting to the floor. Mary dances with me in the video because she was the girl, so it had to be her. The idea is that one night like that is worth a thousand hours of drudgery.’1 ‘Just Like Heaven’ celebrates that night; it is a mytho-poetic account of it. The song is sublime in that it transports us to a realm that discursiveness cannot reach, making idle any attempt to capture its effect in the language of reason. ‘The earth cannot escape the sky’, wrote Meister Eckhart, and as this ecstatic song reveals, an earthly experience can be ‘just like heaven’.

1 – Robert Smith to Johnny Black in Blender, 2003.

Tommaso Fattovich, Green Mountain Beauties, 2021

On the album The Velvet Underground, ‘Beginning to See the Light’ is set between ‘Jesus’ and ‘I’m Set Free’. The three songs constitute a trilogy, in that they are ‘spiritual in their desire for deliverance from the struggles of this world’.1 The lyric of ‘Jesus’ is a direct prayer: ‘Jesus, help me find my proper place / Help me in my weakness / ‘cause I’ve fallen out of grace’. The refrain of ‘I’m Set Free’ concludes: ‘I’m set free to find a new illusion’. In between these two songs, we have ‘Beginning to See the Light’. One can argue, then, that the joy expressed in the song is all the more ecstatic because the singer knows it will not last. This is a consistent theme in Lou Reed’s songs. In ‘I’m Waiting for the Man’, for example, he sings, ‘I’m feeling so good, feeling so fine / Until tomorrow but that’s just some other time’. Or these lines from ‘Wild Child’: ‘And then we spoke of kids on the coast / And different types of organic soap / And the way suicides don’t leave notes’. And these: ‘Then we spoke of movies and verse / And the way an actress held her purse / And the way life times can get worse’. And finally: ‘So we both shared a piece of sweet cheese / And sang of our lives and our dreams / And how things can come apart at the seams’. This lucidity—if one considers Ecclesiastes lucid—is the foundation of Lou Reed’s vision, and it this dark ground that gives his figures of light their intensity.

1– Anthony DeCurtis, Lou Reed: A Life (London: John Murray Press, 2017) Kindle Edition.

Tommaso Fattovich, Eyes Didn’t Let Me Open, 2023

In the outro of ‘Beginning to See the Light’ the singer repeatedly asks, ‘How does it feel to be loved?’. In ‘Love Makes You Feel’ (Lou Reed, 1972) he answers, ‘Love makes you feel ten foot tall’, and for good measure, gives us a sonic rush of acoustic guitar, bass and drum to make us hear what it sounds like. The experience of love, then, is one source of the song’s ecstasy; the other, as mentioned, is the experience of having crossed a threshold in the mystic’s journey. This journey is essentially a return to the source of being. In Sufism, the journey requires the pilgrim to traverse seven valleys: quest, love, knowledge, detachment, unity, amazement and annihilation. More generally, the sequence is purgation (of bodily desires), purification (of the will), illumination (of the mind) and unification (of one’s being with the divine). At what stage is the protagonist of ‘Beginning to See the Light’? In the Sufi scheme, it would be detachment: ‘There are problems in these times / But none of them are mine’. In the more general scheme, it would be illumination of the mind: ‘Some people work very hard / But still they never get it right’; ‘I met myself in a dream / And everything was alright’. And as the word ‘beginning’ suggests, the protagonist is aware of what he still has to work through: ‘Here we go again, playing the fool again / Here we go again, acting hard again’. And: ‘Here comes two of you / Which one will you chose? / One is black and one is blue / Don’t know just what to do’. Nothing, however, can restrain the joy of having reached a state of detachment and illumination. If the Cure in ‘Just Like Heaven’ express l’amour fou, the Velvet Underground in ‘Beginning to See the Light’ express the joie folle of a wanderer who’s found his way.

5. SHE BOP (CYNDI LAUPER) | TURNING JAPANESE (THE VAPORS)

SHE BOP

Well I see them every night in tight blue jeans

In the pages of a blue-boy magazine

Hey-hey, I’ve been thinking of a new sensation

I’m picking up good vibrations

O, she bop, she bop

Do I wanna go out with a lion’s roar

Yeah, I wanna go south get me some more

Hey, they say that a stitch in time saves nine

They say I better stop or I’ll go blind

O, she bop, she bop

She bop, he bop, we bop

I bop, you bop, they bop

Be bop—be bop—a—lu—she bop

I hope he will understand

Hey, hey, they say I better get a chaperone

Because I can’t stop messing with the danger zone

Hey, hey, I won’t worry, and I won’t fret

Ain’t no law against it yet

She bop, he bop, we bop

I bop, you bop, they bop

Be bop—be bop—a—lu—(she) bop

I hope he will understand

TURNING JAPANESE

I’ve got your picture, of me and you

You wrote, ‘I love you’, I wrote, ‘Me too’

I sit there staring and there’s nothing else to do

Oh, it’s in color, your hair is brown

Your eyes are hazel, and soft as clouds

I often kiss you when there’s no one else around

I’ve got your picture, I’ve got your picture

I’d like a million of you over myself

I want a doctor to take your picture

So I can look at you from inside as well

You’ve got me turning up and turning down

And turning in and turning ‘round

I’m turning Japanese

I think I’m turning Japanese

I really think so

No sex, no drugs, no wine, no women

No fun, no sin, no you, no wonder it’s dark

Everyone around me is a total stranger

Everyone avoids me like a psyched Lone Ranger

Everyone

That’s why I’m turning Japanese

I think I’m turning Japanese

I really think so

Tommaso Fattovich, Gulch, 2021

‘SHE BOP’ & ‘TURNING JAPANESE’, OR TEEN SENTIMENT & THE SINISTER

The teen underpinning of pop is most persistent, perhaps, when lyrics refer to masturbation. References to sexual intercourse have moved on from the allusiveness of ‘Let’s Spend the Night Together’, for example, but masturbation remains largely in the realm of the ‘clever’ phrase and coy metaphor, when not simply implied. ‘She Bop’ (1983) is a pre-Girl-Power ode to the practice. The adults’ admonitions—‘They say I better stop or I’ll go blind’; ‘They say I better get a chaperone’—are met by the teen’s statements of delight—‘new sensation’, ‘good vibrations’—and determination—‘Do I wanna go out with a lion’s roar / Yeah, I wanna go south get me some more’; ‘Hey, hey, I won’t worry, and I won’t fret / Ain’t no law against it yet’. Now who is the ‘he’ in ‘I hope he will understand’? Could it be the girl’s boyfriend? If so, is their situation akin to ‘Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow’? Hardly likely (that would be anachronistic), but could there be some parallel dynamic in play? The teen theme is highlighted in the allusion to ‘Be-Bop-a-Lula’ (Gene Vincent), but it is preceded by the more eighties sentiment of ‘everybody does it and it’s okay’: ‘She bop, he bop, we bop / I bop, you bop, they bop’. All in all, decidedly teen, with a lingering fifties ethos.

Tommaso Fattovich, Bloom, 2021

‘Turning Japanese’ (1980) has a sinister edge that derives from the guy’s difficulty in accepting that the girl’s gone. This is no ‘Pictures of Lily’ (The Who, 1967). Each successive verse ups the ante in ‘perviness’: ‘I sit there staring and there’s nothing else to do’; ‘I often kiss you when there’s no-one else around’; ‘I’d like a million of you over myself’; ‘I want a doctor to take your picture so I can look at you from inside as well’. Any lover who can’t let go after having been spurned will recognize that debasing the girl in one’s imagination is part of the process of coming to accept she’s gone. His masturbation will feed on a desire for revenge; it will be intensified by aggression and violence, if only symbolic.1 The notion of ‘turning Japanese’ can be interpreted as the guy’s way of ritualizing his aggression so as to make it more acceptable to himself.2 It can also be interpreted as ‘I’m not myself anymore, it’s not me doing this’ (therefore I’m not accountable to my ‘real’ self for what I’m doing).

1 – ‘Before’ and ‘after’ views of the picture he’s been masturbating to would reveal the extent to which his violence has been given sway.

2 – Via inscribing himself imaginatively in the samurai and martial arts traditions.

Tommaso Fattovich, Gorillas in the Mist, 2024

In ‘I Found Out’ (1970) John Lennon sings: ‘Some of you sit there with you cock in your hand / Don’t get you nowhere, don’t make you a man’. Note that even at his most starkly honest, Lennon says, ‘Some of you’ instead of ‘I’. It turns out that Lennon’s perception of masturbation as counterproductive self-soothing (in the context of his song) is an integral component of the dynamic underlying ‘Turning Japanese’. Of course, it’s perfectly understandable that David Fenton, the writer of the song, chose ‘not to go there’, as the ‘drive’ of the song works best (in terms of pop) when it stops just before the threshold of self-understanding. That is why the multiple repetitions of the chorus work so well: they take the masturbator to the threshold of orgasm but never let him go over the edge, leaving him at once frustrated in his bid to free himself of his obsession and revelling in the energy that frustration generates. That tension-loop is exactly the ‘emotion-dyad’ the listener experiences.1 This dynamic is largely what makes ‘Turning Japanese’ such a great song. Teen sentiment has, and will always have, its place in pop, but the edginess of the sinister, when derived from adult dynamics, is both more enduring and more engaging.

1 – Roxy Music’s ‘The Thrill of It All’ has a similar tension-loop.

Tommaso Fattovich, Kookaburra, 2023

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

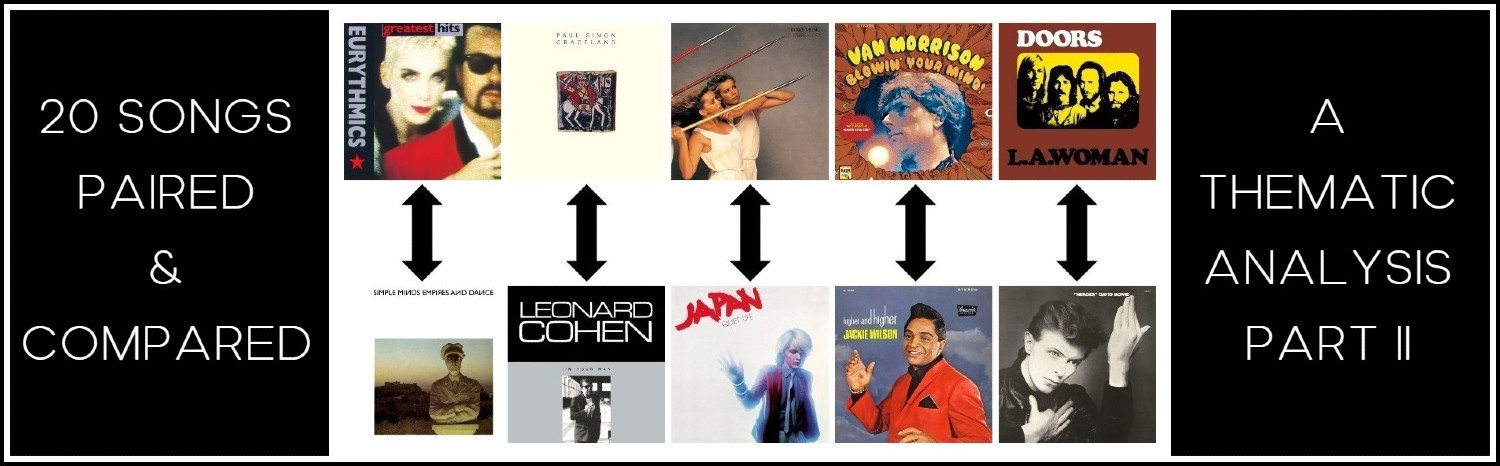

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2024 | All rights reserved

Comments