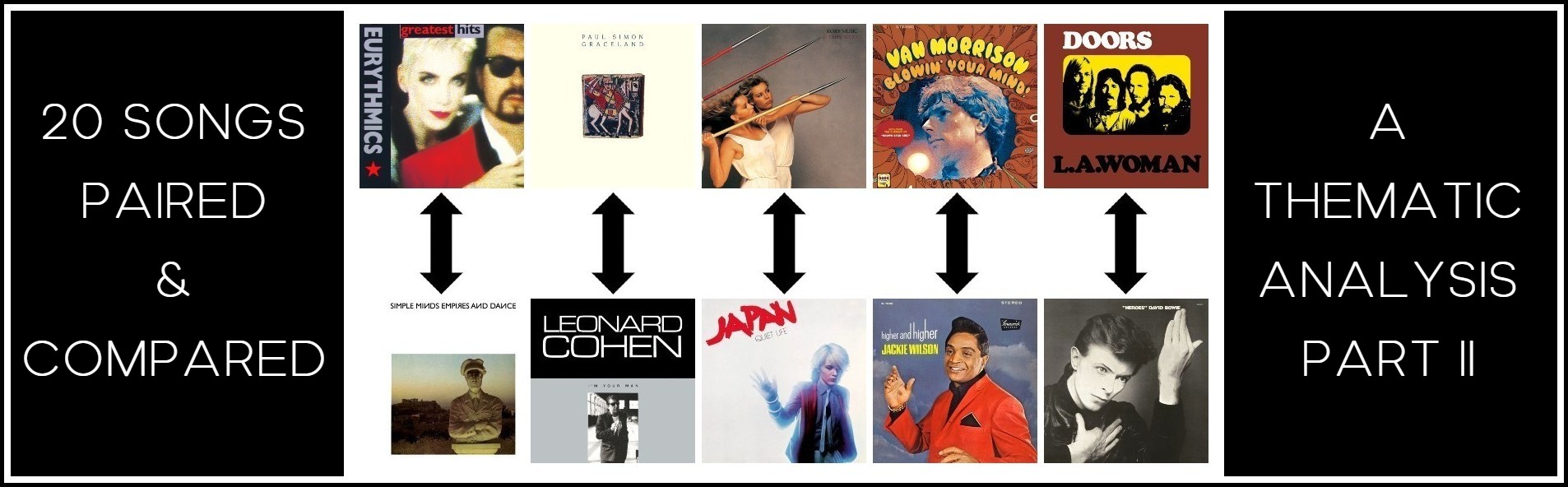

Sweet Dreams & I Travel | Boy in the Bubble & First We Take Manhattan | Same Old Scene & Quiet Life | Brown-Eyed Girl & Higher & Higher | L.A. Woman & ‘Heroes’

Song Meanings

TWENTY SONGS PAIRED AND COMPARED: A THEMATIC ANALYSIS – PART 2

Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan is the author of the literary novel Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms

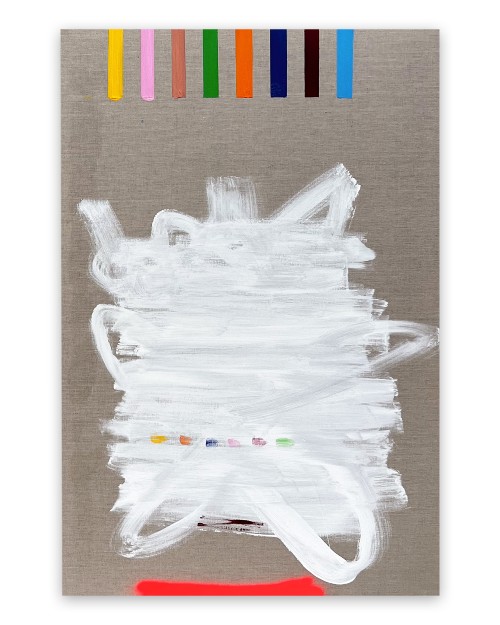

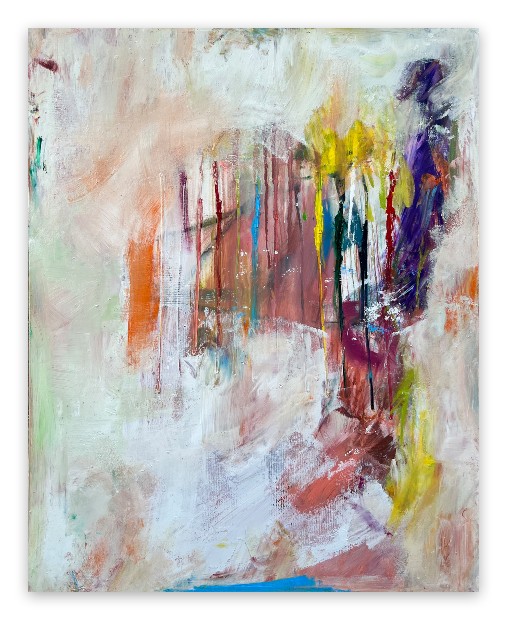

All paintings by Tommaso Fattovich. Posted by kind permission of the artist.

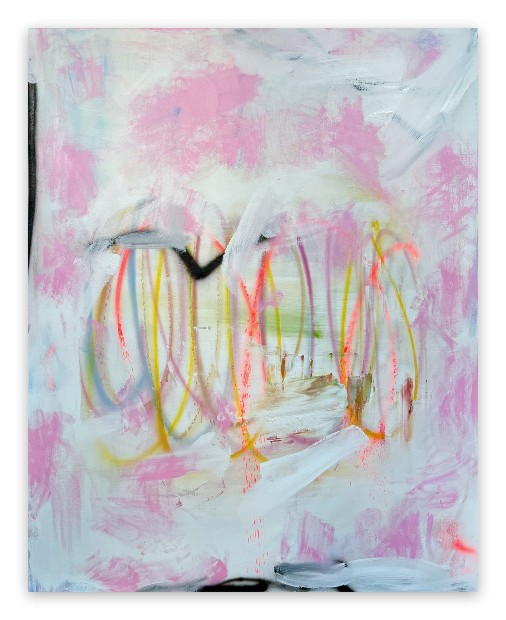

Tommaso Fattovich, Planted a Thought, 2023

INTRODUCTION COMMON TO PARTS 1 & 2

Take two sets of ten songs. Pair each song from one set with a song from the other. Conduct a comparative analysis of the songs in each pair, focusing on a theme the pairing brings out. Aim to both instruct and delight the reader by the freshness and depth of the analysis.

That, dear reader, is what I will attempt to do in this comparative analysis of twenty songs. Of course, no interpretation of a work of art can ever be definitive. Think, therefore, of my interpretations as adventures in thought aimed at stimulating your own thinking, the idea being to enrich our appreciation of the songs.1

1 – Note that as the songs (together with the songs in ROCK SONGS AND SEX) originally made up the playlist for a fictional New Year’s Eve party that took place on 31 December 1987, only songs released before that date could be selected (one exception: ‘First We Take Manhattan’, released Feb. 1988). The fiction in question is, of course, my novel, Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms.

Twenty Songs Paired and Compared – Parts I & II – List of Songs

6. SWEET DREAMS (EURYTHMICS) | I TRAVEL (SIMPLE MINDS)

SWEET DREAMS (ARE MADE OF THIS)

Sweet dreams are made of this

Who am I to disagree?

I’ve traveled the world and the seven seas

Everybody’s looking for something

Some of them want to use you

Some of them want to get used by you

Some of them want to abuse you

Some of them want to be abused

Hold your head up

Keep your head up (moving on)

Moving on

I TRAVEL

Cities, buildings, falling down

Ideal homes falling down

Those pictures I see on the wall

Timeless leaders standing tall

Assassin in a hit-and-run

Asia has a new-born son

Evacuees and refugees

Presidents and monarchies

Travel round, travel round

Decadence and pleasure towns

Tragedies, luxuries, statues, parks, galleries

Europe has a language problem

Talk, talk-talk, talk, talking on

In central Europe men are marching

Marching on and marching on now

Love songs playing in the restaurants

Airport playing Brian Eno

Travel round, travel round

Decadence and pleasure towns

Tragedies, luxuries, statues, parks, galleries

Tomasso Fattovich, Dame Mas, 2023

‘SWEET DREAMS’ & ‘I TRAVEL’, OR SEARCHING & OBSERVING

‘Sweet Dreams’ (1983) and ‘I Travel’ (1980) are both club-friendly songs, one synth-pop and the other disco-rock, yet each has an alienated quality, searching and questioning for the first, observing and recording for the second, that gives them a depth rarely found in club fare.

‘Sweet Dreams’ has a world-weary tone, as if resigned acceptance has ‘triumphed’ over nihilistic despair. ‘This is the way things are’, the singer seems to be saying, as if simply making a statement of fact. Yet her voice betrays the struggle she must have endured before arriving at understanding and acceptance. ‘Hold your head up / Keep your head up / Moving on’: These exhortations are sung as if the singer is advancing backward into positive belief. Half-hearted, they fail to convince, for we sense the cold eye of nihilism has not warmed sufficiently to advance forward into positivity. This feeling is reinforced by the multiple repetitions of the verses, as if, mantra-like, the singer is trying to persuade herself that her lucidity can dissipate the darkness. It is this juxtaposition of light and dark, warm and cold—in both the words and the music—that gives ‘Sweet Dreams’ its particular flavour. The body yields to the light and warmth, while the mind resists. Conversely, the mind yields to the darkness and cold, while the body resists. This is what I mean when I describe the song as having an ‘alienated’ quality. Moreover, the push-pull of this infinity-loop is reinforced by the fluid continuity of the synths and drum computer, while the voice, snaking in and out of the electro-lines, takes on a ‘ghost-in-the-machine’ quality. Between affirmation and negation, hope and despair, the song wavers; between the search and the find, the question and the answer, it refuses to choose. Where does that leave us, then? Free to dance in the magic circle of the entrancing song.

Tommaso Fattovich, Iridescent Armor, 2022

‘I Travel’ takes Donna Summer’s ‘I Feel Love’ and replaces the dreamy post-coital contentment with a feet-on-the-ground perspective on a Europe being roused from its slumber. Where ‘Sweet Dreams’ was world-weary and philosophical, distilling its new-found wisdom into a few well-wrought lines, ‘I Travel’ is quick-witted and practical, jotting down its observations on the fly. The result is a montage of images—‘tragedies, luxuries, statues, parks, galleries’—that convey the familiar through foreign eyes, producing a Brechtian V-Effekt (defamiliarization, distancing, alienation, making-strange). Love songs are juxtaposed with a military march, pleasure seekers with urban assassins; we see the decrepit in the venerable, the unsettled in the stable. The song reports the data received by the senses, it doesn’t ‘process’ it. The lyrics thus have a documentary status. This leaves the listener free to interpret them in light of their own knowledge and sensibility. What’s more, it allows the accretions of history to make of the lyrics a palimpsest, seen now, for example, through ‘layers’ of domestic terrorism, the fall of the Wall, or the rise of the far right. Tom Verlaine, David Byrne, Lou Reed—all made use of a similar ‘documentary’ and imagistic style; what gives ‘I Travel’ its distinction, in this regard, is that Jim Kerr could place his images, collage-fashion, on a repetitive loop, as it were, making it natural to dispense with narration. The form is ideal for reportage, for making observations, but it is far from artless: the rhymes provide rhythm, binding ‘random’ images into a coherent scheme. Alienated disco makes for artful techno. Far from mindless clubbing songs, then, both ‘Sweet Dreams’ and ‘I Travel’ reward close listening—assuming one can take a break from dancing to them.

7. BOY IN THE BUBBLE (PAUL SIMON) | FIRST WE TAKE MANHATTAN (LEONARD COHEN)

BOY IN THE BUBBLE

It was a slow day and the sun was beating

On the soldiers by the side of the road

There was a bright light, a shattering of shop windows

The bomb in the baby carriage was wired to the radio

These are the days of miracle and wonder

This is the long-distance call

The way the camera follows us in slo-mo

The way we look to us all

The way we look to a distant constellation

That’s dying in a corner of the sky

These are the days of miracle and wonder

And don’t cry baby, don’t cry, don’t cry

It was a dry wind and it swept across the desert

And it curled into the circle of birth

And the dead sand falling on the children

The mothers and the fathers and the automatic earth

These are the days…

The way we look…

It’s a turn-around jump shot

It’s everybody jump start

It’s every generation throws a hero up the pop charts

Medicine is magical and magical is art

The boy in the bubble and the baby with the baboon heart

And I believe

These are the days of lasers in the jungle

Lasers in the jungle somewhere

Staccato signals of constant information

A loose affiliation of millionaires and billionaires and baby

These are the days…

The way we look…

FIRST WE TAKE MANHATTAN

They sentenced me to twenty years of boredom

For trying to change the system from within

I’m coming now, I’m coming to reward them

First we take Manhattan, then we take Berlin

I’m guided by a signal in the heavens

I’m guided by this birthmark on my skin

I’m guided by the beauty of our weapons

First we take Manhattan, then we take Berlin

I’d really like to live beside you, baby

I love your body and your spirit and your clothes

But you see that line that’s moving through the station?

I told you, I told you, told you I was one of those

Ah you loved me as a loser, but now you’re worried that I just might win

You know the way to stop me, but you don’t have the discipline

How many nights I prayed for this, to let my work begin

First we take Manhattan, then we take Berlin

I don’t like your fashion business mister

And I don’t like these drugs that keep you thin

I don’t like what happened to my sister

First we take Manhattan, then we take Berlin

I’d really like to live beside you, baby …

And I thank you for those items that you sent me

The monkey and the plywood violin

I practiced every night, now I’m ready

First we take Manhattan, then we take Berlin

I am guided

Ah remember me, I used to live for music

Remember me, I brought your groceries in

Well it’s Father’s Day and everybody’s wounded

First we take Manhattan, then we take Berlin

Tommaso Fattovich, Doors and Distance, 2022

‘BOY IN THE BUBBLE’ & ‘FIRST WE TAKE MANHATTAN’, OR POETS IN TROUBLED TIMES

‘Boy in the Bubble’ (1986) is a poetic response to events the artist has witnessed or of which he has become aware. The first verse speaks of a terrorist attack in rhythmic lines driven by assonance (slow-sun, soldiers-side, bright-light, shattering-shop, bomb-baby, wired-radio). The second verse interpolates symbolic or abstract terms between the descriptive lines (circle of birth, automatic earth). In the third verse, ‘jump shot’ and ‘jump start’ foreshadow the ‘staccato signals’ of the fourth verse, while the next three lines suggest an affinity between medicine and art: means of healing by different means. The fifth and final verse resists elucidation; the violation of virgin land by monied predators is as good a suggestion as any. Now let’s consider the chorus. ‘Days of miracle and wonder’ suggests the artist remains an optimist; his faith that people can be their better selves is intact, no matter the horrors he has witnessed. ‘The long-distance call’ implies the poet is reporting from one world (the third) to another (the first). The intermediation of film or video—what comes between the eyewitness and the final viewer—is suggested by ‘the way the camera follows us in slow-mo / The way we look to us all’. The artist then suggests that in the big scheme of things what we are doing to each other and our world is of no great importance, but thanks to our capacity for ‘miracle and wonder’ we can still save the day, so ‘don’t cry, baby, don’t cry’.

Tommaso Fattovich, Root Down, 2022

‘First We Take Manhattan’ (1988) takes an altogether different approach to troubled times from that of ‘Boy in the Bubble’. The song picks the scabs on what the poet sees as a sick body politic. Leonard Cohen: In ‘First We Take Manhattan’ a kind of outsider is speaking, it’s somebody who never thought much of what he got. I can’t identify with it completely. In the context of the song it’s just the voice of enlightened bitterness. It is a demented, menacing, geopolitical manifesto in which I really do seriously offer to take over the world with any like spirits who want to go on this adventure with me.1 This is Cohen at his wittiest, at once responding to a question and undermining his answer: a song is not reducible to anything one can say about it. In that same interview he adds: The chorus refers to all those newsreel pictures we’ve seen of the dispossessed moving through the train station, the bag people on the most obvious level, the homeless on the most obvious level, the refugees on the most obvious level, but even those people in apparently more secure or profitable situations who feel that they have not yet arrived at any significant destination.2 As has often been pointed out, the protagonist of the song is a terrorist. It’s a fair guess that the type of terrorist Cohen had in mind was that of those active in western Europe in the seventies and eighties. The chapter headings of Jillian Becker’s book on the Baader-Meinhof gang give us, I believe, an indication of Cohen’s conception of terrorists at the time: Play the Devil. A Night at the Opera. Martyrs and Scapegoats. Mama’s Boy and the Parsons Daughter. A Little Night Arson. Fugitives. A Game of Sorrow and Despair. A Lefter Shade of Chic. Going Places and Doing Things. For Pity’s Sake. Killing. The Game Is Up, the Games Go On. Crocodile Tears. The title of the book is Hitler’s Children.3 I believe the poet who wrote Flowers for Hitler would have shared, at least to some extent, Jillian Becker’s vision of the Baader-Meinhof gang.

1 – Leonard Cohen in Jim Devlin, editor, Leonard Cohen in His Own Words (London: Omnibus Press, 1998) p. 60

2 – Ibid.

3 – Jillian Becker, Hitler’s Children: The Story of the Baader-Meinhof Terrorist Gang (London: Michael Joseph,1977)

Tommaso Fattovich, Bodhisattva Vow, 2023

Leonard Cohen’s ethics is grounded in the notion of individual responsibility. Neither in his work nor in his interviews does he ever make excuses, blame others or complain. He is rarely judgemental. Why? Because, as I deduce from reading and listening to him, he knows that ‘the line dividing good and evil runs through the heart of every human being’ (Solzhenitsyn). In ‘First We Take Manhattan’ he slips into the skin of a terrorist, someone who feels that they ‘have not yet arrived at any significant destination’ and aims to do so by committing terrorist acts. The terrorist denies individual responsibility: someone else is always to blame for others’ ills. Terrorists do not doubt: they banish ambiguity. Exactly the opposite of what an artist does. To spin a variation on an observation, ‘One becomes an artist when one does not have answers; one becomes a terrorist when one is sure one does’.1 Hannah Arendt wrote that ‘morally, the only reliable people when the chips are down are those who say “I can’t”.’2 The terrorist in the song, in his grandiloquence, cannot say ‘I can’t’. Nor is he capable of solitude, which Hannah Arendt defines as ‘the mode of existence present in the silent dialogue of myself with myself’.3 In this sense the terrorist, once again, is the antithesis of the artist. It’s easy to understand, then, how Leonard Cohen can enjoy playing roles in which he ‘thinks against himself’ (all the better to affirm himself, of course). Finally, I note that there are interesting parallels to be drawn between ‘First We Take Manhattan’ and ‘The Future’. The terrorist in the first song is akin to ‘the lousy little poets trying to sound like Charlie Manson’ in the second. The terrorist as ‘lousy little poet’: that, for me, sums up what ‘First We Take Manhattan’ is about.

1 – The original citation reads: ‘One writes a novel when one does not have answers; when one has answers one writes an essay.’ Kamel Daoud, in an interview on French radio (France Inter, Le grand entretien) 28 August 2024. Translated here by Richard Jonathan.

2 – Hannah Arendt, Responsibility and Judgement (New York: Schocken Books, 2003) p. 72

3 – Ibid.

8. SAME OLD SCENE (ROXY MUSIC) | QUIET LIFE (JAPAN)

SAME OLD SCENE

Nothing lasts forever

Of that I’m sure

Now you’ve made an offer

I’ll take some more

Young loving may be

Oh so mean

Will I still survive

The same old scene?

In our lighter moments

Precious few

It’s all that heavy weather

We’re going through

When I turn the corner

I can’t believe

It’s still that same old movie

That’s haunting me

Young loving may be

Oh so mean

Trying to revive

The same old scene

Young loving may be

So extreme

Maybe we should try

The same old scene

QUIET LIFE

Boys, now the times are changing

The going could get rough

Boys, would that ever cross your mind?

Boys, are you contemplating moving out somewhere?

Boys, will you ever find the time?

Here we are stranded

Somehow it seems the same

Beware, here comes the quiet life again

Boys, now the country’s only miles away from here

Boys, do you recognize the signs?

Boys, when these driving hands push against the tracks

Boys, it’s too late to wonder why

Here we are stranded

Somehow it seems the same

Beware, here comes the quiet life again

Now as you turn to leave

Never looking back

Will you think of me?

If you ever, could it ever stop?

Oh, oh, ooh, the quiet life

Tommaso Fattovich, Poppy, 2022

‘SAME OLD SCENE’ & ‘QUIET LIFE’, OR IDENTITY AS FICTION

‘Same Old Scene’ (1980) and ‘Quiet Life’ (1979), besides sharing a Euro-synth/Euro-disco sound, also share a common theme, for each is inscribed in their respective songwriter’s exploration of ‘identity as fiction’. Bryan Ferry and David Sylvian were both born into working class families, Ferry in a mining district of north-east England and Sylvian in South London.1 By 1980, the persona Ferry had built was well-established: a sophisticated man of impeccable taste living a glamourous life. By 1979, David Sylvian’s image as a glam-rock copycat was morphing into that of leader of the ‘New Romantics’. Where Ferry has assiduously constructed and maintained his persona to this day, Sylvian, who had been opportunistically improvising his, refused the ascription of ‘leader of the New Romantics’, made a final album with Japan, then embarked on a solo career in which he resolutely refused to construct any sort of persona. If ‘being himself’ ends up being his image, so be it, he seems to have said to himself, but his image is not his concern. I will now consider these contrasting trajectories, these divergent explorations of ‘identity as fiction’, in light of ‘Same Old Scene’ and ‘Quiet Life’.

1 – See David Buckley, The Thrill of It All: The Story of Bryan Ferry and Roxy Music (London: André Deutsch, 2004) and Martin Power, David Sylvian: The Last Romantic (London: Omnibus Press, 2012).

Tommaso Fattovich, Surf Solar, 2022

‘It depicts a nocturnal existence devoted to non-stop clubbing and younger partners as a deadening vacuum’. So wrote Jonathan Rigby of ‘Same Old Scene’.1 And indeed, that is what the song ‘is about’. The protagonist is a dandy, and dandies struggle to age gracefully—think of Dorian Gray—and in this respect the songwriter is depicting a character true to his own persona. ‘Young loving’ is ‘mean’ and ‘extreme’: indeed, a woman screwing a man who could be her father is bound to be conflicted, and women being ‘mean and extreme’ is simply their default mode of passive aggression. Everybody knows that—except the protagonist. So he will ‘take some more’ and wonder if he will ‘survive’ the ‘heavy weather’. And when he ‘turns the corner’ he is still haunted by ‘the same old movie’. Going round in circles—repetition, futility, stuck in a rut—is the very image of ennui. Yet rather than rebel against it and do something different, the protagonist suggests trying the ‘same old scene’. Rather pathetic, wouldn’t you say? He knows ‘nothing lasts forever’, but can’t bring himself to accept it and move on.

1 – Jonathan Rigby, Roxy Music: Both Ends Burning (London: Reynolds & Hearn, 2008) p. 227

Tommaso Fattovich, Under the Bridge, 2022

In ‘Quiet Life’, Sylvian’s protagonist takes the opposite tack to Ferry’s character. It’s not ‘the same old scene’ but ‘the times are changing’. He warns his friends that ‘the going could get rough’; then, having ‘moved out somewhere’, he sings, ‘Here we are stranded / Somehow it seems the same / Beware, here comes the quiet life again’. He rebels against finding himself in the same situation as before. All in all, he is in revolt against ‘the quiet life’, against stasis and complacency, self-satisfaction and ennui. He warns his friends that ‘the country’s [the quiet life’s] only miles away from here’ and asks them if they ‘recognize the signs’ of this prospect. He argues that once they are ‘on the tracks’ to the ‘country/quite life’, it will be too late to turn back: ‘When these driving hands push against the tracks / It’s too late to wonder why’. The keyword in the song, then, is ‘beware’. The protagonist is warning his friends that they must act now—do something new, do things differently—otherwise they will end up with the ‘same old scene’ that now inspires nothing but aversion in him.

Tommaso Fattovich, Galice, 2023

We see, then, that when both Ferry and Sylvian were considered consummate dandies, one chose to remain in the scene and the other to quit it. Sylvian decided that the fusion of fashion and music with studied indifference was an artistic dead end. Ferry chose to present himself as both hip to the vacuity of ‘glamour’ and irresistibly attracted to it. Was one right and the other wrong? No. My argument holds that to others as well as to oneself, ‘identity as fiction’ is the default mode of ‘presentation of self’. There is no foreordained identity: we are all ‘experiments in being’. Some of us realize our individuality; others are content to conform. For artists, ‘identity as fiction’ is an integral part of creativity. Consider this: ‘Far from being a label one would affix on an existing social group, the word ‘artist’ is utopian and prospective. This utopian space generated by the artist in a social context is the point where his social and his imaginary selves merge in an identity forged within fiction. The artist is thus repositioning art’s function within a society that deems it ‘useless’, endowing art with an invasive role in the sense that it is not within the frame of a fiction/reality dichotomy but is rather an operational mode of consciousness that makes inroads into existing versions of the world’.1 That, in my view, is the finest description of how an artist’s mythmaking and identity-construction are ethical acts: they are means to ‘become who one is’.2 What if ‘Same Old Scene’ and ‘Quiet Life’ were but different routes to that goal? Given that both Ferry and Sylvian seem to have realized their individuality, that is a reasonable hypothesis.

1 – Elena Anastasaki, The Myth and Identity of the Romantic Artist in European Literature: A Self-Constructed Fantasy (London: Routledge Studies in Comparative Literature, Taylor & Francis, 2023) Kindle Edition

2 – Nietzsche, The Joyful Science.

9. BROWN-EYED GIRL (VAN MORISSON) | HIGHER & HIGHER (JACKIE WILSON)

BROWN-EYED GIRL

Hey where did we go, days when the rains came

Down in the hollow, playing a new game

Laughing and a running hey, hey, skipping and a jumpin’

In the misty morning fog with our hearts a thumpin’ and you

My brown-eyed girl, you my brown-eyed girl

And whatever happened to Tuesday and so slow

Going down the old mine with a transistor radio

Standing in the sunlight laughing, hiding ‘hind a rainbow’s wall

Slipping and sliding all along the waterfall with you

My brown-eyed girl, you my brown-eyed girl

Do you remember when we used to sing

Sha la la la la la la la la la la de da

Just like that

Sha la la la la la la la la la la de da, la de da

So hard to find my way, now that I’m all on my own

I saw you just the other day, my how you have grown

Cast my memory back there, Lord, sometime I’m overcome thinking ‘bout it

Making love in the green grass behind the stadium with you

My brown-eyed girl, you my brown-eyed girl

Do you remember when we used to sing

Sha la la la la la la la la la la de da

(YOUR LOVE KEEPS LIFTING ME) HIGHER & HIGHER

Your love lifting me higher

Than I’ve ever been lifted before

So keep it up, quench my desire

And I’ll be at your side for evermore

Your know your love

(your love keeps lifting me) Keep on lifting me (your love keeps lifting me)

Higher, higher and higher (lifting me higher and higher, higher)

I said your love (your love keeps lifting me)

Keep on (your love keeps lifting me)

Lifting me (your love keeps lifting me)

Higher and higher (higher and higher, higher)

Listen, now once, I was downhearted

Disappointment was my closest friend

But then you came and it soon departed

And you know he never showed his face again

That’s why your love (your love keeps lifting me)

Keep on lifting (your love keeps lifting me)

Higher, higher and higher (lifting me higher and higher, higher)

I said your love (your love keeps lifting me)

Keep on (your love keeps lifting me)

Lifting me (lifting me)

Higher and higher, alright (higher and higher, higher)

I’m so glad I’ve finally found you

Yes that one-in-a million girl

And now with my loving arms around you

Honey, I can stand up and face the world

Let me tell you, your love (your love keeps lifting me)

Keep on lifting me (your love keeps lifting me)

Higher, higher and higher (lifting me higher and higher, higher)

Tommaso Fattovich, Superpang, 2023

BROWN-EYED GIRL & HIGHER & HIGHER, OR POETRY & PROSE

‘Brown-Eyed Girl’ and ‘Higher and Higher (both from 1967) are songs of jubilation. The mode of the first is poetry, that of the second is prose. Poetry is heightened perception, a waking to wonder expressed via a rejuvenation of language. This renewal of the idiom comes about as the poet gives form to feeling. Poetry is fresh insofar as the listener or reader is called upon to recreate what the poet has created. Consider this poem: Silence, and a deeper silence, when the crickets hesitate. And this one: With Annie gone, whose eyes to compare with the morning sun? Not that I did compare, but I do compare now that she’s gone. Leonard Cohen created these poems, and they oblige the listener or reader to recreate them each time they are heard or read. Form captures feeling: imaginative perception activates it. This is what Van Morrison achieves, via words and music, in ‘Brown-Eyed Girl’. The way the song brings memory into play is as rich as anything one finds in Proust or Joyce. As for (everyday) prose, it is the mode of ready-made language, of words as dead tokens, not living metaphors. Prose tells: poetry shows. ‘Higher and Higher’, despite its versifying, is prose. It is a recycling of dead tokens that, to those who reject the jaded, drags down the jubilation. That said, musically, it is a triumph.

Tommaso Fattovich, Fiesta Forever, 2022

Giving praise is inherent in gospel music, and in shifting from the sacred to the profane, rhythm & blues put the Lover in place of the Lord as the object of praise. We see this in ‘Higher and Higher’, a perfect fusion of gospel and R & B, where the profane lyrics are a palimpsest, a surface layer barely concealing the sacred lying beneath. The ‘Song of Songs’ brought the erotic into Christianity and, 2,000 years later, passed the baton to Jackie Wilson and Al Green. The Biblical text has a poetic richness only matched, perhaps, in certain songs of Marvin Gaye. Gospel, in the mode of praise, is declamatory and incantatory; it is perfectly suited to church singing. In shifting from the religious to the secular, however, stock phrases can only get you so far. Indeed, however well Wilson’s voice surfs the music, however good his vocal performance, he cannot infuse life into the dead language. To praise a fresh lover in stale prose is to give her a bouquet of dead flowers. (Nevertheless, she’ll dance to the music, which, I repeat, is a triumph).

Tommaso Fattovich, Holograms Cascade, 2023

‘Not from the present to the past, not from perception to recollection, but in the other direction we move’:1 ‘Brown-Eyed Girl’ bears out the truth of this statement. In the song, 21-year-old Van Morrison looks back on his younger self, perhaps 15 or 16, and the things he used to do then with a girl who was his friend. Throughout the song we have a vivid sense that the past is alive in the present, that recollection is prompting perception. The singer is ‘a memory come alive’,2 the words rolling off his tongue evoking in real time the images unfurling in his mind. Indeed, the song is cinematic, its time the ‘eternal now’ of memory, dream, and desire.

Tommaso Fattovich, I Want to Learn the Piano, 2024

Today, almost sixty years after it first hit the airwaves, ‘Brown-Eyed Girl’ is as pristine as the day it was first played. The reason for this, I suggest, is that the song is profoundly poetic: unmediated by the accretions of culture, it gives free reign to ‘a memory come alive’. In so doing, it honours the genius of the child. Everything in it coheres to convey an experience that, it convinces us, has really been lived: a girl and boy revelling in life, delighting in each other’s company, discovering their sexuality. Poetic, the song proceeds entirely by ‘showing’, each line painting a shade of color on the canvas, and when the few lines of ‘telling’ come—So hard to find my way, now that I’m all on my own / I saw you just the other day, my how you have grown / Cast my memory back there, Lord, sometime I’m overcome thinking about it—they are like black and white brush strokes come to set off the colors. Finally, acknowledging the musical affinity between our two singers, I note that, as every Van Morrison fan knows, Saint Dominic’s Preview opens with a rousing rhythm and blues, ‘Jackie Wilson Said (I’m in Heaven When You Smile)’.

1 – Gilles Deleuze, Bergsonism, tr. Hugh Tomlinson & Barbara Haberjam (New York: Zone Books, 1991) p. 63

2 – Kafka: ‘I am a memory come alive’. In The Diaries of Franz Kafka, ed. Max Brod (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1964) p; 392

10. L.A. WOMAN (THE DOORS) | ‘HEROES’ (DAVID BOWIE)

L.A. WOMAN

Well, I dig a little down about an hour ago1

Took a look around me which way the wind blow

Where the little girl in a Hollywood bungalow

Are you a lucky little lady in the city of light

Or just another lost in your city of night

City of night, city of night, city of night, whoa, come on

L.A. woman, L.A. woman

L.A. woman Sunday afternoon

L.A. woman Sunday afternoon

L.A. woman Sunday afternoon

Drive through your suburbs

Into your blues, into your blues, yeah

Into your blue-blue blues

Into your blues, ohhh yeah

I see your hair is burning

Hills are filled with fire

If they say I never loved you

You know they are a liar

Drivin’ down your freeway

Midnight alleys roam

Cops in cars, the topless bars

Never saw a woman

So alone, so alone

So alone, so alone

Motel money murder madness

Change the mood from glad to sadness

Mister mojo risin’, mister mojo risin’

Mister mojo risin’, mister mojo risin’

Got to keep on risin’

Mister mojo risin’, mister mojo risin’

Mojo risin’, gotta mojo risin’

Mister mojo risin’, gotta keep on risin’

Risin’, risin’

Gone risin’, risin’

I’m gotta risin’, risin’

I gotta risin’, risin’

Well, risin’, risin’

I gotta, wooh, yeah, risin’

Woah, ohh yeah

Well, I dig a little down about an hour ago

Took a look around me which way the wind blow

Where the little girl in a Hollywood bungalow

Are you a lucky little lady in the city of light

Or just another lost in your city of night

City of night, city of night, city of night, whoa, come on

L.A. woman, L.A. woman

L.A. woman, you’re my woman

Little L.A. woman, little L.A. woman

L.A. L.A. woman woman

L.A. woman, come on

1 – This is what can be heard on the recording, the consensus of what Morrison actually sings. The published lyrics make more sense, but as listeners we acknowledge the singer’s right to garble the words as he sees fit.

HEROES

I, I will be king

And you, you will be queen

Though nothing will drive them away

We can beat them, just for one day

We can be heroes, just for one day

And you, you can be mean

And I, I’ll drink all the time

‘Cause we’re lovers, and that is a fact

Yes we’re lovers, and that is that

Though nothing will keep us together

We could steal time just for one day

We can be heroes for ever and ever

What d’you say?

I, I wish you could swim

Like the dolphins, like dolphins can swim

Though nothing, nothing will keep us together

We can beat them, for ever and ever

Oh we can be Heroes, just for one day

I, I will be king

And you, you will be queen

Though nothing will drive them away

We can be Heroes, just for one day

We can be us, just for one day

I, I can remember (I remember)

Standing, by the wall (by the wall)

And the guns, shot above our heads (over our heads)

And we kissed, as though nothing could fall (nothing could fall)

And the shame, was on the other side

Oh we can beat them, for ever and ever

Then we could be Heroes, just for one day

We can be Heroes

We can be Heroes

We can be Heroes

Just for one day

We can be Heroes

We’re nothing, and nothing will help us

Maybe we’re lying, then you better not stay

But we could be safer, just for one day

Tommaso Fattovich, Making Plans for Nigel, 2022

‘L.A. WOMAN’ & “HEROES”, OR A TALE OF TWO CITIES (MEN, ARTISTS, SONGS)

Southern California, which is shaped somewhat like a coffin, is a giant sanatorium with flowers where people come to be cured of life itself in whatever way. This is the last stop before the sun gives up and sinks into the black, black ocean, and night—usually starless here—comes down. Along the coast, beaches stretch indifferently. You can rot here without feeling it.

John Rechy, City of Night (London: Serpent’s Tail, 2021 [1963]) pp. 109-110

The world of Lonely-Outcast America squeezed into Pershing Square, of the Cities of Terrible Night, downtown now trapped in the City of Lost Angels. And the trees hang over it all like some apathetic fate.

John Rechy, City of Night (London: Serpent’s Tail, 2021 [1963]) pp. 116

Blood stains the roofs and the palm trees of Venice

Blood in my love in the terrible summer

Bloody red sun of phantastic L.A.

Jim Morrison, ‘Peace Frog’ (Morrison Hotel, 1970)

Tommaso Fattovich, Worldwide Marine Asset Financial Analyst, 2021

In 1971, Jim Morrison left Los Angeles to begin a new life in Paris.

In 1976, David Bowie left Los Angeles to begin a new life in Berlin.

In July 1971, Morrison was found dead in the bathtub of his Paris apartment.

In January 1977, Bowie released Low and in October, ‘Heroes’.

I will now discuss ‘L.A. Woman’ (1971), Jim Morrison and Los Angeles; ‘Heroes’ (1977), David Bowie and Berlin. In each case, I will attempt to show the interplay between man, artist, city and song. My hope is that this approach will yield a fresh insight or two.

Tommaso Fattovich, Playing with a Stick of Dynamite, 2023

In a letter to rock journalist Dave Marsh in early 1971, soon after the final recording session for L.A. Woman, Jim Morrison wrote: ‘The songs have a lot to do with America and what it’s like to live these years in L.A.—and by extension—the United States. (I’ve always seen Los Angeles as a microcosm of the States, a genetic blueprint). I came here originally to make films and got into music by accident. A fortunate accident for me, as it gave me experience and an outlet for ideas. And a chance to work out a personal myth, a late-adolescent phantasy, at large. HWY, a 50-minute 35mm color film, is a further evolution of this personal heroic myth.’1 Working out ‘a personal heroic myth, a late-adolescent phantasy’, then, was something Morrison was explicitly doing in Los Angeles. Becoming a highly obnoxious alcoholic, constantly letting down his bandmates both on stage and in the studio, and finding himself incapable of renewing himself creatively was not the myth he had in mind. It is my contention that only in Los Angeles could such self-abasement have flourished. Why? Largely because Los Angeles is populated by people from elsewhere, free of the constraints of ‘home’, people free-floating and ethically ungrounded. Moreover, as Michael Sorkin says, ‘Los Angeles is a place where nothing is done by halves, a culture which exaggerates by nature, a town that gives full throat to others’ latency.’2 It is a city that is at once unreal and hyperreal. Vincent Brook puts it this way: ‘Reality has intersected with rhetoric in Los Angeles to an inordinate degree. Its history is inextricably bound to its mystification. Its inception and raison d’être emerged from a smoke-and-mirrors process both literal and figurative.’3

1 – Morisson letter to Dave Marsh

2 – Michael Sorkin, Exquisite Corpse: Writing on Buildings (London: Verso, 1991) p. 58

3 – Vincent Brook, Land of Smoke and Mirrors: A Cultural History of Los Angeles (New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2013) pp. 5-6

Tommaso Fattovich, Revival Fires, 2024

Consequently, Morrison never met anyone sufficiently grounded to tell him that Rimbaud’s ‘cultivation of the soul’1 is not compatible with the ‘softening of the brain’ induced by a bottle or two of Jack Daniel’s a day.2 To this absence of a ‘wake-up call’ from outside was added the fact that ‘inside’, Morrison never had to contend with an inhibiting superego.3 In addition, he was in the paradoxical position of being the least committed member of the Doors and at the same time their primary creative force, which meant that Manzarek, Krieger and Densmore—unlike Jagger-Richards vis-à-vis Brian Jones—were in no position to push him out of the band. As for the Doors’ fans, if Morrison had only the concert audiences to go by, they must have struck him as a bunch of kids who couldn’t tell the difference between feeling and sensation, poetry and bullshit. All in all, Morrison’s impetus to become an ‘asshole’4 found in Los Angeles the least resistance, even if other factors were involved in his self-abasement. His decision to leave the city to start anew testifies to the lucidity he never quite lost.

1 – Rimbaud, ‘Lettre du Voyant’ (Letter to Paul Demeny) 15 May 1871

2 – Of course, no matter where Morrison might have lived, he might never have met ‘anyone sufficiently grounded’ to make him rethink how he’d been living. My point is simply that in L.A. the proportion of ‘ungrounded people’ was greater than elsewhere. I recognize, however, that the people one associates with (one’s milieu) are of far greater importance than the city one lives in.

3 – Largely because in his formative years his father was frequently absent.

4 – ‘I drink so I can talk to assholes. This includes me.’ Jim Morrison, Wilderness Volume I (NY: Vintage Books, 1989) p. 207

Tommaso Fattovich, Wimbledon, 2023

There is another side to this coin, of course, and that is the work the Doors produced in Los Angeles, of which ‘L.A. Woman’ is a magnificent example. In it, form and feeling are one, as the man, smoke curling in his mind, breathes in and blows out now the city, now the woman, now the fusion of the two. In one and the same breath, as it were, he evokes his arrival in the city and his pending departure from it (in this interpretation, ‘mister mojo risin’’ = ‘Jim Morrison [is leaving]’). In the ‘city of light’ we find the ‘lucky little lady’, the ‘Hollywood bungalow’, and the ‘suburbs’, the ‘Sunday afternoon’ and the ‘blues’. In the ‘city of night’, the ‘lost angel’, the ‘midnight alleys’, the ‘cops in cars’, the ‘topless bars’ and the ‘woman so alone’. Like intermingling plumes of smoke, the two cities are inseparable. The man celebrates the duality of city/woman as, ‘driving down your freeway’, he sees ‘your hair is burning’ and the ‘hills are filled with fire’. He declares his love for this incarnation of Los Angeles: ‘If they say I never loved you, you know they are a liar’. He then evokes ‘motel money murder madness’ and changes the mood ‘from glad to sadness’. Finally, concluding the farewell ceremony to the city he is about to forsake, he becomes one with the music as it regains its ecstatic pulsation.

Jim Morrison, ‘Wasted Nights & Wasted Years’, Wilderness I

David Bowie lived part of 1975 in Los Angeles, where he made Station to Station (late September-November) and took a detour (July-September) to New Mexico to play the lead in The Man Who Fell to Earth. Bowie: ‘I’m vulnerable to suggestion by environment, and environment and circumstances affect my writing tremendously. I began to realise that the environment of Los Angeles, of America, was detrimental to my writing and my work. I realised that that was why I was feeling so claustrophobic and cut off. I wrote ‘Word on a Wing’ when I had established my own environment with my own people. I felt at peace with the world. I wrote the whole thing as a hymn. I’m starting over again in a way. ‘Station to Station’ carries a sense of optimism and celebration. There’s a certain maturity now. You can hear it in the album.’1 While still in Los Angeles, then, David Bowie was leaving it, turning his thoughts to Europe. From 2 February to 26 March 1976 the Station to Station tour played the USA and Canada, and from 7 April to 18 May, Europe. Shortly after the last date in Paris, Bowie moved to Berlin. So we see that both David Bowie and Jim Morrison understood that to renew themselves they had to leave Los Angeles, and both departed right after having made albums that have become classics. Both men had fallen very low in their personal lives, and both exercised their lucidity and courage to act on their understanding that they needed a new start, a ‘new career in a new town’. Bowie succeeded; Morrison died. I’m convinced, had Morrison lived, he would, like Bowie, have ‘started over’ and accomplished much.

1 – David Bowie interviewed by Robert Hilburn, Melody Maker, 28 February 1976. Reproduced in Sean Egan, Bowie on Bowie: Interviews and Encounters (London: Profile Books, 2015) Kindle Edition. Edited here for concision.

Tommaso Fattovich, Giraffe, 2023

David Bowie’s ‘Heroes’ (1977) and Andrzej Zulawski’s Possession (1981) are the supreme exemplars of the spirit of Berlin in the late seventies and early eighties. Like Zulawski’s film, Bowie’s song is transcendent, in that feeling and form, like wind and hawk, have become so perfectly one that the particular becomes universal.

Lavender’s blue, dilly dilly, lavender’s green

When I am king, dilly dilly, you shall be queen

Call up your men, dilly dilly, set them to work

Some with a rake, dilly dilly, some with a fork

Some to make hay, dilly dilly, some to thresh corn

Whilst you and I, dilly dilly, keep ourselves warm

The majesty of ‘Heroes’ derives first and foremost from its glorious music, but its lyrics, too, account for the song’s status as a classic. Indeed, touched by genius, Bowie opposed insidious oppression with a nursery-rhyme lyric, geopolitics with a suburban scene, totalitarian control with an episode of individual freedom, conformity with defiance, ideology with love, and dystopia with utopia. Free of facile sloganeering and self-righteous posturing, ‘Heroes’ leaves in the dust all ‘political’ songs of that stripe.

Tommaso Fattovich, Vibrrrrr, 2023

The perimeter of West Berlin, marked by the Wall, had an astringent quality, a grimness that accounts for the frugality of ‘Heroes’, its simple, stark poetry. It is a song both for Berlin and of Berlin. David Bowie, having made both Station to Station and Low just prior to making ‘Heroes’, had purged himself of the ‘poison’ of Los Angeles and so was fully alive, receptive to the ethos of Berlin. Jim Morrison: ‘Americans are TV-hypnotized. TV is the invisible protective shield against bare reality. Twentieth-century culture’s disease is the inability to feel any reality. People cluster to TV, soap operas, movies, theater, pop idols, and they have wild emotions over symbols. But in the reality of their own lives, they’re emotionally dead.’1 We note, for both Morrison and Bowie, the deadening effect of the most glamourous city in the world, and, for Bowie, the enlivening effect of one of the least glamourous (East Berlin). Paradoxes such as this are characteristic of the artist, whose experience of the world is phenomenological, not ideological; singular, not social. David Bowie and Jim Morrison, then, had far more in common than appearances would have us believe, as I hope this comparative approach has shown, and the same goes for ‘Heroes’ and ‘L.A. Woman’.

1 – Jim Morrison quoted in Lizze James, ‘Jim Morrison: Ten Years Gone’ (Creem magazine, 1981). Reproduced in Dylan Jones, Mr Mojo: A Biography of Jim Morrison (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015 [1991]) p. 35.

Tommaso Fattovich, Winter, 2024

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2024 | All rights reserved

Comments